Link to an article by Joe Pinsker:

Month: March 2015

Nick Hanauer – Stock Buybacks Are Killing the American Economy

Link to an article by Nick Hanauer:

“Stock Buybacks Are Killing the American Economy”

Bonus link: “Billionaire Hanauer Hammers Stock Buybacks”

Andrei Platonov – The Foundation Pit

Андре́й Плато́нов [Andreĭ Platonov] – Котлован [The Foundation Pit] (Pushkin House, 1987)

Platonov (born Andreĭ Platonovich Klimentov) has been hailed as one of the greatest writers of the 20th Century — an accolade not widely recognized, in part due to censorship and also its unavailability in many Western languages until more recently. He is grouped with Kafka and Beckett. McKenzie Wark has called The Foundation Pit “a critique of the Soviet project in its own rhetorical terms.” But Platonov’s work was mostly suppressed during his lifetime, with The Foundation Pit completed in 1930 but published only during the glasnost period in 1987, more than 35 years after his death. As described in the notes accompanying an English translation, Josef Stalin even wrote in the word “scum” in the margin of a copy of Platonov’s story “For Future Use.” Yet his writing survives and his recognition as a prose writer continues to grow. It also bears mentioning that after his censorship he did continue to write, often anonymously, and for that reason his writings for textbooks in the Soviet Union might even be considered widely read, in their own way.

The basic premise of the novel is the digging of — literally — a foundation pit, for the construction of a great house of the proletariat. The story unfolds with the workers on site, and in their dormitory, as well as state bureaucrats and other assorted passers-by. They dig and dig, yet no structure ever materializes in the pit. The pit just grows wider and deeper. The novel features nearly picaresque episodes, as the foundation pit provides no resolution or overall story arc (though it perhaps feigns to do so at the start).

Much like Samuel Beckett, or even Alejandro Jodorowsky, Platonov depicts strange symbolic characters and scenes but totally devoid of sentimentality or awe. In The Foundation Pit, some of the most memorable examples include the Bear, an anthropomorphic “hammerer”, and a caravan of coffins dragged away from the foundation pit worksite. These are ironic, satiric, and often metonyms. But unlike Beckett at least, Platonov is specific to his time, which is to say his writing speaks of a particular context.

Another writer who should perhaps be compared to Platonov more closely is William S. Burroughs. Each played with the language of dominant cultures, in a way sensitive to context, but tried to snip apart the knots that bound audiences to those cultures in a kind of stasis. For Burroughs, this appeared (literally) in his “cut-up” writing technique, in which he clipped passages from newspapers and other sources, and rearranged them to form new text, the “random” rearrangement seeking meaning outside the context that brought forth the words in their original form. Platonov used the slogans and symbols of the Soviet government, misappropriated to new ends. This is not unlike the bastardized pop culture anthropology of the contemporary musician Ariel Pink. Obviously, the techniques here vary considerably. Yet there is a revolutionary impulse common to them all.

People who deal with searching electronic databases sometimes suggest a “drunk walk” as a first stage of the process, in which the researcher stumbles about aimlessly gathering preliminary information before returning to the beginning and starting the “real” search, now armed with information from the “drunk walk” about how the desired information is actually structured in the database. This bears some resemblance to the ways teachers suggest grading papers, by first reading a small sample to gain an orientation of the level of performance of a class, and by reading part of a given paper before going back to the beginning and marking it for grading (and teaching) purposes. This is a process-oriented approach. The only abiding assumption is that the first steps will not succeed.

These concepts are found in their own unique forms in Platonov’s novel. He writes from a perspective that communism is something that everyone (even animals and the environment) desire, but details the flaws in understanding those desires and concomitant mistakes of actualization under dualistic bureaucratic managerialism (Slavoj Žižek in Living in the End Times calls it the “Gnostic-materialist utopia” period of the late 1920s) — a rigid discipline imposed to abandon the “wrong” ways of the past and instead adopt unequivocally “proper” collectivization. But what is unique about Platonov, unlike, say, the pessimistic essentialism found in the anti-revolutionary social democrat George Orwell‘s Animal Farm, is that it is possible to see in Platonov the failures and limitations of collectivization as part of kind of a “drunk walk”, a merely preliminary period of fruitless experimentation. It was a period of orienting to what was not recognized as the real character of the project at the outset, before the assumptions and presuppositions have been unpacked. Where Platonov elevates his work, though, is his refusal to consider his topic in terms of right or wrong, but rather suggests that even in the right and good choices there are elements of wrong or bad. Everything is muddled. There is no transcendence, no hidden golden path waiting to be discovered, and the very possibility of such things is rejected from the outset. Yet, at the same time, he suggests a kind of redemption of the past, unlocking communist desires inscribed on everyday circumstances already, rather than seeking to build them up in an uncertain future premised on opposition to the past. This is Platonov’s most revolutionary aspect. Orwell implies that people are terrible and revolutionary communism suffers from the same failings as capitalism, so why not just stick with a liberal democratic path towards social democracy and keep working toward a different political economy? The fact that even the CIA saw Animal Farm as useful for propaganda purposes suggests what little practical threat Orwell’s vision posed to the vested interests of capitalism. Platonov questions the very basis of what a real revolutionary outlook requires for success, applying every later failure as an opportunity for a continuous engagement with these questions, now robbed of any sort of finality. The so very socialist concept of dialectics the only uncertain, unsteady constant.

A recurring theme is the balance between the individual and the collective. Just as one might cringe at the neoliberal capitalist order subjecting people today to the brutalities of “the market” in a way that strips away the last remnants of private life, Platonov has concern for the way harsh “utopian” collectivization leaves no room for the individual in the bureaucratic machinery. Ostensibly the main character, Vaschev, is fired from a job early on for pausing to consider the future in these terms. There is an element of psychology at work, reflecting C.G. Jung‘s descriptions of “individuation”. The individual must be sort of protected from “total collectivization” (or “the market”) in order to be able to survive that sphere with any shred of humanity.

Ernesto “Che” Guevara concluded The Motorcycle Diaries by saying:

“I knew that when the great guiding spirit cleaves humanity into two antagonistic halves, I will be with the people”

Platonov is often described as supporting “widows and orphans” and such, in the same way. That is, he sided with society’s most vulnerable. He always has special concern for the weak, the powerless and the downtrodden. But mostly he recognized what could be found among ordinary people. So he shines a gleaming light on Nastya, the orphan cared for by the workers, and even the cantankerous Zhachev, the disabled veteran called “comrade cripple” at one point. Platonov subtly critiques the ploys to create or recreate power structures in the newly collectivized Soviet Union that eerily resemble imperial Russia, revealing how collectivization was changing society by reorganizing the control of means of production only to retain certain hierarchies of power, much like many of the great sociologists that came along in the same century described (including even Thorstein Veblen, to the extent his work had a sociological character). The historian Moshe Lewin has even described the Stalinist era of the Soviet Union as a despotic return to the values of the tsarist autocracy. But, again, unlike Orwell, Platonov does not seem to suggest that any such actions are inevitable, but rather, that the original communist vision in its “drunk walk” merely failed to account for those possibilities sufficiently. There were presuppositions in the Soviet five-year plans that produced unwanted and unintended consequences. In “On the First Socialist Tragedy” (1934), Platonov concluded, “It is necessary to stand in the ranks of the ordinary people doing patient socialist work — that is all we can do.”

In the Soviet Union, kulaks (rich peasants) were “liquidated” to eliminate them as an economic class. In Platonov’s novel, in a play on words typical of the novel, this means quite literally sending them down river on a raft! But here, we also encounter a kulak mending a bast sandal (a type of woven footwear known for its cheapness and lack of durability, and associated with poverty), which alludes to attempts by the Soviet regime to designate “sub-kulaks” and shade off the original “utopian” duality of peasants as kulaks (rich) or non-kulaks (poor) into a mire that undermines the original intent. So maybe most remarkably, Platonov tends to not denounce kulaks, or other characters that hide their past connections to privilege in order to avoid liquidation, and instead focuses on siding with the ordinary person. One of the most likeable (and unique) features of his writing is that it welcomes anyone willing to commit to the communist endeavor — anyone willing to promote equality from the standpoint of the ordinary person.

The Foundation Pit was translated to English twice by Robert Chandler, who has noted that the second (in 2009 for NYRB Classics, with Elizabeth Chandler) contains a more definitive Russian source text and is informed by intervening Platonov scholarship. Because of Platonov’s fondness for puns, Chandler’s efforts to capture those elements as faithfully in translation are laudable (even if this reviewer is in no position to judge his success in that regard).

The Most Dangerous Woman in America

Link to an article on Kshama Sawant by Chris Hedges:

Pankaj Mehta – Big Data’s Radical Potential

Link to an article by Pankaj Mehta:

John Cale – Vintage Violence

John Cale – Vintage Violence Columbia CS 1037 (1970)

John Cale’s solo debut is shocking. One might have expected some all-out avant-rock akin to what Cale did with The Velvet Underground. Maybe some droning classical compositions like he had recorded with Tony Conrad (later released on the “New York in the 60s” series). Or maybe even something like the albums he produced for The Stooges and Nico. Instead he delivered a Bee Gees Odessa, a Beach Boys Sunflower, or something along those lines at least.

Cale wrote songs with a vast awareness of what he was capable of. Vintage Violence casts the arty ambitions aside and works from scratch. He conceived and recorded the whole album within about two weeks. What surfaces is a delicate naiveté. The songs are nostalgic. Every word seems to reference a fond, or at least strong, memory.

Rock and roll was a somewhat spontaneous endeavor for John Cale. He had classical training and just fell into to rock and roll with The Primitives (Lou Reed’s fabricated touring outfit that became The Velvet Underground). So he arrived with an articulate, fully-formed identity. But then he fell in love with the whole rock and roll thing. Cale made his rebellion with The Velvets. For his solo debut, he dove into pop music. He was willing to try anything it seems. Yet, he was already enough of a master to anticipate the consequences of every move. There may be sudden shifts and shimmies, but Cale responds to each with careful follow-throughs.

Recording his debut, Cale was still married to fashion designer Betsey Johnson (who was responsible for dressing up The Velvet Underground in their day). Lots of things could be said about that influencing the lush, sophisticated pop of Vintage Violence. You could stack a hundred Neil Diamond albums on top of each other and not have the elegance of John Cale’s compositional grace with pop songs (“Big White Cloud” is worthy of a great Scott Walker song). Certainly something changed by the time Cale was recording abrasive albums like Sabotage/Live and Honoi Soit.

At times the lyrics fall on their face, but anyone who expects otherwise would be the type who would have run into Andy Warhol and expected an engaging conversation (ha!). Then again, songs like “Amsterdam” and “Charlemagne” would make Cale out to be a great lyricist.

Vintage Violence cast no shadow on future projects. Church of Anthrax recorded around the same time with Terry Riley bears no resemblance. This wasn’t the last time Cale dove headfirst into pop music though.

Maybe Vintage Violence works because it throws a brick through the window of the avant-garde. The people inside were so busy throwing their own bricks that maybe this inadvertently got thrown back out.

John Cale – Paris 1919

John Cale – Paris 1919 Reprise K 44239 (1973)

Few albums defy categorization like Paris 1919. Though not popular at its original release, it is an album extensively referenced by critics and is a captivating work appreciated best upon extended reflection.

Is it pop? Is it classical? Is it experimental rock? Maybe it is country or blues? Don’t they call this guy a “godfather of punk”? Categorizing John Cale is as productive and interesting as staring upward and counting holes in ceiling tiles. He made his own way. Few have attempted such sweeping musical portraits of home and history that shape a life.

Paris 1919 is a personal album for Cale. It reflects himself, rather than the racy crowd he ran with. Cale focuses on fond memories. He envisions a future built on the distilled successes of his past or at least the most profound questions that passed his way. This makes the album more endearing than the equally brilliant Fear. Paris 1919 takes the sophisticated pop of his solo debut, Vintage Violence, to a higher level by replacing naïve (in a good way) exuberance with calm confidence. Exposing anything personal makes an artist vulnerable, but truly great art requires some kind of revelation. Even metaphysical statements must usually come with a personal attachment. Cale achieves this in every respect.

Cale could expertly handle the sometimes-tedious task of composing new works. The results can be deceptive. A casual listen may suggest this is a straightforward album. Closer inspection reveals his placement of pulsing vamps, sharp dissonances, and sonic swells. These techniques are merely a means to realize his vision, as the lighthearted joys of the material always supplant technical considerations. The album is not an assemblage of independent components. Instead, Paris 1919 works as a unified whole always trained on the basic principles Cale held most dear.

Though not particularly known for his lyrics, Paris 1919 holds some of his best. He even includes reference to fellow Welshman Dylan Thomas. Cale’s greatest success is in making music uniquely his own. This isn’t a performance-heavy album for him. Most of his efforts lie in guiding his vision. Against Cale’s Welsh lilt the studio band sparkles, featuring Little Feat members Lowell George and Richard Hayward.

Despite difficulty in comparison, Paris 1919 is a unique artistic triumph. A work like this rarely fits into the preconceived notions of pop culture since it goes beyond what once seemed to be the outer limits. Paris 1919 is uplifting and intimate without heavy-handed sentimentality.

Hunter S. Thompson – A Southern City With Northern Problems

Link to a 1963 article by Hunter S. Thompson:

“A Southern City With Northern Problems”

Bonus link: “Civil Rights Activist Carl Braden Convicted of Sedition”

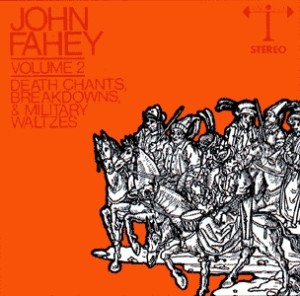

John Fahey – Vol. II: Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes

John Fahey – Vol. II: Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes Takoma C-1003 (1963; 1967)

A good choice for an introduction to John Fahey. He recorded two versions of the album, which features songs on the more straightforward side of his repertoire when he was still expressing things that fall more or less within the realm of the traditional musics from which the underlying stylistic elements originate. A 1998 CD collection presents the two different versions of Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes. Fahey’s technique on the 1967 re-recording of the original album is far crisper, and the recording quality is imminently superior so you hear everything in greater detail. The second time around he managed to improve on some songs in the relatively weak middle section of the original 1963 album (“On the Beach at Waikiki”, “Spanish Dance”, “John Henry Variations” and “Take a Look at That Baby”). Then again, his performances of “Some Summer Day” and “When Springtime Comes Again” are arguably superior on the original version, and the different versions of the album didn’t include all the same songs, so it’s nice to have both complete versions of the album collected on one CD. If you find yourself drawn to some of the more unusual elements detectable in each song, then proceed to Fahey’s more challenging stuff like Volume 6: Days Have Gone By and The Voice of the Turtle. If you simply like the impressive guitar technique and the nice songwriting, then try other Fahey releases like The Transfiguration of Blind Joe Death and Vol 3 Dance of Death & Other Plantation Favorites or something from Fahey acolytes like Leo Kottke.

Robin Marie Averbeck on Liberalism

Links to articles by Robin Marie Averbeck on Liberalism:

Bonus Links: Carl Schmitt (“The essence of liberalism is negotiation, a cautious half measure, in the hope that the definitive dispute, the decisive bloody battle, can be transformed into a parliamentary debate and permit the decision to be suspended forever in an everlasting discussion.”); “NewLiberalSpeak”; and “The Ghosts of Obama’s Victims: Liberals’ Attacks on Cornel West Expose Their Political Bankruptcy”