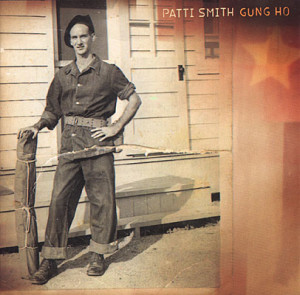

Patti Smith – Gung Ho Arista 07822-14618-2 (2000)

Playwright Bertolt Brecht wrote an essay “Writing the Truth: Five Difficulties” (revised April 1935) in which he established that “anyone who wishes to combat lies and ignorance and to write the truth must overcome at least five difficulties. He must have the courage to write the truth when truth is everywhere opposed; the keenness to recognize it, although everywhere it is concealed; the skill to manipulate it as a weapon; the judgment to select those in whose hands it will be effective; and the cunning to spread the truth to such persons.” He noted that these challenges are formidable even “in countries where civil liberty prevails.”

Courage Patti Smith has a certain amount of courage. Returning from retirement in the 1980s, she has had to battle detractors who claim nothing matches her brilliant 1970s output. She also has to fight the easy option of simply retiring again, and not thrusting herself into the spotlight. But there is more at play than just personal concerns. Gung Ho is political. Yet this is a kind of politics that is dangerous for those few and powerful who thrive on the suppression and obfuscation of the truth. Just putting music like this forward requires taking a few arrows, no matter what reputation Patti has in punk circles.

Keenness The young often lack the perspective to adopt a workable political position. The old often lack the tenacity and conviction to stick with what they know to be right, having caved in or lost sight of it along the way. Patti Smith has somehow managed to cut through the problems of both the young and old. She deals with both abstract and general issues on the one hand, and current and topical ones on the other hand too. Her music has a depth of knowledge behind it that sets it apart. That aspect should not be ignored. Herman and Chomsky’s Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988), built on Bernays’ Propaganda (1928) but drawing opposite judgments, establishes that even in a society of a “free press” there is a pervasive distortion of the historical record and an avoidance of certain topics inconvenient to the powerful. While it can be said her heart is in the right place, it can also be said that she is informed enough to avoid the common pitfalls of a leftist outlook—and make no mistake that hers is a leftist outlook.

Skill Patti Smith can still write a good song. Her skill with words is largely undiminished from those days when she first became known as one of rock’s greatest and most iconoclastic lyricists. With respect to writing music, her choices seem somewhat tempered. There is something of an edge lacking here, with a pervasive feeling that she is working only with stock forms. Little about the music links it to the specific content of the lyrics. Though at times, as with “Lo and Beholden,” the music rises to the words admirably.

Judgment Patti Smith is preaching to the choir. Her “comeback” albums (starting with 1988’s Dream of Life) have appealed primarily to an existing fan base. Politics were always an inherent part of Patti Smith’s music, but she rarely invested so much space to it on an album as here. It may still be too early to tell if Patti had the judgment to reveal enough to the right people. The meaning is there if one cares to look. Her fans were probably the best bet. Maybe they are most likely to open up the album booklet and see Patti’s photos of Ho Chi Minh’s jacket and typewriter—those small, seemingly insignificant items of a man who lead his impoverished, powerless people to victory over the most powerful and cruel military force on the planet—and seek the meaning behind them. And on the topic of Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam, why not look further toward the economic changes since the victory—any sweatshops to be found?

Cunning There was radio play for Gung Ho, as much as could be expected. Fans knew about this album. The question remains though whether the middle ground this album inhabits places the power of its words in the right hands. It may use boilerplate rock forms that have a certain generic appeal, but they are ones that don’t seem to intrigue her fans all that much, considering so many of those fans lament the lack of harder, more classically “punk” sounds. On the other hand, new listeners probably probably wouldn’t gravitate to this as it just doesn’t sound contemporary and faddish. Yet there was a mainstream rock award nomination for “Glitter in Their Eyes.” Cunning, perhaps, is the stumbling block. For it is not as if Patti lives in a society that is not civil, or one that bans music. But navigating the realms of media empires and marketing bluster is no small task. Can the message remain in spite of unspoken censorship and plain neglect? The real test, in time, will be whether Gung Ho passed this final hurdle. It certainly weighs in the album’s favor that it is aimed at the general population. Even if Patti’s style is very literary and sophisticated, her music is not like some essay in an academic journal read by practically no one. And Patti isn’t exactly trying to vest the power in herself alone. Maybe she is familiar with Piven and Cloward’s books like Poor People’s Movements: Why They Succeed, How They Fail (1977) and Why Americans Don’t Vote: And Why Politicians Want it That Way (1988).