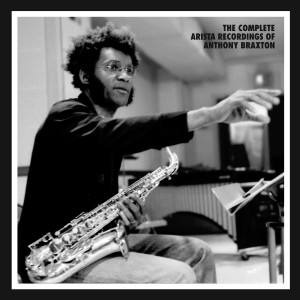

Anthony Braxton – Five Pieces 1975 Arista AL 4064 (1975)

Anthony Braxton has to be one of the last jazz musicians to achieve “giant” status before the genre’s popularity declined to the point where doing so became an impossibility. It has been noted that when he was the first jazz signing to the new major label Arista, he promised to be some kind of crossover success (see the liner notes to The Complete Arista Recordings of Anthony Braxton and a November 2008 essay in The Wire magazine discussing its release). Well, success he certainly did achieve. Despite the widely-held belief that new jazz was no longer profitable for labels or musicians from the mid-1970s onward, Braxton’s series of albums for Arista all sold relatively well–enough for the label to break even even if Braxton himself never financially profited. In terms of being a “crossover” artist, that is a bit more difficult to assess. Leading up to his tenure with Arista, he had recorded works like For Alto that extended into the territory of modern composition (of the likes of John Cage), but he also worked with more traditional jazz material on albums like In the Tradition. And that has remained his mode of operation since–drifting back and forth between the twin poles of traditional jazz and avant-garde composition. But does that constitute a “crossover”? It would seem most of the time the answer is no. But Five Pieces 1975 and some other Arista recordings do make strides at crossing the divide between traditional jazz and modern composition, achieving a new synthesis of both within a given piece. It seems for that reason it manages to be one of his best efforts.

The success of Five Pieces 1975 certainly has a lot to do with the superb band surrounding Braxton. They are up to the challenge of each piece and every performer is a match for the next. There is a balance achieved between them that evidences a complete mastery of both the compositional elements and the more liberal improvisational sensibilities at work. If the album could be improved, it would be to replace “You Stepped Out of a Dream” with something like “Opus 40P” or even “Maple Leaf Rag” from Duets 1976 to add more variety. But then again, why tamper.

Musicians labeled “prolific” are usually also saddled with the label “inconsistent”, if nothing else due to the almost inherent lack of editorial decisions to provide some kind of focus. Anthony Braxton is saddled with both those labels, as well as the one calling his music “difficult”. Yet through the years he’s also managed to do some things the “jazz-industrial complex” (his term, like the military-industrial complex and prison-industrial complex) doesn’t normally allow. Thanks largely to a source of income teaching in later years, he has managed to keep writing and recording challenging works without giving up on his mellower, more lyrical and accessible impulses. He has also managed to come about as close to being a household name as any modern jazz musician since Coltrane’s era (apart from certain members of the Marsalis family and a few pop musicians masquerading as jazz artists). So aside from his purely musical contributions, which are indeed numerous, he has presented an image of jazz that contrasts with the accepted one. That may be his most enduring achievement. It means that there will be more than one path forward.