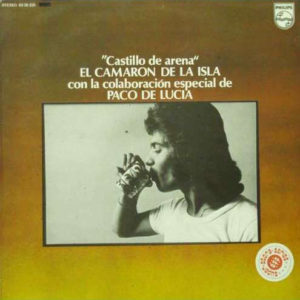

El Camarón de la Isla con la colaboración especial de Paco de Lucía – Castillo de arena Philips 63 28 255 (1977)

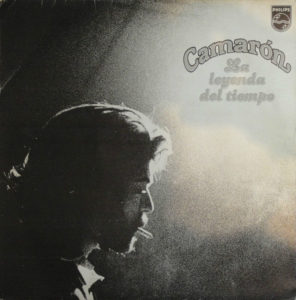

Castillo de arena (translation: “Sandcastle”) was the culmination of years of collaboration between noted flamenco performers Camarón de la Isla (vocals) and Paco de Lucía (guitar). Camarón is strongly associated with raising the prominence of flamenco music among international audiences. Both performers also helped develop what is called “nuevo flamenco,” which incorporated elements of non-flamenco music. While Camarón’s next album, the pathbreaking La leyenda del tiempo, is most strongly associated with a transition to nuevo flamenco, there are subtler gestures in that direction already present here. And, anyway, to insist on flamenco purism is a bit ridiculous anyway, given the already syncretic nature of the music. It shares aspects of a variety of ancient musics, including — in brief segments, especially in the vocal phrasing — some striking resemblances to Moroccan berber music (and specifically Jbala sufi trance music) from the likes of The Master Musicians of Joujouka/Jajouka, which, after all, comes from merely a few hundred kilometers away to the south across the Straight of Gibraltar.

Brook Zern has said,

“He was known for afinacion, which means the ability to be perfectly on pitch but not necessarily on the notes of a Western scale. Flamenco music uses microtonal intervals all the time, and nobody cut them closer and did them more precisely technically than this young artist.”

Camarón was Romani (gypsy) by birth. He definitely imbues in his music the defiant character of his upbringing in a (notoriously) dominated social group, evidenced by his willingness to break from tradition and use of afinacion. His voice is husky, almost sandpaper coarse, yet precisely pitched and expertly controlled. Paco de Lucía complements the singing perfectly, with intricate strumming and embellished melodic lines that flow back and forth smoothly and seamlessly. Flamenco style guitar playing really represents one of the most interesting ways of strumming a guitar, with far more rhythmic (not to mention melodic/harmonic) intricacy than the often lazy manner of strumming chords on a guitar in many Western traditions that hardly do more than establish a chord progression.

Like much flamenco music, this album has a melancholic and bitter yet emotionally fiery feeling. “Y mira que mira y mira” and “Como castillo de arena” have the most modern “nuevo flamenco” elements, with a vocal chorus on the former and layered, almost mechanical (motorik?) handclaps on the latter.

Flamenco music, in general, has been described this way:

“A typical flamenco recital with voice and guitar accompaniment, comprises a series of pieces (not exactly “songs”) in different palos [styles]. Each song of a set of verses (called copla, tercio, or letras), which are punctuated by guitar interludes called falsetas. The guitarist also provides a short introduction which sets the tonality, compás and tempo of the cante.”

Castillo de arena definitely follows the format of such a traditional flamenco recital, lacking only a traditional dancer.

This is another excellent effort by some of flamenco’s more highly regarded performers on the 20th Century. Although in some ways the experimentation of La leyenda del tiempo is more intriguing, those not ready or interested in synthesizers and electric instruments in flamenco often cite Castillo de arena as these performers’ best recording. There is certainly no need to pick a favorite, as both are excellent and come from a peak period in the careers of both Camarón and Lucía.