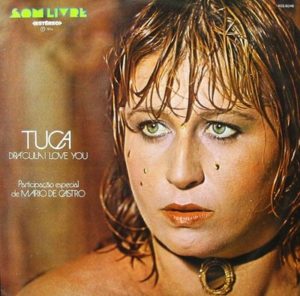

Tuca – Drácula I Love You Som Livre 403.6046 (1974)

The Brazilian musician Tuca (born Valeniza Zagni da Silva) was an enigmatic figure, these days relatively unknown. If at all, she is recognized for her collaborative work writing songs for and playing guitar on Françoise Hardy‘s La question and playing guitar on Nara Leão‘s Dez anos depois (both from 1971). There is little biographical information about her readily available in English. However, Françoise Hardy’s memoir Le désespoir des singes et autres bagatelles recalls how Tuca lived in France in the early 1970s, then, after returning to Brazil, died at age 34 due to complications from an aggressive weight-loss program. Hardy also noted that Tuca (a lesbian) was infatuated with the Italian actress Lea Massari, who was heterosexual and not interested. Tuca also had some type of physical ailment that caused body odor (trimethylaminuria? fistula? diabetes? an overactive thyroid?), leading to self-consciousness. These currents of personal ambition, hope, self-doubt and disappointment contextualize what Tuca’s music was about on Drácula I Love You, her third and final full-length album.

The album was recorded outside Paris at the iconic Château d’Hérouville studio, where a host of well-known Western pop/rock artists made recordings in the early 1970s. The music is pop, in a way. Yet it does not fit neatly into any genre categories though. It draws from the mainstream to more skewed avante-garde rock, melding aspects of Brazilian music — Erasmo Carlos‘ Carlos, Erasmo… and Rita Lee‘s Build Up make somewhat decent reference points — to French chanson and prog rock. The album’s personnel included co-producer Mario de Castro, plus François Cahen (of Magma) on horn arrangements and Christian Chevallier on string arrangements. It oddly relies on a lot of acoustic guitar, with sequencing that shifts between spare acoustic passages and elaborately orchestrated ones. There are occasional electronic effects. Tuca’s vocals are very androgynous. She often sings in a lower register than most female singers.

The tone of the album is often despairing and melancholic — recalling La question and Dez anos depois. But, equally, this has glitzy horns like much Brazilian pop music of the the time. This is also weird personal stuff, the sort of thing found on lo-fi “bedroom” recordings. And there are some strange parallels to The Rocky Horror Show (which was on stage in London the prior year) too, especially the way the album cover shows Tuca in what one review described as “Hammer horror-movie glam[.]” Dracula was apparently “in” for 1974. Even Harry Nilsson and Ringo Starr were exploring that theme in music and film that year too.

The strange, incongruous juxtapositions of elements and styles hint at what this album really captures so well — the struggle to balance the public and the private, the introverted and the extroverted. The album’s personality emerges in the way it can’t find any direct expression to capture what it wants to say. So, instead, there is an oscillation between coordinates that kind of surround its center, its core. Also, much like Jim O’Rourke‘s “pop” albums from decades later (Simple Songs, The Visitor, etc.), there is a kind of catharsis in the way the music comes together in spite of a conflicted, ambivalent attitude toward conventional commercial success. Tuca sings and plays guitar with a kind of punky edge, never completely at ease with the grand orchestrations that rise up again and again, persistently returning to raw, truncated guitar strumming and warbled, dispirited vocals. There are up-tempo songs with celebratory rhythms. Tuca seems unable to enjoy them. So she creates her own twisted, downer take on them. Not speaking Portuguese, the lyrics are a mystery, but the music alone conveys a lot.

A strange album that still sounds ahead of its time.