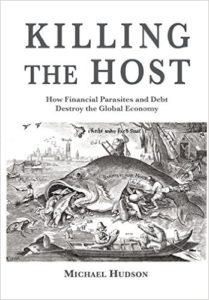

Michael Hudson – Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Destroy the Global Economy (ISLET/CounterPunch 2015)

First off, it must be said that Michael Hudson offers one of the most astute conclusions about the cause of recent financial troubles in the United States (post-2007). The crux of his book Killing the Host is to explore the coded language used to push a particular political agenda under the guise of “objective” economic theories. The most compelling sections of the book are the play-by-play histories of actions by politicians and financial technocrats. He details how a pervasive attitude of “there is no alternative” (TINA) covers up pro-banking, pro-finance, anti-labor, anti-democratic policies (this explanation mirrors Jacques Lacan‘s notion of “university discourse”). He points to others who have reached the same conclusion, and some data (albeit a minimal amount of data) that policies alleged by their backers to produce one result actually achieve another. Hudson is at his sharpest when he calls out the peddlers of these theories as frauds, and occasionally as simply “useful idiots”.

The scariest aspects of the entire narrative is how much power is concentrated in the hands of so few. It is sort of common for progressives to criticize the prospects for voting to impact progressive causes. Howard Zinn, Robert S. Borden, Jean-Paul Sartre and others have made various claims to that effect. Yet Hudson’s book gives lie to that. For example, in the most gripping sections of the book, he reveals the enormous power that President Obama and his Treasury guy Tim Geithner (plus a handful of other close operatives) wielded after the 2007-08 U.S. financial crash. The entire economy and that of generations to come was wrecked by these few actors. Wait, read that last sentence again.

Unfortunately, this ends up being the least of Hudson’s recent books. Many of the chapters are brief summaries of things Hudson has written about elsewhere. The first part of the book discussing the history of classical economics is mostly subject matter covered in his Trade, Development and Foreign Debt. He also repeats his discussions of the role of debt (and “debt deflation”) that are explained more fully in The Bubble and Beyond. Later in the book he really extends himself to the limits of economics as such, but does not venture far enough to support his normative claims, which always seem intentionally withheld. Much of Hudson’s argument is that the financial industry has concealed or obfuscated accurate information about its actions and has captured regulatory apparatuses to prevent oversight and accountability. But doesn’t that call for an analysis based in political science, or perhaps sociology? When he talks about regulatory capture, the thing is he doesn’t really provide much evidence. He could cite the work of, say, Thomas Ferguson, to explain the “right turn” in politics in the neoliberal era, or any number of other non-economic scholars. The problem for the book is that Hudson will write a chapter detailing economic issues, or perhaps histories of political dealings. Then the chapter concludes with explanations that were not explored in that chapter. That approach is repeated throughout the book. For example, chapter 9 makes the comment, “Television news shows and the printed press tend to treat debt and prospects of defaults as a downer story that loses audience interest compared to the success stories of financial celebrities.” This seems plausible, but why? It highlights the crux of the problem with this book, in that it pushes the questions of financial exploitation to essentially political decisions made outside the realm of economics as such. Hudson tends to drop one-liners to explain why journalists offer no bulwark against this, without really bothering to support those theories. Why exactly do journalists side with the financial industry rather than provide useful information for readers? People like Robert McChesney, Edward S. Herman, Noam Chomsky and John Pilger have offered theories (Pilger appropriately calls some of them “Vichy journalists”). But readers of Killing Host are left guessing as to which theory or evidence Hudson bases his conclusions on — the evidence he gathers in each chapter tends to stop well short of substantiating his broader and more interesting conclusions. So time and again the deepest questions are simply outside his scope of expertise — or rely on a kind of “preaching to the choir” attitude that presupposes that readers agree with him on the (unstated) ideological level.

In chapter 25 Hudson rails against U.S. district Judge Thomas Griesa regarding Argentina’s sovereign debt crisis. The issue is whether a minority group of bondholders of sovereign debt can be bound by an agreement of a supermajority. This is one of the low points of the book. Hudson doesn’t cite primary authority, mostly secondary sources from the financial press. This hints that he perhaps is misinterpreting the legal rulings (or relying on journalists who misinterpret the rulings). But in any event, he strongly implies a kind of sinister judicial intervention into geopolitics that is preposterous — and backed by no evidence, other than a cursory discussion of how Judge Griesa reached a conclusion he and some others disagree with. Not to defend Griesa’s ruling necessarily, but Hudson offers little more than ad hominem attacks and normative policy gripes, while feigning to be just delivering the facts.

Another example is in chapter 2, where he writes, “Thomas Aquinas (1225-74) wrote that bankers and tradesmen should earn enough to support their families in a manner appropriate for their station, including enough to give to charity and pay taxes.” (Hudson provides no cite to attribute that position to anything particular in Aquinas’ writings). Isn’t the entire question, though, what is bankers’ proper “station”? The political question at hand is that the finance sector clearly thinks its station is orders of magnitude above that of other occupations and economic sectors. Hudson thinks otherwise. But why? The answer, of course, comes from Hudson’s ideology. As much as he rails against bankers and their political allies as ideologues, Hudson is one too! Of course, his position is one that is based much more on equality and fair dealing. But he mostly takes those points as self-evident.

The piece that is largely missing from Killing the Host is the sort of stuff that sociologist Luc Boltanski has written about extensively and explicitly. And one can raise the same concerns that people have raised about Boltanski’s analysis: “Is it really possible to move beyond the particular cities and worlds to see them from without from a kind of objectivist no-where perspective as the authors try to do?” Replace “cities and worlds” with “economic doctrines” and read “authors” in the singular, and this is precisely the theoretical difficulty presented by Killing the Host. Hudson repeatedly lambasts bankers/financiers as if they are amoral frauds, but bankers and financiers don’t see themselves that way at all. The key is the way Hudson implicitly defines what constitutes public good. The problem is that we only get that moral judgment implicitly, not explicitly in his book.

Hudson has an awareness of socialist theory, but writes as if it can be applied in an analysis without an endorsement of socialist ends. One online reviewer said, “There is a leaning towards socialist values that I do not condone . . . .” It is of course irrelevant what that reviewer does or does not condone, but Prof. Hudson ultimately is preaching to the choir when he makes no real argument as to why socialist perspectives offer more than right-wing neo-feudal ones.

Consider this argument from 1919:

“Bourgeois democracy is democracy of pompous phrases, solemn words, exuberant promises and the high-sounding slogans of freedom and equality. But, in fact, it screens the non-freedom and inferiority of women, the non-freedom and inferiority of the toilers and exploited.”

That was a quote from Lenin. It is a form of the same argument Hudson makes. So is Hudson a Leninist? The introduction suggests that maybe he is. On the other hand, further into the book he alternates between talking favorably about economic policies that make nations “competitive” and criticizing disproportionate power and inequalities. This comes closer to socialist nationalism, and maybe the moderate socialism or civic nationalism of John Stuart Mill (or maybe even Alec Nove). Which is it then? He presents many of these concepts in a way that is never resolved in the book. Lenin, of course, said that there must be a global socialist revolution to achieve radical egalitarianism across borders. That is a resolution. But fostering national competitiveness like in the protectionist school of economics simply privileges some inequalities (so long as they are cross-border) over others, and ignores the threats posed by conflict between nation states. We might even start to call him the “Renegade” Hudson here, due to the ways such incongruous positions resemble those of Karl Kautsky (who turned Marx into a common liberal in Lenin’s eyes).

Furthermore, Hudson’s overarching metaphor about financial “parasites” who are “killing the host” ends up being completely incongruous with his most incisive economic critiques. Consider this dichotomy:

“for a populist, the cause of the troubles is ultimately never the system as such but the intruder who corrupted it (financial manipulators, not necessarily capitalists, and so on); not a fatal flaw inscribed into the structure as such but an element that doesn’t play its role within the structure properly. For a Marxist, on the contrary (as for a Freudian), the pathological (deviating misbehavior of some elements) is the symptom of the normal, an indicator of what is wrong in the very structure that is threatened with ‘pathological’ outbursts. For Marx, economic crises are the key to understanding the ‘normal’ functioning of capitalism; for Freud, the pathological phenomena such as hysterical outbursts provide the key to the constitution (and hidden antagonisms that sustain the functioning) of a ‘normal’ subject.” In Defense of Lost Causes (2008) (p. 279).

“let us not blame people and their attitudes: the problem is not corruption or greed, the problem is the system that pushes you to be corrupt. The solution is neither Main Street nor Wall Street, but to change the system where Main Street cannot function without Wall Street.” “Occupy Wall Street: What Is to be Done Next?”

Doesn’t Hudson offer what looks like a socialist/Marxist/Leninist critique of the overall economic system as such (capitalism), but then abandon that critique in the end to rail against the corrupting financial intruders — at most a corrupt/parasitic sub-system or isolated glitch within an otherwise sound overall system? Hudson seems like yet another writer unwilling to follow his analysis through, instead softening and undermining it to avoid appearing like an advocate of socialist/communist policies. This looks like left populism, in that “left populism’s appeal rests mainly on a moral conception of the economy — pitting producers against parasites — rather than on a radical repudiation of capitalism itself.”

In chapter 13 he provides a valuable history of the TARP bailout program following the 2007-08 financial crash. However, when discussing the government refusal to turn Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac into public companies, he says, “This was euphemized as saving the economy from ‘socialism.'” The ironic quotes are Hudson’s, and they are the crux of the problem. Wouldn’t public ownership precisely be socialism? In other words, this is no euphemism. Hudson is advocating socialist solutions to some degree, but he doesn’t want to come out and admit it. In complete contrast, take Slavoj Žižek‘s Trouble in Paradise: From the End of History to the End of Capitalism. Žižek concludes the book by saying that meaningful change will require that communism be the goal. How is that for a direct and bold statement!

So long as Hudson dodges the questions of political ideology, his arguments will seem just as ideologically limited as those of the finance sector he criticizes. Though, in fairness, he is arguing for policies that would favor a larger segment of the world’s population than the policies of neoliberalism. He tries to defend Enlightenment-era rationalism against a counter-enlightenment view that has come to dominate. Hudson takes an explicitly broader view than most economists, but not that much broader. He likes to refer to the viability of a “mixed economy”. However, the precise balance of the so-called “mixed” economy he endorses is not spelled out in any meaningful way — it is simply somewhere in the vast middle ground between the most extreme ends of a spectrum. Such vagueness is troubling.

So, while it is worth repeating that Hudson is one of the economists most worth reading today, Killing the Host is a hastily argued work with sections of profound impact and others that are scarcely more than drivel in the mold of the “academic aristocrat” tradition. A primary limitation is the book’s oscillation between theory and observation, without those two being closely matched — there is theory offered without supporting factual observations and observations that seem offered in support of theories not outlined in the book. If the book was reduced to the just the historical/journalistic sections on the chicanery of Tim Geithner and the TARP bailouts, this book would have been better. As it stands, this is kind of minor footnote at best among Hudson’s books. Read his magnificent Super Imperialism (a modern classic), or even Trade, Development and Foreign Debt (quite a bit drier) or The Bubble and Beyond (good if sloppy) instead.