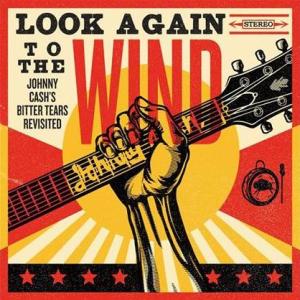

Various Artists – Look Again to the Wind: Johnny Cash’s Bitter Tears Revisited Sony Masterworks 88843 06067 2 (2014)

Johnny Cash was a guy whose greatest achievements took substantial influence from his religious beliefs and upbringing. When he spoke or performed in a way directly dealing with religion, it usually came across as overly literal, in the most absurd sort of way (The Gospel Road). “Hey Jesus, turn this water into wine real quick!” Where (christian) religion served Cash the best was in standing for the proposition of being a better person, and taking the burden for doing so upon yourself. Not, as is increasingly the case with the many sorts of egotistical flavors of religion popular today, by convincing yourself that you are a better person than others no matter what you do or by claiming to help others by helping yourself. Cash was no saint. His personal history is littered with sordid details and grave mistakes. Instead, this proposition is about acknowledging flaws and striving to make the world a better place, through acts of generosity and humility. It is the idea that no matter who you are, what you are, you can be (and do) better, measured in terms of what your own efforts accomplish for others. In this regard, Cash’s secular music that still took moral authority from religion, and gave expression to his political views that leaned toward egalitarianism, stands out. Few professional efforts in his career embody this more directly than his 1964 concept album Bitter Tears: Ballads of the American Indian. The other most apparent example was his support for prisoners, represented most visibly by his series of live albums recorded in prisons (At Folsom Prison, etc.). But before he became a leading advocate for compassionate treatment of prisoners, he made an album about the shameful treatment of Native Americans. Bitter Tears was his first use of his fame as a musician in the context of social issues.

The idea of descendants of white European settlers in the New World taking a sympathetic, moral view of the Native Americans certainly began long prior to Johnny Cash’s lifetime. Helen Hunt Jackson published A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government’s Dealings with Some of the Indian Tribes in 1881. The very title of the book alone conveyed that the European settlers treated Native Americans with without honor. As she wrote, the “lesser” right” of occupancy of native lands given to the Native Americans by the European powers was “bound” to give way to the “right of discovery” (or “discovery doctrine”) which included the ability to grant, sell, and convey title to the land. Exploitation was inevitable. Johnson v. M’Intosh was an early and significant U.S. Supreme Court decision along those lines — shamefully still the law in the United States — establishing that it would be inconvenient to allow Native Americans to sell land to European-American settlers, thereby creating conditions that allowed appropriation of land by the Federal Government much easier. There is a still very far to go to see equality and fair treatment of Native Americans in the United States. As late as 2009, a class-action lawsuit settlement of $3.4 Billion was paid out by the U.S. Government for malfeasance in dealings with Native people and tribes, including damning admissions of failure to maintain even minimally adequate accounting records for moneys supposedly held in fiduciary trust on their behalf.

In 1964, the year Bitter Tears was released, questions of social justice were all around, if in a slightly different context. This was the year that the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed by the Johnson Administration. The “freedom movement” (also called the “civil rights movement”) tended to be framed as a question of rights for Afro-Americans subjected to discriminatory Jim Crow segregation laws. Attention to Native Americans was something that went beyond a narrow conception of the era being about a merely binary black/white racial divide.

The early/mid-1960s was also the time of the urban folk movement, when the likes of Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and others made “protest songs” popular. It is possible to see Johnny Cash’s album about Native Americans, coupled with appearances at events like the Newport Folk Festival, as purely commercial concerns seeking to expand his audience (and therefore his record label’s customer base). Urban folk and protest music tended to appeal to middle-class, college educated types. Those were important record-buying demographics. Some of his earlier recordings, like Blood, Sweat and Tears (1963) already headed in that direction. He did not come from the same sort of upbringing as most of the protest folk artists. Yet they were listening to him. But for Cash, as someone who emerged from Memphis, Tennessee, and was seen mostly as a country music artist, this broader career move must at a minimum also be seen as something that broke from expectations — though he did release a number of “old west” themed albums that did fit somewhat within the Nashville fold (Ride This Train, Sings the Ballads of the True West). Accounts indicate that Cash had to fight his record label to record the music for Bitter Tears, and he ran an ad decrying how the music establishment won’t give it airplay later on.

Cash rather uniquely bridged a divide between rural and urban audiences. Much of the time that involved finding values that worked for both types of listeners, and working them into song. Joe Bageant wrote Rainbow Pie: A Redneck Memoir (2010), which used his own personal history to portray how rural populations were displaced during the 20th Century, increasingly thrust into urban jobs, without desire to see their old way of life die off. In that way Bageant offered an account of the origins of rural populism, of a kind created by the purposeful machinations of certain political forces. Seeing beyond those forces and working against them, down a path other than the frenzied and directionless reactive anger of populism, were people like Johnny Cash. He grew up on a New Deal farm in Dyess, Arkansas, and called it, approvingly, a “socialistic setup”. In a way, Cash was kind of like country music’s Eleanore Roosevelt. He embodied the legacy of the New Deal coalition’s more compassionate, democratically empowering impulses, seeing the possibility of uniting the needs of the rural poor with the compassion of educated urban elites to promote the well-being of everyone — rather than to pit urban and rural groups against each other for narrow personal gain in a kind of “divide and conquer” strategy. Empathy and community show up as positive ideals, things to actively foster. So it should have surprised no one that when Cash had a network TV show five years later, he was reaching across racial and class divides to feature musical performances from a wider spectrum than just about anything in mainstream media. There was no hesitation in thinking audiences could find a common ground, and appreciate the inherent worth of other points of view. It was awkward sometimes on the TV show, but that very awkwardness was in a way proof that this was a foray into new and unfamiliar territory that made use of untested formulas.

This tribute album project was inspired by Antonino D’Amrosio‘s book A Heartbeat and a Guitar: Johnny Cash and the Making of Bitter Tears (2009). The album was released to coincide with the fifty year anniversary of Bitter Tears. There has been a continued interest in Cash’s music since his death in 2003, with a hit 2004 biopic (Walk the Line), a 2004 book on the making of At Folsom Prison (Johnny Cash at Folsom Prison: The Making of a Masterpiece), an unsuccessful Broadway musical (2006) and soundtrack (2008), a 2007 satire movie vaguely based on Cash’s life and Walk the Line (Walk Hard: The Dewey Cox Story), and boxed set re-releases of all of his Sun (2005) and Columbia (2012) albums. Certainly, some of this is driven by efforts from the Cash estate or other rights owners to posthumously bleed every penny they can from the man’s legacy, just as has happened with Miles Davis, John Coltrane, etc. But aside from whatever crass motivations record labels and heirs may have, it says something about Cash’s continued relevance to audiences that these things are successful enough to keep being released.

Peter La Farge wrote five of the songs from the original album, and Cash the rest (the closer co-written with Johnny Horton). They vary tremendously in tone. “Custer” is a rollicking song that mocks General Custer, who was defeated and killed at the Battle of Little Big Horn by allied native tribes. The single and best-known song from the album is “The Ballad of Ira Hayes,” about a Pima native who fought in WWII for the United States in the Battle of Iwo Jima (in the Volcano Islands). Hayes was one of five U.S. marines and one U.S. navy corpsman pictured in an iconic, award-winning photograph by Joe Rosenthal called “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima,” which was taken on Mount Suribachi during a battle against the Japanese Empire and was widely distributed by a press wire service almost immediately after being taken. Hayes is seen furthest left in the photo. Hayes’ personal history following the publication of the photo, and the war, is a tale that might well have inspired a hundred stories about neglected veterans, the sort made much more common through the Vietnam War.

Some of the songs on Bitter Tears were given a serene, atmospheric treatment that Cash had previously applied to religious songs. “Talking Leaves,” and to some extent “As Long as the Grass Shall Grow,” borrows from Cash’s 1962 B-side “Were You There (When They Crucified My Lord),” recorded with The Carter Family. This is telling about Cash’s approach to Bitter Tears. He saw the treatment of Native Americans as a topic for which the use of religious music was appropriate. Whatever the nearly chant-like wails of a backing singer (either June Carter or Anita Carter) added to religious music, they could add to protest music too. This was the application of moral appeals drawn from religion to social issues. The gambit is that audiences will have the same favorable reaction in both contexts. However, this also had the effect of belittling possible sources of government power. Cash invoking religious song arrangements tends to place (religious) morality above the actions of governments, and suggests that government actions must be submitted to the standards of a higher moral authority. Laws are not a supreme power. They are laws of men, and can be wrong. Crucial in this moralizing is that Cash is not appealing to “the market” or some sort of (non- ethical) economic justification for the treatment of Native Americans. There is no balancing of interests to produce a maximum tradeoff, or efficient equilibrium. Instead he frames the issues in terms of inherent, basic, absolute ideals that are equally applicable to all people. He is singing about human dignity and its loss. He is singing about honesty and perfidy. He is singing about survival and murder. Whatever the context, the government falls on the side of moral wrong, often from a point of view of providing selfish benefits to some groups at the expense of others, and the predominantly racial divides between those exercising power and those subject to it are made clear.

On this tribute project, much of the edge in Cash’s original treatment is gone. The performers seem more interested in paying tribute to Cash the man than the cause he originally championed on Bitter Tears. Certainly, the new performers claim compassion. That is made clear in the liner notes. But remaking recordings from fifty years ago in the sedate, ordinary fashion in which they are done on Look Again to the Wind will challenge no one’s belief’s about the treatment of Native Americans, now or in the past. This is a self-congratulatory shout-out to people who already know better. It is hard to see how this project does anything to advance the interests of Native peoples. That isn’t to say there isn’t good stuff here. One of the most successful re-interpretations is “White Girl” by The Milk Carton Kids. Cash’s original suffered under an ill-suited application of the typical Cash boom-chicka-boom rhythm, and nearly stammered vocals that made it exceedingly difficult to follow the song’s lyrical narrative. At least in this new version, the intent of the story told in the lyrics is clearer. Some of the other performances are a bit more sanctimonious, and the humor on Cash’s original is often missed.

Did Cash ever follow-up on Native American activism after Bitter Tears? Well, not really. When the American Indian Movement (AIM) was most active in the 1970s, Cash had sort of moved on and shifted his focus to prison advocacy. He met with politicians and appeared in prisons, trying to make positive differences and call attention to the treatment of prisoners. He was no longer calling attention to the treatment of Native Americans in the present. While that was too bad, in some respects, it shouldn’t take away from what he did do to support the plight of Native Americans. Bitter Tears is still a compelling album fifty years later. Look Again to the Wind has none of those compelling qualities. It is actually a pretty boring album — as boring as any Hal Willner tribute project. But, at a minimum, it presents a chance to revisit Cash’s original effort and appreciate what an incongruous feat it was.