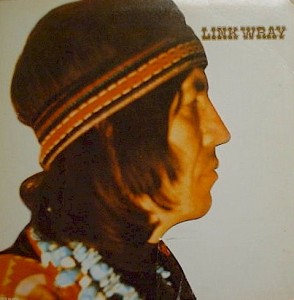

Link Wray – Link Wray Polydor PD-24-4064 (1971)

It is often the case that musical innovators languish in obscurity, or something close to it. In rock, there are examples all over, like The Velvet Underground. Link Wray is another. He is best known for his raw 1958 instrumental classic “Rumble,” which paved the way for The Kinks‘s “You Really Got Me,” Pete Townshend‘s monster guitar power riffing with The Who, and much of the surf-rock genre. But commercial success didn’t really come his way. “Rumble” was something of a flash in the pan hit, but after recording a whole album of prime material, his clean-cut label dropped him without releasing his recordings — a story that might have been quite different if Wray had somehow found his way to the attention of Sun Records. He bounced to a few other labels, but the momentum from “Rumble” was largely lost and soon the moment had passed to other sounds. He became something of a footnote in rock history: the guy who added raw, improvised (as in makeshift) distortion to rock guitar.

If all you know of Link Wray is “Rumble,” or some excellent if now little-known follow-up instrumentals like “Raw-Hide,” “Jack the Ripper” and “Fat Back,” or even his later career efforts like Barbed Wire that modernized his original sound without losing the raw energy, Link Wray might be a surprise. It sounds nothing like Wray’s signature early instrumental rock. This is music that bears more resemblances to the country rock of The Basement Tapes by Bob Dylan & The Band crossed with the swampy southern rock of Creedence Clearwater Revival or Dr. John, but with searching, moody and almost existential songwriting of the kind that showed up later in the decade on Dennis Wilson‘s cult classic Pacific Ocean Blue. Link Wray is the blueprint for The Rolling Stones‘s Exile on Main St. Wray’s soulful vocals recall Felix Cavaliere of The Rascals. That is no small feat. Link Wray’s early recordings were instrumentals for a reason: he had his left lung removed after contracting tuberculosis (consumption) during military service in the Korean War.

By the dawn of the 1970s the center of gravity for rock — and by extension all pop music — was shifting away from New York City and Britain toward California. West Coast studios were ahead of their Eastern peers in adopting more elaborate recording technologies and techniques. The very sound of rock music was also growing more complex and intricate, with symphonic rock, rock operas, glam and prog gaining steam. Even just within the realm of singer-songwriters, the more overtly produced and orchestrated styles of the likes of Elton John and Randy Newman were overtaking the simpler, mostly acoustic folk of popular 60s performers epitomized by Joan Baez. Amidst all that Link Wray was yet again cutting against the grain of the industry establishment. He set up his own three-track studio in a converted chicken coop on his family’s farm in Accokeek, Maryland. In that setting he experimented with his own sound in relative seclusion (as with The Basement Tapes). He recorded this in that primitive fashion. The album is no joke. It exudes complete honesty, even to the point of being somewhat blunt and ungainly at times. But Wray’s lethargic guitar sounds just fine in a georgic setting far removed from his characteristic power chords. Muffled piano and vocal choruses bolster the hopeful messages nestled in the murky, indistinct sound. Link Wray is a little beauty that deserves another look, hopefully someday to be rescued from the obscure and dusty corners of early 70s rock.