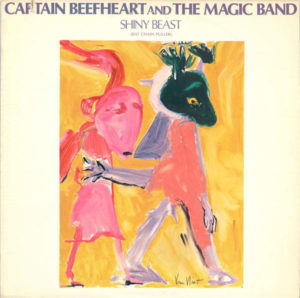

Captain Beefheart and The Magic Band – Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) Warner Bros. BSK 3256 (1978)

After a pair of widely panned albums in 1974, a 1975 collaboration, and a few years without any new albums — much of these travails the result of his entire backing band quitting in the face of Stalinist leadership tactics — the Captain returned amidst the punk era with one of his best. He had actually recorded an entire album (Bat Chain Puller) then lost control of the master tapes as part of a tangentially-related royalty dispute between owners of his label. He and yet another reconstituted version of The Magic Band then re-recorded some of the tracks, and some completely new ones, for a different label. Bat Chain Puller tracks omitted from Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) showed up in later re-recordings on Doc at the Radar Station and Ice Cream for Crow.

Anyway, Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) is something of a summary of many things the Captain had been doing in the 1970s along with a few new hot takes. The delivery is slicker, but, surprisingly, that generally works for rather than against the music. The album opens with “The Floppy Boot Stomp,” which signals that it was going to draw from the sort of idiosyncratic music that the Captain had been making in the Trout Mask Replica and Lick My Decals Off, Baby era but had abandoned in recent years. But the second cut, “Tropical Hot Dog Night,” channels Jimmy Buffett (and maybe also Flowmotion) in service of a statement of hesitant yet macho sexuality — a song reprised decades on by PJ Harvey as “Meet Ze Monsta.” A latin flavor later reappears on the song “Candle Mambo” too. This version of The Magic Band includes a brassy horn section that is somewhat unique, given that other recordings leaned more on woodwinds than brass. “Suction Prints” even sort of resembles punk — the first part of the song has a rhythm not too far off from Iggy Pop and The Stooges‘ hardcore punk B-side “Gimme Some Skin.” “Harry Irene” is a kind of ironic/nostalgic cabaret song (compare cuts like “Jean the Machine” and “Joe” on Scott Walker‘s ‘Till the Band Comes In). Sure, in “Owed T’ Alex” and “Apes-ma” (the one track held over from the original sessions), there are a few throwaway tracks here. But for the most part this album is great from top to bottom.

So how does this compare to the aborted Bat Chain Puller album (eventually released in 2012) this originally replaced? Well, in a way the original is even better — a little rawer, sparer and unified while still in territory that seems uncharted. But the Shiny Beast (Bat Chain Puller) incarnation replaces prominent keyboards with its horn section that adds a new dimension, and the caribbean flavor of “Tropical Hot Dog Night” was completely absent on the original recordings. And the original lacked a song quite that good. The general eclecticism and fullness of the re-recordings is also something different and an asset in their favor. So maybe the new version of the album is better? Frankly, it is pointless to pick a favorite between Bat Chain Puller and Shiny Beast because they are both great. Beefheart fans are going to want to hear both (although the original recordings were officially released in 2012, they fell out of print quickly).