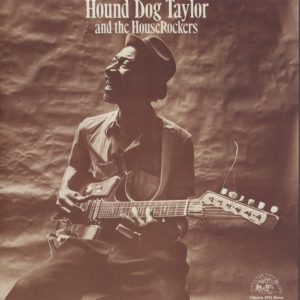

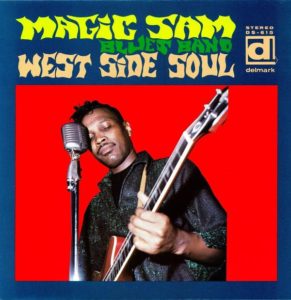

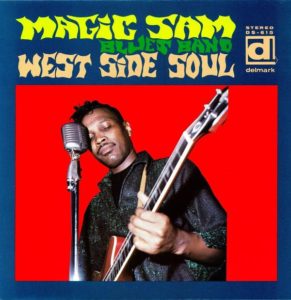

Magic Sam Blues Band – West Side Soul Delmark DS-615 (1968)

Right off with “That’s All I Need,” Magic Sam establishes that the listener is in for something very special. His soulful voice trembles with vibrato and charms you into his world. The first track is a transcendent blues moment. Not even the rest of the album duplicates those opening lines. Coming in behind the metallic reverb of the guitar, his hope and longing are never fully resolved in song. Magic Sam may have the blues, but he pushes everything back if just for a few minutes.

A legend of electric blues, Magic Sam died tragically young. Before he checked out, he left a legacy that has not been forgotten. He injected a raw and punchy version of the dynamic singing style of a soul (or gospel) singer plus garage-y guitar playing with a faint hint of psychedelia into the electric blues lexicon, while preserving a rhythmic style style reminiscent of acoustic blues of the 1930s and 40s that frequently turns to boogie-woogie. It strikes the perfect balance between delta roots and smooth Chicago styles, with an openness to new developments from genres outside just the blues. The sound jumps from laid-back strumming to cutting solos. Vocals push and prod the band. Guitars pull the beat along at a brisk pace, always responsive to the guiding of Sam’s vocals.

In a unique way, West Side Soul is upbeat and redemptive — electrifying. While covering all the customary blues elements, Magic Sam goes further to lift listeners off the ground. There is always the hanging question of how his stories end, but Magic Sam likes to say there probably is a happy one.

Magic Sam begs listeners to struggle alongside him through his tragic world. The themes are easy to relate to. Heartbreak is not a foreign concept. “I Found A New Love” and “All of Your Love” are not pillars of confidence. Despite his shaky emotions, Magic Sam sets out for something better. West Side Soul is a rare glimpse into a personal transformation. Hesitation weighs against possibility in an eternal conflict.

Songs overflow with energy. “I Don’t Want No Woman” is a frustrated rocker. Magic Sam pleads as much with himself as his woman. The assertion of semi-independence is more a desire to explore for while longer. On Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago” the band stretches out in a sly groove. The song now reflects a permanent home rather than a mythical paradise. Mighty Joe Young strides confidently on guitar. Odie Payne is a fury on drums. Stockholm Slim on piano and Earnest Johnson on bass round out this killer band (with Mack Thompson and Odie Payne III featured on three tracks).

West Side Soul is a highly revered blues album. It is also a perfect introduction to electric blues for anyone interested in discovering postwar blues. Not bad for a debut at all.