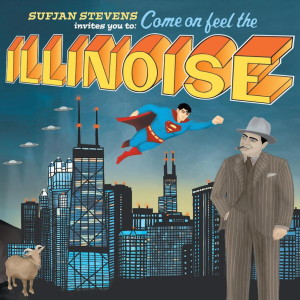

Sufjan Stevens – Come on Feel the Illinoise Asthmatic Kitty AKR 014 (2005)

The darling of college radio and the American “indie” rock press, Sufjan Stevens’ Come On Feel the Illinoise (often mistakenly identified as Illinois) is a sedative for the youngest national public radio demographic. That said, the album is even still a bit of a disappointment. It marks a significant downward slide from Stevens’ wonderful, if flawed, Greetings from Michigan: The Great Lake State. It’s also a lesser effort than his inconsistent but rewarding Seven Swans. The problem, in short, is that Stevens has become the Cole Porter of christian rock. Now, many might say that comparing someone to Cole Porter would be a complement. Understand that it is no complement here.

Cole Porter wrote finely crafted lyrics that wandered aimlessly and unwittingly amid the melodramatic. Porter’s sense of harmony was extremely limited, and he often dwelled on the same harmonies across countless songs. His only redeeming quality really was his blunt use of melody. He could, after all, write some memorable refrains from time to time. Delivering those, without any dressings, was about his only talent.

Sufjan Stevens fairs much the same. Come On Feel the Illinoise is his second entry into a purported series of albums inspired by and ostensibly about each state of the United States. Moving beyond the borders of his home state of Michigan, here he muses on historical persons and events in an effort to pull sentiments from isolated events. Mostly, these quaint attempts overplay the basic implausibility of constructing something genuine in set pieces built around historical tidbits that are the equivalents of popular newspaper headlines. The album also underplays any sense of unity in the subject matter, so that the songs feel like a journal entries documenting a loose tour of the most peripheral regions of the state of Illinois. The pessimism inherent in that approach is only addressed, if at all, through periodic invocations of christian dogma.

The songs tend to recycle ideas from Stevens’ previous albums. Familiar rhythms and harmonies return again and again. In those respects, Stevens works from a limited palate. Repeating himself has offered only slight improvements over his earlier work. This leaves his melodic sense to carry the album. Rather, it carries a few of the album’s songs. The magical “ Decatur, or, Round of Applause for Your Step Mother!” is buoyed by soft and lively guitar and banjo phrases that gently sway and gently ascend. “The Tallest Man, The Broadest Shoulders” also comes alive with a lively tempo. “Come On! Feel the Illinoise!” adds lovely counterpoint to the vocals through recurrent string arrangements. Unfortunately, these are rarities. Most other songs are ultimately too ambitious for Steven’s songwriting skills.

Sufjan Stevens has talent. That much is clear from his previous albums. Yet when it comes to songwriting, and historical research, he has proven to be a bit of a philistine. He should get less of his history from the likes of children’s books and newspapers and more from Howard Zinn.

Come On Feel the Illinoise relies too much on an assumption that history offers an escape from reality. On its own merits, the album seems like just another “inoffensive” pop album. It’s a better pop album than most, sure, but not on the level of achievements of the greatest American pop songsmiths. Sufjan Stevens’ self-satisfied righteousness is holding him back from becoming a mature songwriter. It’s time for him to grow, musically.