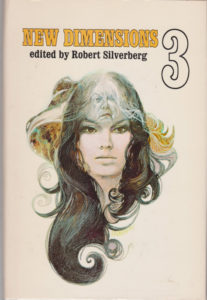

Ursula K. Le Guin – “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” from New Dimensions 3, Robert Silverberg, ed. (1973)

Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” presents an excellent example of what Alenka Zupancic described as “liberal blackmail”. Le Guin tells a story of a “utopian” city that has a child imprisoned in essentially a torture dungeon. The liberal blackmail is stated quite succinctly by her:

“If the child were brought up into the sunlight out of that vile place, if it were cleaned and fed and comforted, that would be a good thing, indeed; but if it were done, in that day and hour all the prosperity and beauty and delight of Omelas would wither and be destroyed. Those are the terms. *** The terms are strict and absolute; there may not even be a kind word spoken to the child.”

This is blackmail because it insists on a reductionist binary. Either people stay in the city and keep torturing the child, or they walk away from Omelas. No third option is permitted. It is liberal because the first option (where the child is tortured) is basically standard liberalism. Domenico Losurdo has explained this in books like Liberalism: A Counter-History (2014). Liberalism is a politics of exclusion, a kind of false universalism that separates the society of the free from those unworthy of freedom. Le Guin’s short story is basically an extremely blunt depiction of this basic — if disavowed — premise of political liberalism. Sure, other social structures like feudalism oppress certain groups but they don’t profess freedom like the society of Omelas that Le Guin describes in the story.

The other option, of “walking away from Omelas,” is basically what the philosopher Hegel called the “Beautiful soul” problem. Here, Zupancic explains the dynamic well:

“The rise of the affect(s) and the sanctimony around affective intuition are very much related to some signifiers being out of our reach, and this often involves a gross ideological mystification. Valorization of affectivity and feelings appears at the precise point when some problem — injustice, say — would demand a more radical systemic revision as to its causes and perpetuation. This would also involve naming — not only some people but also social and economic inequalities that we long stopped naming and questioning.

“Social valorization of affects basically means that we pay the plaintiff with her own money: oh, but your feelings are so precious, you are so precious! The more you feel, the more precious you are. This is a typical neoliberal maneuver, which transforms even our traumatic experiences into possible social capital. If we can capitalize on our affects, we will limit out protests to declarations of these affects — say, declarations of suffering — rather than becoming active agents of social change. I’m of course not saying that suffering shouldn’t be expressed and talked about, but that this should not ‘freeze’ the subject into the figure of the victim. The revolt should be precisely about refusing to be a victim, rejecting the position of the victim on all possible levels.

***

“this bind derives precisely from the subjective gain or gratification that this positioning offers. (Moral) outrage is a particularly unproductive affect, yet it is one that offers considerable libidinal satisfaction. By ‘unproductive’ I mean this: it gives us the satisfaction of feeling morally superior, the feeling that we are in the right and others are in the wrong. Now for this to work, things must not really change. We are much less interested in changing things than in proving, again and again, that we are in the right, or on the right side, the side of the good. Hegel invented a great name for this position: the ‘beautiful soul.’ A ‘beautiful soul’ sees evil and baseness all around it but fails to see to what extent it participates in the perpetuation of that same order of things. The point of course is not that the world isn’t really evil, the point is that we are part of this evil world.”

“Too Much of Not Enough: An Interview with Alenka Zupančič”

If her explanation still seems difficult to grasp, the concept can be more succinctly summed up this way:

“They play the Beautiful Soul, which feels superior to the corrupted world while secretly participating in it: they need this corrupted world as the only terrain where they can exert their moral superiority.”

Slavoj Žižek, Refugees, Terror and Other Troubles with the Neighbors: Against the Double Blackmail (2016).

Those who “walk away from Omelas” do nothing to change its underlying horror. They only go away to exist outside its geographic borders, thereby using the existence of Omelas to exert their moral superiority. In other words, they need Omelas and its torture dungeon in order to self-identify as morally superior individuals — walking away actually supports the continued functioning of Omelas and its torture dungeon. The “beautiful souls” who walk away merely turn the traumatic experience of confronting the torture dungeon into social capital, but rationalize its continuation.

In the 1970s, Le Guin took a turn towards neoliberal feminism, or what might be called cultural feminism or even bourgeois feminism. Usually portrayed as her becoming more politically conscious, rather the opposite is true. She really made a turn much like the so-called “new philosophers” to the political right. She embraced the tactics of identity politics and the valorization of victimhood status. She was much more of a careerist opportunist than she is often portrayed by supporters, cynically invoking certain concepts to enhance her public status (and boost her book sales) without doing a whole lot to meaningfully change anything beyond a few gendered pronouns, with at most a slightly populist twist. Her best work was in the 1960s and early 1970s, and it dealt with typical concerns of the time. For instance, A Wizard of Earthsea (1968) deals with the destructive power of envy, something that French writers were grappling with under the rubric of ressentiment. She jettisoned those things in the 70s and instead dwelt on identity politics. There is reason to suggest that “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas” is at bottom anti-communist propaganda. Little if any of her writing after her anarchist masterpiece The Dispossessed (1974) is very highly regarded by readers.

So, back to the short story. Le Guin cited William James, and his “The Moral Philosopher and the Moral Life,” claiming that only those who remain in Omelas are accepting a bargain. But this is demonstrably false — those who walk away from Omelas are bargaining too and merely offer a different rationalization. The most obvious ethical response that avoids an element of bargaining is to simply reject Le Guin’s stupid Manichean premise and do precisely what she states is impossible: change the structure of the society of Omelas. An excellent analogy in (science-)fiction is the way Captain James T. Kirk in the Star Trek franchise defeated the “Kobayashi Maru test” as a student at “Starfleet Academy” by reprogramming the test computer to make the no-win scenario winnable. Or Josef Stalin’s famous retort to a journalist who asked him which deviation is worse, the Rightist one (Bukharin) or the Leftist one (Trotsky), responding, “They are both worse!” Franz Kafka‘s The Trial (1925) included the parable of the door to the law, which is also more or less a relevant counterpart, if a more individual and pessimistic one about overcoming seemingly impossible obstacles. The point is to reject the false binary choice the short story presents as a form of blackmail, conspiracy, or propaganda. Or, let’s tentatively grant Le Guin her conceit that the “terms are strict and absolute” in this Omelas society. Then, the solution is Bartleby politics, after the character in Herman Melville‘s short story “Bartleby, The Scrivener” who did nothing to carry out his social role but to answer, “I would prefer not to.” Would you stay in Omelas? “I would prefer not to.” Would you walk away from Omelas? “I would prefer not to.” Ah, but then the terms would suddenly not be so strict and absolute as the society fails to reproduce itself and disappears…at great peril and cost to those who prefer not to, like Melville’s Bartleby who dies in jail. So, it would be Bartleby politics or you walk away from Omelas and come back with an army to destroy it…