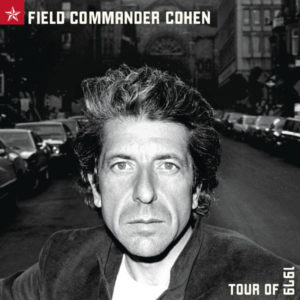

Leonard Cohen – Field Commander Cohen: Tour of 1979 Columbia CK 66210 (2001)

Leonard Cohen was first a poet then, perhaps, a musician. His monotone voice is something you love or hate. This album features recordings from four dates of a 1979 tour in the U.K. While not exactly a live greatest hits collection, Field Commander Cohen does end with his classics “Bird On the Wire” and “So Long, Marianne.” The recordings are very good, only adding as much music as necessary.

The sheer genius of Cohen’s lyrics dominates everything he has done. His music is best described as an acquired taste. The durable ideas and complex emotions unfold slowly. It takes at least two or three listens to grasp Cohen’s purpose. The liner notes are particularly helpful with full listings of all lyrics, which are sometimes understood easiest when read. Vocals add another layer of meaning to Cohen’s words, which can be confusing to new listeners.

Songs portray likable losers and bare insecurity. The faux doo-wop of “Memories” is a sweet story of longing, complete with innocent rejection. “The Stranger Song” captures the appeal of a singer/songwriter’s isolation, recalling the best of Cohen’s early work. “Lover Lover Lover” pauses for a long instrumental passage, while a duet on “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye” highlights the song’s sappy wit. “The Guests” is a twisted vision of desire. These songs are deep and profound. Cohen can take you where few other artists can, and offer a glimpse deep into his personal experience.

The band plays well. Overall the sound is mellow, even bland, but this seems like a calculated plan to showcase the lyrics. At times the spark of live performance breathes new life into the songs. Guest appearances by Raffi Hakopian and John Bilezikjian spice up the arrangements. Jennifer Warnes and Sharon Robinson sing backup, adding refreshing vocal depth. The album ends with arguably the best performances.

Leonard Cohen was about as strange a “rock star” as there ever was. He came to popularity near the end of the big 60s folk movement. His unique blend of poetry and music would never catch on in another era, and is still unbelievable as it actually happened. Leonard Cohen could be a great bluesman (though his voice would defy that genre). Rather than the blues, he fashioned his own blend of comedy and tragedy. This album is a good example those talents.

Field Commander Cohen is a nice album for long-time Cohen fans wanting more live material, and is still a good introduction for new listeners (it strikes a good balance between accessibility and potency), though there are many better live Cohen albums, like Live at the Isle of Wight 1970 and Live in London.