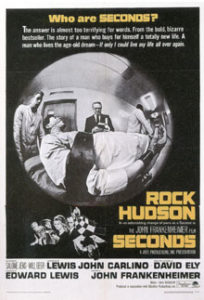

Seconds (1966)

Paramount Pictures

Director: John Frankenheimer

Main Cast: Rock Hudson, John Randolph, Salome Jens

Arguably John Frankenheimer’s best film, Seconds is an eerie thriller with an engaging plot, fine acting (and casting), and appropriately stark cinematography by James Wong Howe. Frankenheimer was a political person, associated with Hollywood’s left. Here he uses the previously blacklisted actors John Randolph and Will Geer. Taking that sort of information as context, Seconds plays with the clash between the conservative American culture held over from the early post-war years, and the rise of the counterculture, asking some intriguing questions without succumbing to overly optimistic triumphalism or naivity, as befell some of the less lasting films of the era that tackled similar topics.

The basic story is that Arthur Hamilton (John Randolph) is a banker of some sort, with an ivy league education, and a boring upper middle class existence with a bloodless marriage and a daughter who is out of contact. But he gets a call from an old friend believed dead, who leads him to a mysterious Company that promises to make its customers reborn, setting them up with new lives after staging their deaths –with the help of CPS (cadaver procurement services) — and performing extensive plastic surgery. Scenes with executives from the Company “making the sale” to get Hamilton to commit to the large fees and sign off on the necessary paperwork are wonderful in how they strike a perfect balance between mysterious awkwardness, ominous paranoia, and dry humor. So Hamilton becomes Antiochus “Tony” Wilson (Rock Hudson), a painter in Malibu, California. While under the care of of John (Wesley Addy), an employee of the Company, he meets Nora Marcus (Salome Jens). She takes him to a hedonistic, free spirited grape stomping party and he gets his first taste of a new kind of life. But then John organizes a party for the neighbors, and a drunken Wilson (Hudson was actually inebriated for the scenes) recklessly lets slip that he is a “reborn” and had a past life. But the surprise is that most of the party-goers are also reborns, or employees of the Company, or maybe both. Wilson then stubbornly returns to his old home and visits his (former) wife, concocting a story that he is an acquaintance of Hamilton’s. Wilson can’t seem to accept his new life. So he goes back to the Company to ask to be reborn again. And then? He makes the disturbing realization that the reborn program is largely a failure, and that CPS uses the failed reborns as the corpses to stage the deaths of new customers…

A Criterion Collection DVD issue of the film includes numerous commentaries that take a very fatalistic view of the film. These commentators each state (almost verbatim) that the film illustrates how “you can’t change who you are.” In The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology (2013), Slavoj Žižek discusses this film and takes a notably different position, drawing from Herbert Marcuse. He explains that while Tony Wilson’s past in its material existence, was erased, but his dreams remained the same as before. Crucially, he adds:

“We are not simply submitted to our dreams — they just come from some unfathomable depths and we can’t do anything about it. This is the basic lesson of psychoanalysis and fiction cinema. We are responsible for our dreams. Our dreams stage our desires, and our desires are not objective facts. We created them, we sustained them, we are responsible for them.”

In this, he rejects the fatalistic notion that changing our dreams is impossible (it would have been great if the Criterion Collection DVD had included a clip of that commentary from the Žižek film). Here it is significant that the film shows Rock Hudson’s character undergoing all sorts of treatments from the Company, mostly physical and based on the accoutrements of his new Malibu home, but never any really psychoanalysis or other mental exploration — some (apparent) psychologist from the Company merely tells him what his real dreams are, based on some kind of “truth serum” drug-induced self-revelation. He never really tries to change his dreams to fit a new lifestyle; instead, he clings to the escapism that sustained his previous, professional, “old boys club,” consumerist lifestyle, just without actually being present in that sort of living context.

There are some similarities here to John Cassavetes‘ independent feature Faces (1968). Yet Frankenheimer’s film is overall the better of the two: despite gripping scenes and the customary great acting of any Cassavetes film, the overall story of Faces seems dated now. Faces focused on the claustrophobic conformity of middle-class (really, upper middle-class) lifestyles of the 1960s, contrasted with the lives of outsiders (a prostitute, a hippie), and explores how the middle-class types struggle to enjoy themselves. This, again, is a basic premise of psychoanalysis. But, returning to comments from Žižek, in the documentary Žižek! (2005), he discussed how contemporary society commands everyone to “enjoy” themselves, and in The Reality of the Virtual (2004), he elaborated that the role of psychoanalysis becomes, not to free a person from his or her inner inhibitions preventing access to enjoyment, but to open up a space in which a person is allowed not to enjoy himself or herself ( this is the notion of ego-ideal vs. ideal ego). Faces concerns the former, while Seconds takes a more modern view, engaging the latter.

Rock Hudson is amazing in the film, conveying the unstable tensions between his new (handsome) appearance and supposedly fantasy lifestyle with the lingering ennui and emptiness that dominates his mental state. But really, all the smaller parts are excellently played too. Near the end of the film, Will Geer, the old man who founded the Company, reveals to Wilson that he knew for a long time that the entire “Reborn” program was a failure, but the Company had become so large and the employees depended on it, not to mention his board of directors pressuring him…so he keeps it going. This cynical portrayal of the sinister behavior of “vested interests” (to use Thorstein Veblen‘s term), reveals how it slides easily into the “banality of evil” (to now adopt Hannah Arendt‘s term). That scene is so well-executed that it is of no concern how blunt the characterization is of businessmen literally killing people to maintain a pointless cycle of profits.

There is a bit of heavy-handed camera work and editing, with oddly-angled shots and distorted optics, particularly in the opening scene, but otherwise this is a film that gets just about everything right in its realization. From the script down to almost every technical detail there is much to praise here.

If this film is to your liking, aside from Faces, also try some of Samuel Fuller‘s great B-movies of the mid-60s, The Naked Kiss (1964) and Shock Corridor (1963). Any of the early “New Hollywood” films would be good choices too.