Link to an article by Elliot Murphy:

Month: December 2015

Paul Robeson – Spirituals

Paul Robeson – Spirituals Columbia Masterworks Set M-610 (1946)

Possibly Robeson’s best album. There are few singers with a voice as capable of commanding of attention as Paul Robeson’s. His deep, resonant bass-baritone is so iconic that the man’s portrait should probably appear in dictionaries next to the word “dignity”.

The recording of “John Henry” included here is one of Robeson’s very finest. The Legend of John Henry is an old neo-Luddite folk tale, based on a real historical person (or amalgam of many real persons) working to build a railroad line, probably as convict labor after the Civil War, about a poignantly suicidal triumph of labor over the technology that owners of capital wield to destroy the means of workers’ support and dignity. John Henry defeats a spike-driving machine in a one-on-one competition, only to die of exertion. Lawrence Brown‘s somber piano provides deftly understated accompaniment. Brown plays in response to what Robeson sings, in the black tradition of call-and-response. The way Robeson sings is amazing. He uses controlled vibrato, just as any trained opera or bel canto pop singer would. His enunciation is impeccable. Every word is booming yet unmistakable. But he sings the song with non-standard diction. This places him halfway between vernacular music (true folk “spirituals”) and the ordained and accepted music of society’s ruling classes (“hymns” in the religious context). Spirituals came after Robeson’s political radicalization, and it is easy to look back at it and see how his approach to performance injects the vernacular into dominant forms as a kind of bottom-up revolutionary act, as performed by a black man in Jim Crow America who sings so well and with such unmistakable facility for bel canto pop music that he cannot be dismissed as an untalented ruffian making a bunch of mere noise.

Michael Denning‘s book Noise Uprising chronicled the revolution from below made possible from 1925-30 by the advent of electrical recording technology — before the Great Depression collapsed the global market for such records. Paul Robeson represents a different sort of revolutionary stance, though not necessarily an entirely different one. Robeson took advantage of electrical microphone technology to capture his voice in ways never before possible (his record label recorded him with the very latest technology). He also balanced the expectations of the powerful with the interests of the downtrodden. And he did so very, very well. His use of vernacular elements was more limited though, focused on more precise, subtle mobilizations in his vocals. Take “Balm in Gilead,” which slurs the words “there is” to sound a bit like “dere is” in a line otherwise enunciated with stately exactitude. These effects let you know which side Robeson is really on. He can sing in accordance with all the rules the powerful insist upon, but he carefully deviates from them, to inform the audience that he is choosing to do so, for purposes that are manifestly not dictated by the powerful.

On “Nobody Knows de Trouble I’ve Seen” Robeson sings the last line “glo_ry, Hallelu__jah” with an abrupt shift in his intonation of the last syllable of the word “Hallelujah” to express a kind of release and hopeful promise that stands in contrast to the somber weariness of the rest of the song.

Lawrence Brown sings accompaniment too. On “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho” he adds responses to Robeson’s leads. Brown’s higher pitched voice, and quicker, less noticeable vibrato are counterpoints to Robeson’s booming voice. The tempo is much faster than most of the songs on the album too. It is followed by another duet song, “By an’ By.” Brown’s lines are phrased in a heavier vernacular, though one that comes across as slightly studied and academic — in other words, staged and inauthentic. This places Robeson is a kind of hero role, making his voice sound more commanding and impressive.

The albums wraps up with three tour de force solo vocals: “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “John Henry” and “Water Boy.” The last two songs are part of Robeson’s standard repertory. He performed those songs in most concerts and recorded them multiple times. “Water Boy” uses melisma to the maximum. Robeson’s use of vibrato is also a thing to behold. He carefully controls the vibrato over long, sustained notes to match the rhythm of his vocal phrasing. Much like “John Henry,” “Water Boy” is a kind of hero tale, framed as (presumably) an adult boasting to a “water boy” of his strength and capabilities as a worker. It is at once a celebration of labor and a vehicle perfectly suited for a black man in the Jim Crow era to demonstrate prowess as a singer.

If all this makes Robeson seem too much of an activist, when all he was doing was singing, then it is worth considering what happened to him in the following decades. His passport was illegally denied and he was blacklisted. His son also alleges that the CIA surreptitiously conducted “mind depatterning” on him as part of Project MK-Ultra (probably with LSD). The powerful knew that Robeson and his music were indeed a threat to white supremacy and other forms of oppression. It is a bit difficult to walk away from hearing a Robeson recording like Spirituals without some degree of respect, if not awe.

Michael Hudson – The IMF Changes Its Rules to Isolate China and Russia

Link to an article by Michael Hudson:

“The IMF Changes Its Rules to Isolate China and Russia”

Bonus link: “IMF Forgives Ukraine’s Debt to Russia”

Gavin Mueller – Shackling the Masses With Drastic Capitalist Tactics

Link to an article by Gavin Mueller:

“Shackling the Masses With Drastic Capitalist Tactics”

Bonus link: “Pharma Bad Boy Martin Shkreli, Kaye Scholer Partner Arrested”

Tom Zé – Correio da Estação do Brás

Tom Zé – Correio da Estação do Brás Continental 1-01-404-177 (1978)

Tom Zé was one of the most explicitly political of all the Brazilian Tropicalistas. Later in his career he would call his music imprensa cantada (“sung journalism”). But his early musical efforts found him associated with the CPC (Centro Popular de Cultura), which was part of the left-wing National Students’ Union that was in turn linked to the Brazilian communist party. This was during the time before socialist President João Goulart was ousted in a U.S.-backed, right-wing military coup. As Christopher Dunn has commented, “Zé’s songs often reminded listeners of deep class inequalities and forms of social exclusion in the sprawling metropolis.” There was a dogged tendency for his music to mock powerful elites and their culture, revealing their hypocrisies and contradictions. Like others who were a part of the tropicalismo movement, he utilized cultural artifacts considered base and distasteful by elites, developing a kind of solidarity with the underclass by merging the highbrow and the lowbrow. From a slightly different perspective, these negated or abject cultural artifacts ironically stand for universality, as a point of exception in the allegedly democratic global capitalist (neoliberal) system, giving lie to the supposed goodness and fairness of society by showing how the cleaving of musical forms into the acceptable and unacceptable symbolically reinforces domination of the weak by the powerful and by uniting different musical factions with a common purpose (namely, fighting oppression). This had the effect of erasing the subtly elitist satisfaction derived from the very essence of making highbrow/lowbrow distinctions at all (quite apart from the “substance” of the highbrow or lowbrow). He had a unique, outsider’s ability to do this as someone who grew up in what was considered the rural, inland netherworld of Irará, Bahia (north of the state capital Salvador), silently controlled by absentee landlords, but relocated to a big city as an adult in order to work from the urban metropolis of São Paulo. Even his tropicalist contemporaries noted his rural accent when he sang. His outsider perspective never really went away, but it mutated into concerns for deeper, less obvious topics.

Zé stuck with some of the underlying impulses of tropicalismo longer than most of the original cadre of proponents, even as his precise methods did depart from the original tropicalist manifesto over time. As my friend Toni put it:

Years after the great innovators Caetano & Gil began to embrace the banality of western popular culture instead of ridiculing it, the true genii stand out. João Gilberto has retained his integrity by isolating himself from the popular spotlight and the Mutants are respectfully celebrating their past glory, just to pull some arbitrary examples from the golden period of Brazilian music. This is all fine and dandy, but Tom Zé, always the underdog, is not satisfied with just rehashing his former glory: he has to innovate, to create, to explore.

These qualities were unmistakable during Zé’s late-career resurgence. Yet in the late 1970s, as his popularity was already starting to fade, there was still a question of whether Tom Zé was continuing to innovate or starting to capitulate.

Like most tropicalismo, Zé’s music had to this point relied heavily on ironic use of popular musical forms with kitsch value. But here, he suddenly seems to be using some popular 1970s rock forms more directly and earnestly (“Morena,” “Carta”). There are some warm rock keyboards and near crooning. So, while listeners had always needed to sort out the hidden meaning of Zé’s cutting irony, there was also the added challenge of deciding when he was being ironic at all. He dabbled with this before (see “O riso e a faca” from his second self-titled album Tom Zé), but the technique was more prevalent here. This is perhaps why Correio da Estação do Brás is seen as an abrupt rupture in Zé’s recorded catalog. For some, this was when he washed up and his music lost what it once had. Others like the album — though some consider it under-appreciated, most Zé admirers rarely place it above the middle of the pack of his albums.

One way to look at Correio da Estação do Brás is to give Zé credit for recognizing that he could not just keep making the same kind of oddball music forever. Given that the man’s career prospects declined in the 1970s, perhaps one can read his emphasis on conventional song structures as being about finding enjoyment (if not remuneration) outside of the revolutionary content of his earlier work. But there also seems to be recognition that the ironic distance that his music long proposed was maybe smaller than first assumed (or should be smaller). An artist cannot stand completely apart from the concerns of mass audiences, even if those mass audiences are driven by crass consumerism and distasteful inequities. There are forms of dependency involved. But then what? Zé strikes an intriguing balance, carrying forward a lot of what he had been doing before, but also trying to make use of whatever redeeming elements of popular 1970s rock he could. He attempts both of these things at the same time. In that way he refuses to stand above or apart from the the lowbrow and the social groups associated with it. By adapting to “easy” popular forms, but not completely or consistently, Zé ends up making what, from a conceptual standpoint, is among his more difficult albums, even if from a technical standpoint it contains some of his most unabashedly pleasing and straightforward music. For instance, what isn’t to like about his plaintive, mellow singing on “Morena”? Is it that far off from the Commodores’ 1978 R&B hit “Three Times a Lady”? Yet placing some lovely melodic statements among ironic ones Zé makes the listener question what she enjoys, and whether she should be expected to enjoy what she hears. The listener cannot automatically enjoy an assuredly superior, ironic posture. In fact, the listener may be slightly horrified to have the self-image of ironic superiority shattered. This is a very different kind of message than Zé’s earlier work, but still a daring and revolutionary one in its own way.

So, on the one hand, listeners skeptical of the weirdness perennially rejoiced by many Zé fans may find that Correio da Estação do Brás presents familiar music elements that are superficially appealing, making this a potential entry point to his music. On other hand, the reason Tom Zé is known internationally is not for singing smooth pop melodies but for challenging and reconstructing them to present new and different meaning, so listeners who balk at those parts of this album that push against convention will perhaps venture no further into his recorded works from here. That is the challenge presented by Correio da Estação do Brás.

There is something to be said that this album should not be overlooked, though, even if its most nuanced accomplishments may only become apparent when contextualized against what led up to it. It is really quite a good album. Then again, it is a bit difficult to locate a bad Zé album, in a career as irrevocably unique as any in pop music.

John Russo – Deindustrialization, Depopulation, and the Refugee Crisis

Link to an article by John Russo:

Ryan Adams – Ten Songs From Live at Carnegie Hall

Ryan Adams – Ten Songs From Live at Carnegie Hall Blue Note Records B002263402 (2015)

Ryan Adams comes across as a pretentious twat. His music can overplay the histrionics. In just about every marketing photo he has carefully tousled hair, probably a tattered jacket, and perhaps even a cigarette dangling from his lips. And yet, in spite of all that, he can write good songs. The ever-present burning emotional content is usually framed as existential crises of an individual navigating complex and difficult to the point of oppressive social relations. This album, a selection of tracks from a larger, limited edition boxed set, is just Adams solo and acoustic. There is guitar and piano, some harmonica. The effect is a bit like when the urban folk movement of the 1960s sent its brightest starts to the Carnegie Hall stage. While his vocals still retain the histrionics, and the between-song banter is chock full of pretentious twattery, the minimalist accompaniment limits how bombastic the performances can be. The results are probably closest to his solo debut (and still best solo album) Heartbreaker. He may be the singer/songwriter you hate to love, but the best of his talents are pushed to the forefront here. Surely one of his very best solo records.

Ryan Bingham – Fear and Saturday Night

Ryan Bingham – Fear and Saturday Night Hump Head HUMP171 (2015)

Sounds a lot like the determined gruffness of John Prine and the rock-tinged country of later-period Lucinda Williams, but with more affinity for classic rock. Bingham is a fair songwriter, though his gravelly voice sometimes comes up a bit short on range and nuance. Still, this is what more country music should aim for.

Japhy Wilson – The Joy of Inequality

Link to an article by Japhy Wilson:

“The Joy of Inequality: The Libidinal Economy of Compassionate Consumerism”

Bonus links: “The Politics of Online Friendship” and “So You’re Still Being Publicly Shamed” and “Too Much of Not Enough: An Interview with Alenka Zupančič”

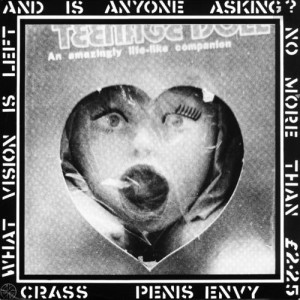

Crass – Penis Envy

Crass – Penis Envy Crass Records 321984/1 (1981)

Crass delivered their finest studio album with Penis Envy, though the album set in motion the forces that would eventually dissolve the band. Later faced with obscenity charges, for this album and others, the legal battle to eventually beat most of those charges (except for the song “Bata Motel”) put a strain on the group they couldn’t really survive — their decision to disband in 1984 also coincided with supposedly earlier plans to call it quits after a few years. Though really by the mid 1980s the punk movement had dissipated and the legal troubles, changes in personal outlook and interpersonal frictions amongst members almost seem like convenient excuses for the band to call it quits. Still, the essence of Penis Envy is a classic punk dare: mocking the powerful to provoke them to show their impotence and powerlessness to prevent the mockery. Sure, the lawsuit left the band with some wounds, but the music survived, to embolden anyone who hears it.

The subject matter of the songs is decidedly feminist. The album title refers to Sigmund Freud‘s theory of female sexuality, a concept that has been criticized — as recounted in The Story of Crass drummer Penny Rimbaud called it “one of Freud’s more absurd theories” in a 1983 interview — but in some ways aspects were rehabilitated by Jacques Lacan‘s way of symbolizing jouissance that saw “penis envy” as just a signifier of a fundemental lack (among many other signifiers of lack) and giving women greater awareness and choice in such matters than men. The song “Where Next Columbus?” invokes C.G. Jung, and goes so far as to critique medical profiteering — “You’re not yourself, the theory says / But I can help, your complex pays / Another’s hope, another’s game / Another’s loss, another’s gain.” With all the other thinkers mentioned in the song, the song suggests the limits of ideas and intentions, and that even the greatest thinkers can’t stop others from using their work for repressive control, and to amass power for nefarious, self-serving purposes. Or maybe it is just a contrarian slam against famous intellectuals of all sorts. All that aside, Crass can invoke the term “penis envy” to critique patriarchy.

The opener, “Bata Motel,” offers a first-person account of a submissive, oppressed, hyper-sexualized woman. The premise of the song is to make male fantasies seem crude and horrible, building the case that those perpetuating such treatment of women should feel guilt.

Most of lyrics avoid casting blame on individuals. For instance, “Systematic Death” is an indictment of exploitative systems, such as patriarchy and capitalism.

“Our Wedding” was given away as a flexi-disc (cheap 45 RPM recordings on flexible square sheets) with the magazine Loving as a prank — credited to Creative Recording And Sound Services (which translates to the acronym CRASS). It was tacked on to Penis Envy. The song itself is a parody of sappy music. Though it is also not a bad song.

A big part of what makes Penis Envy so great is the musicianship. Eve Libertine handles most of the vocals, with Joy de Vivre singing one song (“Health Surface”). Libertine is a more versatile and adept vocalist than Steve Ignorant, Crass’ primary vocalist who does not appear on the album. Drummer Penny Rimbaud is able to summon lilting military march sounds, jazzy fills, and itinerant punk rumbles. There are heavy bass lines here, from Pete Wright, that are fairly prominent in the recording mix. The guitars (Phil Free and B.A.Nana [AKA N.A. Palmer]) noodle around, usually in an icy, brittle, high treble range, never quite assuming a dominant role. It is the very deferential stance of the musicians, true to their anarchist political roots, that refuses to privilege any one performer or part above the others. Yet the focus and structure on Penis Envy advances the music further than the sort of chaotic, same-sounding fury of most stereotypical anarcho-punk.

There is a thing about an “anarchistic” approach to music making. When the musicians simply play whatever they want, with only the loosest sense of pre-planning, the process of making the music may avoid exploitation of the musicians, but the results can put a heavy burden on listeners to make sense of something that presents no clear meaning. On the one hand, there is an attempt to avoid imposing beliefs on a listener, who can make his or her own meaning. But the real catch is that musicians cross a line, of sorts, when they actually go about recording and releasing such material, which strips them of any claim of being completely above or apart from coercive imposition of meaning on the listener. This is a tricky issue, and there is no right or wrong level of demands upon a listener. The band is sometimes criticized for putting too many demands on the listener with their later works, like Yes Sir, I Will (1983). But Penis Envy is probably the most coherent (and melodic) of all of Crass’ full-length albums. There is much more focus and deliberate songwriting on Penis Envy than earlier (or later) Crass recordings. There are some similarities to Lora Logic‘s band Essential Logic. Though, surprisingly, on these recordings Crass seems less improvised and less experimental.

To get into Crass, typically, listeners have to be willing to be (righteously) angry. Most of their music is built around takedowns of hypocrites and evildoers. They pointed a lot of fingers. They could get away with it because they lived up to their ideals more than the next band. Still, this wasn’t for everyone. Penis Envy doesn’t come across quite the same way, though. The approach is more bait-and-switch. They try to put forward concepts that are kind of widely accepted, then they render those concepts problematic. Decades later, this still holds up as something that pushes all the right buttons and pushes in the right direction toward a better world.