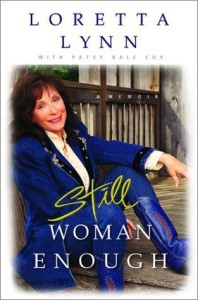

Loretta Lynn with Patsi Bale Cox – Still Woman Enough: A Memoir (Thorndike Press, 2002)

Loretta Lynn’s second memoir fills in a few gaps from her first, Coal Miner’s Daughter (1977), and picks up the years since that first book. This isn’t an autobiography that attempts to chronicle her entire life. It is episodic, jumping from one story to the next, revealing only as much as Lynn wishes. At times, that is the biggest limitation of the book. When she has something nice to say about someone, they are mentioned by name. When she has something negative to say about a person or band or business, she typically withholds the proper name. This is somewhat common with country music memoirs (Cash: The Autobiography does a little of the same, for instance). But the strength of the book is Lynn’s willingness to accept herself as she is without letting shame or embarrassment get in the way — at one point she acknowledges that she doesn’t read well.

The bulk of the book is devoted to explaining her relationship with her husband, known by his nicknames Doolittle and Mooney. As much as her music creates a persona of an independent woman, she stuck with Doo since her marriage at age thirteen, in spite of his philandering, alcoholism, abusiveness, jealousy, male chauvinism, and general craziness. She also writes a lot about the rest of her family, including her many children. There are maybe two pages total devoted to recordings, a larger number devoted to descriptions of live performances, and substantially more to the grind and crazy escapades of touring and being in the cutthroat entertainment industry.

Loretta Lynn’s best quality was her earnestness and total lack of guile. This shone through her music brilliantly. This memoir captures that same aspect, though at the same time her naivety comes through too, and it is hard to accept her frequently superficial explanations on a few topics, some of which veer into supernatural explanations. One such problem is that while she (rightly) takes some credit for being a pioneering businesswoman in the music industry, taking more control over her music than “girl singers” were usually permitted in the misogynist Nashville music machine, she has no grasp whatsoever of broader social forces. So she never quite gets around to offering any explicit context for how the three decade “golden years” of the working class coincided with her rise to fame. If you want that analysis you will need to look for a biography. But she still has plenty of great stories that revolve around her likeable bewilderment. For instance, she talks about being on a Dean Martin celebrity roast and leaning over during the taping to ask Martin when dinner will be served — she thought the event was really a dinner where celebrities get together and (literally) eat a pot roast.

I was reading this on an airplane and a steward leaned over and asked what it was, then — after saying he admired Loretta Lynn too — jokingly suggested that maybe I should put it in a paper bag so no one could see it. The cover definitely markets this as a “woman’s” book, the kind promoted on daytime TV. No doubt, this is driven by emotional responses to difficult life circumstances. But anyway, it is a decent enough memoir though this will probably only be coherent if you have read her first memoir or have seen the (rather excellent) biopic Coal Miner’s Daughter (1980), which is mentioned many, many times.

“For the October Revolution our class produced a small play in which a group of young Pioneers expelled the heroes of Russian fairy tales as ‘non-Soviet elements’. The curtain opened on this drab little group of Pioneers. Their appearance brought no response from the audience. Then the group leader . . . got up and made an introductory speech. She explained that the old fairy tales, about princes and princesses, exploiters of simple folk, were unfit for Soviet children. As for fairies and Father Frost [~Father Christmas/Santa Claus], they were simply myths created to fool children.