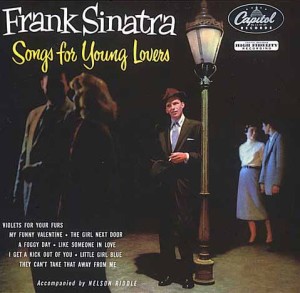

Frank Sinatra – Songs for Young Lovers Capitol H-488 (1954)

Sinatra was the perfect representative for the American WWII generation. In the 1940s, he had a somewhat frail and scrappy voice, capable of sounding very vulnerable and unsure. He sang many maudlin pop songs. By the 1950s, that all changed. His voice was more confident and debonair, with a cocky sense of swing. He recorded more music with jazzy arrangements. Songs for Young Lovers is Sinatra accomplishing his aims flawlessly. All of these songs are great. The album as a whole conveys a sense of contentment, a “top-of-the-world” feeling that is unshakable. Of course, in the aftermath of WWII, American geopolitical power peaked in the early 1950s (1951 to be exact), and the country was well into a period of unparalleled prosperity that would stretch out until the early 1970s, when Europe had rebuilt and the Third World started to fight against and (partly) overcome legacies of imperialism.

Nelson Riddle provides the arrangements and conducts. Although there are horns, strings and a jazz combo rhythm section, the accompaniment conveys a large and full sound with relatively few performers. It helps that almost every song has slightly different instrumentation, from electric guitar, to harp, to saxophone, to violins, piano…it is all here. The jazz treatments aren’t innovative. They take the best of what the genre had achieved over the last decade and distils it to a highly potent elixir. Sinatra, for his part, is just perfectly matched to the music. While the vocals and accompaniment do complement each other, Sinatra always finds ways to capture a listener’s attention with a whole range of techniques from brash vocal gymnastics to subtly nuanced shadings, while maintaining an impeccable sense of balance. He can change up his approach in an instant. In lesser hands this would come across as arrogant posturing. For Sinatra, though, it just seems like part of a world of limitless possibilities.

The legendary jazz trumpeter and bandleader Miles Davis credited Sinatra’s singing (and Orson Welles‘ speaking voice) as being a big influence on his own playing. Davis was onto something. Sinatra, at least on an album like Songs for Young Lovers, absolutely commands attention. This is a master class on how to be a star soloist. For every riff the band offers Sinatra has one more move to offer. The band leads, in a sense, yet Sinatra operates by his own rules and always pushes things further. Each step comes across as effortless. The effect is that his voice is unstoppable without ever being forceful, angry or merely loud. Maybe he had no basis for this confidence, or was overestimating his own personal independence (never acknowledging the structural social factors that made it possible for Sinatra to sing this way, unlike, say, the European songstress Lotte Lenya on her Lotte Lenya singt Kurt Weill of the following year that relied upon a fractured, scrappy elegance), but Sinatra never once flinches and he can convince just about anyone that this is the best pop music around. Take “The Girl Next Door,” with a part near the end in which a single violin plays a tremolo, like what accompanies silent movies in a sentimental scene with one character longing for another, supported by a gentle run on a harp, in which Sinatra comes in and calmly holds some notes to melt away the sentimentality. He follows that song with a solid, sturdy yet smooth delivery of “Foggy Day.”

For clear-eyed delivery, Sinatra was never better. No doubt, one of his best.