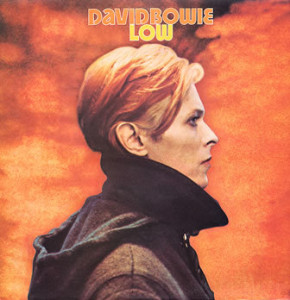

David Bowie – Low RCA Victor PL 12030 (1977)

CAN’s Tago Mago — half full-bore rock half ambient soundscapes — sketches the outlines of Low but this album sounds like no other. It represents is the beginning of Bowie’s “Berlin” period, the creative peak of his long and distinguished career. He made this album as a work of art. It is invigorating to hear someone not content to merely accept the confines of tradition, but try to work out new expression.

Even with its experimentation and avant-gardism, Low is always a pop record. David Bowie always had a flair for the dramatic. Here, his bold use of space and inverted compositions are a different kind of showiness. Bowie’s audacious attitude has purpose. He crafts Low like an artist burning inside.

Brian Eno is a major contributor to Low. He is the perfect foil for Bowie, and side two wouldn’t be the same without Eno’s presence. Even Iggy Pop appears for some backing vocals. Bowie was a major force in Iggy’s solo breakout The Idiot where he began honing the techniques employed here.

While there are some singles that came off the album, the full impact of Low comes on slowly. Deeply textured sounds present themselves with time. Bowie presents himself as an observer but one who’s objectivity has dissolved. His style is reflective of personal discovery. He becomes a part of his songs, and seemingly a part of a barren landscape.

“Be My Wife” is a dense number with pounding lines from the piano, electric washes of guitar and electronically process drum beats. There are few lyrics. An older Bowie comes to accept what he probably has known all along. The music lilts with his carefree pining but swells in gripping climaxes. The rhythm hesitates for each word. The jarring dynamics play into the compositions. They highlight but also mislead. There is simply too much to take in at once, so each time you listen there is another way to hear the songs.

Funky plastic soul (Neu!-beat really) from side one gives way to bleak anti-rock sound collages of side two. “Warszawa” is the centerpiece of the second side. Stark harmonies and unconventional melodies cast a sorrowful shadow on post WWII Europe. Bowie sings a few sounds, then stops as if he can’t go any further. It gets pretty intense. The music is still enjoyable, despite the grim realities lurking around every corner. Europe, of course, has a deeper connection to Euro-classical than anywhere else. Rock and roll is foreign. It makes sense than rock musicians in (of from) Europe have pulled the two together most spectacularly.

Bowie has been called a Warholian manipulator of surfaces. There is some truth to that, but Low could crush you under its weight. On a very basic level, Low maintains the essence of Bowie’s work in adapting broad concepts into his new music. His compositions use chunks much bigger than individual “notes.” Low, through Bowie’s own grammar, painted the perfect picture of a divided Europe. His determination is like a snowplow on some isolated mountain road. There is the risk of becoming stranded in unfamiliar territory but a greater purpose drives him forward. He has purpose, which makes his efforts so enduring.

Low is not just entertaining, it tells us something pure and unassailable about the bleak world from which it came — it evolved from Bowie’s role playing an alien who comes to Earth to save his home planet but gets lost in aimless hedonism in the Nicolas Roeg film The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976). Low is about a change of direction. That change isn’t inherently for the better. Still, the album is the very embodiment of artistic renewal, and so it is both enlightening and inspiring.