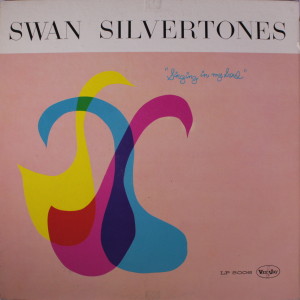

Swan Silvertones – Singing in My Soul Vee-Jay LP 5006 (1960)

For those not in the know, The Swan Silvertones were a long-lived gospel group — one of the best. Their second LP, Singing in My Soul, is perhaps their very best. The group had already been around for more than two decades when they made the album, an existence that pre-dated the album format era. Their early days involved radio performances (no recordings of those performances have been released). They then recorded a host of singles for the King label in the 1940s, which were mostly a cappella, with occasional acoustic guitar accompaniment. The group complained that the record label forced them to play up a kind of hillbilly, folky sound. Into the 1950s, they recorded “hard” gospel for Specialty records. All the Specialty sides are essential. The group sang searing leads, balanced with ravaged screams and driving tempos. Lead singer Claude Jeter made pioneering use of his falsetto range, seemlessly jumping between his natural range and his falsetto.

When the group moved to Vee-Jay records in the late 1950s — where almost all of the top gospel acts of the day recorded — there was a profound shift in their music. Instrumental accompaniment was much more pronounced, and varied. Vocals remained the focus. But there were new opportunities for interplay between vocal and non-vocal sonorities. On record they were paired with some of the finest session players around (in particular, the jazz group MJT+3), with credentials from outside the gospel world, because Vee-Jay was also active making successful recordings in other genres like blues and jazz.

Vee-Jay was a significant independent record label in its day, and was notable for being an African-American owned and operated company when Jim Crow segregation laws were still prevalent. It maintained a measure of dominance in the African-American market until overtaken by Motown, and Vee-Jay’s eventual bankruptcy due to financial mismanagement in 1966. Though, it should be noted, the label’s biggest commercial successes came not from black acts but from white acts like The Four Seasons and licensed state-side re-issues of recordings by The Beatles. Vivian Carter Bracken, one of the label’s owners, was a radio DJ first in Chicago and then in Indiana. Her knowledge and connections, not to mention her exposure on radio broadcasts, seemed to give her an edge identifying new talent and understanding commercial markets for music. Scores of major musical artists made their first commercially successful recordings for the label.

The opener on Singing in My Soul is the traditional “Swing Low.” The first sounds are from an electric guitar (from Linwood Hargrove), slowly playing two dissonant, descending chords. Louis Johnson, who joined the group about five years earlier, is the first singer heard, and he is sermonizing rather than singing as such, recanting a nostalgic tale about supposedly hearing about the lyrics of the song from “an old gray-haired lady” many years ago, presumably in childhood. A vocal harmony is introduced, with slow, wordless “wooos” filling out the space behind Johnson. Claude Jeter comes in next. He goes immediately to his falsetto range. He dips into his natural range briefly, only to swoop immediately back up to his falsetto. Some lightly brushed percussion on a cymbal (from Walter Perkins), and a faintly plucked acoustic bass enter in too (from Bob Cranshaw). As all this builds, there is a bluesy, jazzy approach to the instrumental accompaniment, though except for Jeter’s vocals everything stays respectfully in the background. There is actually a lot happening, with six or seven performers backing Jeter at the same time, yet the song still provides a sense of space and openness.

The next song, “Move Somewhere,” again opens with Louis Johnson. This time, though, he’s actually singing. His range is much lower and, frankly, narrower than Jeter’s, with a gravelly texture that is accentuated with slightly cracking, subdued screams used for emphasis. This song picks up the tempo. The full drum kit is used to provide syncopation. Meanwhile, the vocal harmonies introduce words, and the guitar continues in what seem like improvised blues/jazz riffs not far off from West Coast cool jazz of the latter part of the 1950s.

By the third song, “Lord Today,” Claude Jeter’s opening lead is ready to fully open up. His finesse in going from a robust use of his natural tenor range, with more limited, precise and dramatic forays into falsetto puts superb technical skill into play in the most friendly, welcoming way possible. Louis Johnson enters and he is now wound up to a more fevered pitch, pushing against the steady tempo of a rhythm section that is providing more forceful beats.

The first part of the album lacks any prominent contributions from the great Paul Owens. This changes somewhat in the middle and latter part of the album. Owen’s biggest chance to shine is on the closer “Stand Up and Testify.” The presence of a jazz trio kind of takes away opportunities for Owens to showcase his style of singing influenced by what was then fairly contemporary and modern vocal jazz. But he gets to do some of that in at least in that one song.

The group’s classic “Trouble In My Way” is re-recorded here with a brand new arrangement that manages to impress even with a completely different sound. Owens gets some time out front here, along with Louis Johnson. The backing vocals adopt something approaching New Orleans second-line music (with echos of “Jesus on the Main Line”). The guitar strums steadily in nearly a fury, setting aside the jazzy chords for the first time to play in a more incongruous folk music style.

As usual, baritone singer John H. Myles and bass singer William Connor stay pretty much out of the spotlight. What is more unusual, though, is that the group’s most talented arranger, Myles, isn’t felt so strongly on this album as on others. The jazz trio providing instrumental accompaniment is given relatively free reign to create a lightly improvised foundation, and the most of the backing vocals are straightforward call-and-response stuff. More complicated vocal treatments do come on the title track, with the instrumentalists holding back a bit more and the singers providing a more layers that more somewhat more independently, with solos from Jeter very nearly taking the role of the responses to the calls from the other singers.

“Near the Cross, Pt. 2” might well be a live recording. The instrumentalists can barely be heard, and there are shouts and handclaps that might be from an audience. Along with “Rock My Soul,” it raises the intensity and energy level of the album and helps provide a more a more varied song sequence.

This is my favorite Swan Silvertones full-length album. While it somewhat paradoxically gives over a lot of attention to the instrumental accompaniment, and the vocal arrangements are rather more straightforward than elsewhere, this holds together so well I can’t help but want to listen to it more frequently than most of the group’s original albums. It has a consistency of sound, yet it still maintains a kind of looseness and leaves room to sprinkle through it a variety of attitudes, tempos and phrasings that prevent stagnation down any single stylistic avenue. It may lack any individual standout songs, but the sum ends up being greater than its parts. The Swan Silvertones are definitely number one on my list of “greatest bands no one seems to have heard of”. Listen in!