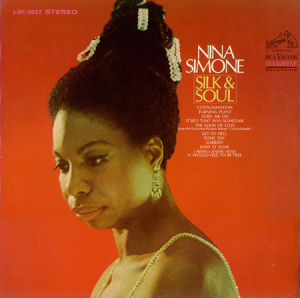

Nina Simone – Silk & Soul RCA Victor LSP 3837 (1967)

Nina Simone was an icon. She was dubbed the “high priestess of soul” by her fans, but they did so long before she actually started performing “soul” music. It was only in the late 1960s, a full decade into her professional career, that she made a foray into the genre. Frankly, this was one of her least convincing styles. She often came across as a huge stiff. She used formalistic vibrato (“Consummation”) in place of guttural drive, and pre-soul R&B shouting (“It Be’s That Way Sometime”) when a more supple delivery seemed advisable. In some ways, it is the mark of arrogance. She’s a philistine when it comes to soul music, but her hubris pushes her onward into territory that is slightly outside her natural stylistic range.

“Soul” was an afro-american musical form that often used “masking”, a technique that concealed social or political messages behind music that seemed on the surface to be (only) about romance, or whatever. The psychological issues of inferiority looming behind the technique are the sort of things Frantz Fanon wrote about in Black Skin, White Masks [Peau noire, masques blanc] (1952). When Nina Simone started making “soul” music, she frequently did it without masking. She sang soul songs that were directly about social and political issues–like her 1969 hit single “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.” The problem this presented is that it really isn’t possible to directly address any subject that really matters. There is a need to engender meaning from oblique angles. At least, this is what everyone in the structuralist or post-structuralist camp from Roland Barthes to Slavoj Žižek would say, in one form or another. So while the militant social activist Simone did address the problem Fanon identified, she kind of missed another issue. Even without the “white mask” problem, there is still no way to directly express something real without inscribing it on something else, another mask. Her mid-1960s recordings that had a more traditional pop or Broadway sound gave her a mask on which she inscribed something else. It is that something else that is often missing here. We get Nina Simone singing soul, but not Nina Simone singing soul as a unique way to tell us something else. She stops short.

On “Love O’ Love” we have just her on piano, a setting closer to her earlier work, which works, and it is the best thing here. In other places, “It Be’s That Way Sometime,” “Cherish,” “Some Say,” she’s out of sync with the backing band or the horns simply sound like dinner theater pop more than “authentic” soul or her vocals seem too flat and lacking texture that the greasy rock backing calls for.

Silk & Soul sounds more like a clinical, scientific experiment than the real deal. Simone was clearly trying to stay relevant by catering to what she (or handlers) thought audiences wanted, rather than making the sort of music that compelled her and trying to bring audiences to that, whatever it was. While not terrible, this is among Simone’s most forgettable albums of the 60s.