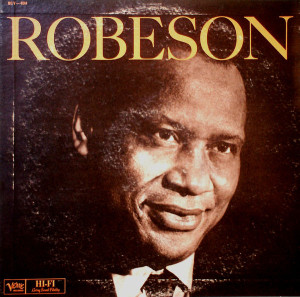

Paul Robeson – Robeson Verve MG V-4044 (1960)

You can’t find an American better than Paul Robeson. There are a lot of things life can throw at a person. You would have to say that Robeson encountered a good many of them and, in the face of those challenges, made the right choices no matter the burden of doing so (at least in his public life). Best known for his definitive performance of “Ol’ Man River” from the musical Show Boat, Robeson’s staggering list of lifetime achievements included being an all-American athlete, attorney, star of stage, screen and recordings, and internationally recognized civil rights activist. He took a principled stand in favor of the USSR, and as a result was harassed and persecuted over a period of decades by the U.S. government (the same government that tacitly permitted lynchings into the 1960s [with President Truman refusing Robeson’s challenge to formally ban lynchings by law] and to this day has a national holiday honoring the genocidal plunderer Christopher Columbus, the last man to discover the “new world”).

Robeson (Verve) was recorded August 22, 1960 in London. It was during a time when Roberson’s health was starting to deteriorate. His passport was revoked and he was denied international travel from 1950-58. But after the U.S. State Department reinstated his passport — and then only when forced to by the U.S. Supreme Court after the case Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116 (1958), a decision written by Robeson’s law school classmate William O. Douglas — Robeson resumed travel and revived his international performing career. That allowed him to make these recordings abroad. For his age, and given his health problems, his bass-baritone voice was still commanding. Though it had lowered somewhat, the vibrato a little shakier at times. While he sometimes performed “spirituals” (an early term for afro-american gospel music), this album features non-religious “pop” repertoire with orchestral backing. It was a return to pop for Robeson, who focused more on folk and activist material in the 1950s. Here, his voice is out front and the theatrically-leaning orchestral backing tastefully restrained. If ever a musical discussion turns to the question of the merits of lighter fare, turn to Robeson for proof that a great singer can turn any material into something meaningful and lasting. Not only that, if in the final analysis the history of the 20th Century mostly bore out Hannah Arendt‘s dictum about “the banality of evil,” then Paul Robeson’s provides us with a crucial look at what it will take in the 21st Century to find the antidote.