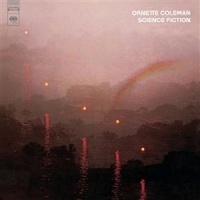

Ornette Coleman – Science Fiction Columbia KC 31061 (1972)

Science Fiction might be Ornette Coleman’s last really great album. It is a doozy.

In some respects, this is one of the last original statements of the musical approach Ornette had taken starting in the late 1950s. Many of these songs open with a “head” with two performers playing a composed line in dissonant unison. Then the songs open up with the performers playing in less coordinated ways. But that approach only accounts for a portion of the album, mostly in the middle part.

The opener “What Reason Could I Give?” is something different from the traditional Coleman song structure. Instead of a more structured head that gives way to less structured collective improvisation, the entire song is organized around unison playing. Every one of the performers, with some slight exception for the two drummers who must accept the more limited tonal palettes of drum kits in exchange for unobtrusively skittering rhythmic attacks, seems to be guided by a close and commonly structured composition that tries to balance the tone, volume and overall intensity of performance. A singer (Asha Puthli) provides an inherent focal point because of the lyrics, though really they are not “in front” of the other performers in any real way. This type of song structure seems like a more fully realized version of things Ornette had hinted at in the late 1960s, when he started working with Dewey Redman, but never really mastered. This song is fluid, engaging…convincing. And the balance never falters.

An open secret to Ornette’s music is the way he integrates composition and improvisation. Performers are not simply cut loose to play whatever they want. Ornette was a composer above all. Yet his way of composing presented the opportunity for his compositions to seem to dissolve away amid the improvisation. Paradoxically, the only way the improvisation can structure itself to overcome the compositional elements is through the compositions themselves.

So, starting with “Civilization Day,” Ornette is back to a kind of bop group combo formation that opens the song with a form of unison playing that leaves specific spaces in place. After the initial statement of the songs theme, the drums drop out, and then solos are traded. The bass (Charlie Haden) is very insistent throughout. It provides the strong urging of a regular beat that undercuts what would otherwise be an oppressive intensity from the wailing of the wind instruments. The next song “Street Woman” sort of combines the approaches of the first two. The bass takes more liberal departures from a steady beat, both in a rubbery statement in the head (plus a similar closing to the song), and in a prominent mid-song solo.

The title track launches straight into no-holds-barred skronking from basically the entire group, but then is overlaid with a heavily echo-processed spoken vocal recitation that is delivered as broken, almost independent declarations, bolstered by the sound of a baby crying. While the sudden presence of the vocals threatens to subordinate the skronking to a secondary role of just background noise, the disassociated nature of the spoken pieces, broken up further by the baby crying, deny those vocals the chance to take on the central focus of the song. Ornette uses misdirection. He structures the song to return to the premise built up by the first tracks just when the song seems to reject that premise. Its is a brilliant move.

“Rock the Clock” again opens right into a bunch of skronking from the wind instruments, but with Ornette on violin playing scratchy, abrasive and high-pitched bowed sounds, then an electric bass gives the song a touch of the sound of the jazz-rock fusion movement — very funky. Between the bass and the violin, two extremes sit together, taking opposite approaches (pulsed beats on bass, extended tones on violin) yet kind of create a meaning through their juxtaposition. This proves to be a great performance of a song that would become standard in the Coleman repertoire.

“All My Life” basically establishes the template for what Ornette would do with his Prime Time band in years to come. Puthli returns on vocals. However, this formulation lacks the immediacy of the opener “What Reason Could I Give?” Each performer seems to hold in place so as not to disturb the others. All together, nothing moves forward. It is as if the compositional framework amounts to no more than a very constrained set of rules governing how each performer must relate to the others (as to tone, volume and overall intensity). The content each performer delivers seems to get reduced to fluff — sort of like a theorist coming up with a complex mathematical equation to model some principle but working it through with only “easy” and unrealistic numbers to make the formula easier to compute. But “Law Years” ups the ante. It has a catchy hook, ending with a staccato “bah-doo-bah-da-doo-dah,” first introduced on Charlie Haden’s bass, that seems to stop short of a full resolution, like a person walking then suddenly stopping only to lean forward, through momentum, almost forcing this person to keep walking. The drums and bass pummel the listener with a drive that is unrelenting. It adds to the immediacy of the solos. The title “Law Years”, a kind of pun intimating “lawyers”, is sort of an aggressive challenge cloaked in a nostalgic look back at a bygone time of order. It is an expression of anti-legalism. Yet it is delivered through performances not too far off from what Ornette’s groups had been doing for a decade. This was just a more aggressive and militant expression of it.

The closer (“The Jungle Is a Skyscraper”) is sort of a throwaway, not really up to the rest of the album. It frequently verges on indistinct soloing without the conceptual force of the best songs before it. Ed Blackwell gets to pummel the drums a bit. But a lengthy drum solo doesn’t quite seem like the best way to cap an album like Science Fiction.