The Rolling Stones – Exile on Main ST Rolling Stones Records COC 69100 (1972)

A sprawling thing, Exile On Main ST runs through blues, county, gospel, soul and rock with reckless abandon. Exile is a stellar affirmation of American music, strangely enough coming from some boys from the U.K.

Most of the album writhes in murk (akin to Sly & the Family’s There’s A Riot Goin’ On). Jagger’s vocals sound muffled. Half the time you can’t hear a damn thing he sings. “I Just Want to See His Face” sounds like you stumbled onto some backwoods gospel revival tearing through what turns out to be an anti-gospel song. Jagger moans in front of some backup singers who scream passionately but seem caught on record only by chance. That mystique of careless luck gives Exile its grandeur. The entire album stays true to its desire for unrefined expression.

This is basically the most important Stones album. It would be hard to predict the Stones would have done anything in the 70s after they kicked founder Brian Jones out of the band (and Jones died shortly thereafter). Mick Taylor finds himself settled into the band, finally. His slide guitar works magic on the masterpiece of uncontrollable longing and charismatic bombast “All Down the Line.”

Backup singers belt out harmonies behind Jagger with horns blasting in a fever. Even Billy Preston stretches out for a guest spot on organ and piano on “Shine A Light.” Every piece of Exile comes together.

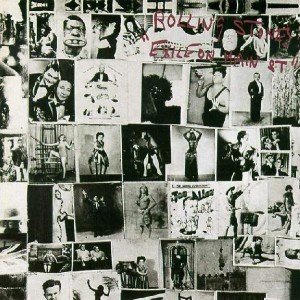

None of the individual songs achieved quite the popularity of earlier hits, like “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” because they are so uniformly brilliant. The album is still greater than the sum of its magnificent parts. Battered losers and hopeless wrecks parade through honky-tonks and the open road, holding on to what they can. Like the Fellini-esque Robert Frank photo collage on the album jacket, freaks stand placed in a precarious kind of order. When you see a song named “Soul Survivor,” you can hardly take the Stones’ word that they in fact “survived.” Rather, listening to the song reveals they barely made it this time (and may not the next). It’s easy to identify with the characters’ endless attempts to find compassion.

Rebellion is a prerequisite for rock and roll. The German artist Joseph Beuys said art is the science of freedom. In the Twentieth Century at least, the pursuit of freedom necessarily involved the rebel attitude so deeply ingrained in the fabric of rock and roll. The Rolling Stones certainly did their part. They always slid in some raunchy songs that chipped away at the establishment. “Loving Cup” and “Rocks Off” are sleazier tunes than they appear and reveal much more than idle ramblings of libertines. Their vices haunt them as they search for something to hold onto. They testify to the simple joys of common failures. You also have the deconstructionist spin of English boys redefining the musical traditions of another land. The Stones carried with the basic ideals of American music while they wandered into new territory.

An album of this breadth and consistency is a rare thing indeed. Exile is never too polished. It is at the same time familiar and new. It seems so real because the results are so fragile.