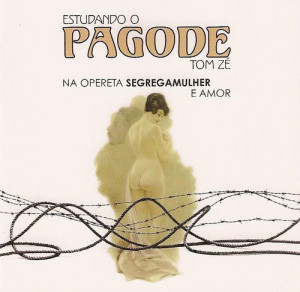

Tom Zé – Estudando o Pagode (Na Opereta Segregamulher e Amor) Trama 748-2 (2005)

Often described as a feminist operetta, Zé insists that Estudando o Pagode is not one. But he is merely explaining things so he can confuse you. If feminism is defined as the radical theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes, then this is absolutely a feminist work. The album was dedicated to philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft (author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792)), Isabella Faro de Oliveira, scientist Charles Darwin, ethologist/zoologist Konrad Lorenz and science journalist (and evolutionary psychology advocate) Robert Wright. The psychoanalyst Maria Rita Kehl is cited repeatedly in the libretto. A central concern is how the relationship between men and women is crafted in societies premised on domination and how hierarchies evolve and reproduce themselves, often in disguised and hidden ways. In an interview, Zé said,

“I would like to clarify a bit the general attitude of this album, an operetta about the woman situation.

“It is not a feminist work. Though it is not a machoist CD, it is, at least, ‘masculinist’: It calls man’s attention to the huge disadvantage he has created in his present relationship with women.

“A woman, nowadays, is slightly suspicious and cannot permit herself the easy-going kind of well-being of companionship that allows going from affection to a caress.

“Women have incorporated a feeling of mistrust towards men. She is always tense, worried, confronted with a potential enemy, an attitude created due to the psychological context of his situation in the society.”

This is a work meant for men, to convince them they have mistreated women throughout history to hold greater power. It is to convince men to see the world from a point of inclusive difference, not from a perspective of chauvinism. (Regarding the elimination of racism, Judith H. Katz wrote White Awareness from a similar premise: racism is a problem caused by white people and white people are responsible for ending it, not the victims of racism).

What Zé is really driving at is that this is not music premised on so-called “identity politics“. What does “identity politics” mean? In short, it is about building political power by looking at the world through identity, namely, by building groups having a common identity such as the same gender and then exerting the collective power of the group identity to achieve political ends, particularly from the perspective of so-called “minority influence” but also through coalitions. This is something promoted by the likes of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, and it has become one of the dominant aspects of neoliberalism — manifested through “inclusive” policies like multiculturalism.

French philosopher Alain Badiou is one of the most renowned opponents of “identity politics”. Badiou has said, “What is the world like when it is experienced, developed and lived from the point of view of difference and not identity? This is what I believe love to be.” If there is a way to relay the premise of Estudando o Pagode short of actually hearing it, this would be it. As acknowledged in the liner notes, following a lengthy quote/summary of Riane Eisler‘s book The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future (1987), Zé wants to push for utopian (gender) egalitarianism (using the past to break with the Gordian knot of the present with a form of argument that Walter Benjamin advanced: using the past to argue for a different future).

This music is also, thankfully, not really “opera” in terms of the manner of singing — it isn’t even bel canto popular music influenced by operatic forms of singing. American writer Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens) attended a performance of Richard Wagner‘s opera Parsifal and wrote a piece “Mark Twain at Bayreuth” in Chicago’s Daily Tribune newspaper, published December 6, 1891. He summed up a common reaction to experiencing a Wagner opera:

“The entire overture, long as it was, was played to a dark house with the curtain down. It was exquisite; it was delicious. But straightway thereafter, or course, came the singing, and it does seem to me that nothing can make a Wagner opera absolutely perfect and satisfactory to the untutored but to leave out the vocal parts. I wish I could see a Wagner opera done in pantomime once. *** Singing! It does seem the wrong name to apply to it. Strictly described, it is a practicing of difficult and unpleasant intervals, mainly. An ignorant person gets tired of listening to gymnastic intervals in the long run, no matter how pleasant they may be.”

The overriding reason that opera is sung in such an unnatural way is to emphasize distinction among its listeners and partisans. In other words, the very unnatural way about it, in relation to normal speaking voices, makes it esoteric and not readily appreciated. It takes time and effort (and resources) to cultivate an understanding of its objectives, and therefore involves a degree of “conspicuous waste” (to use Thorstein Veblen‘s term) that distinguishes the wealthy — who have time and money to cultivate obscure tastes — from the “rabble” — who don’t. Also, the “great person” aspect of operatic singing emphasizes that the feats of vocalization achieved by trained singers are not possible for everyone. This promotes inequality, and reinforces a sense that inequality is natural and just.

If the concept of a feminist (or masculinist) operetta still seems unappealing, know that this music is wonderfully quirky and idiosyncratic. Tom Zé is one of those endearing weirdos who can put a smile on the face of even the most bitter cynics.

This is the second of the (perhaps still-counting) trilogy of Zé’s “studies” (estudandos) of musical forms. The way he approaches these studies is reminiscent of Conlon Narcarrow, a major musical influence. Nancarrow composed (and recorded) “Studies for Player Piano,” punching holes in player piano rolls in way that produced music impossible for a single human performer to play. Sometimes he prepared the player pianos by rigging the piano hammers with leather or metal to produce different timbres, and synchronized multiple player pianos for performances in unison. Nancarrow’s works are intellectually curious and profound, while also being playful and having an affinity for popular musical forms like boogie-woogie (see his Study No. 3a for example, which, in the best possible way, sounds a bit like four pianists improvising on a James P. Johnson tune, simultaneously, as fast as they can play).

Zé uses a lot of different musical techniques here, drawn from many different quarters. The opening “Ave Dor Maria” features a processed, computer-like voice, reminiscent of Prince & The Revolution‘s “1999” (“Don’t worry, I won’t hurt you…”). The song draws on hip-hop and has a sturdy electric guitar-led rhythm. Many of the songs utilize electronically programmed sounds, for beats or just for noisy effects. “Teatro (Dom Quixote)” throws in anachronistic horns.

There is melody too. The Second Act in particular draws on pleasant lyrical statements, on “Eleau,” “Prazer Carnal” and songs around them.

Speaking about his talents — or lack of talent — he said,

“I am a very bad composer, a very bad singer, a very bad instrumentalist, but the text is the most important thing of everything. Because I am so bad, that is the reason I am here. I am always going to the edges where nobody wants to go and try to work it out.”

The studies albums are the most explicit in describing a process of working through problems at the edges of possibility. Syncretism has always been a part of Zé’s music. Yet here there are as many — or more — different types of music in one place as anywhere in his back catalog, and the mashups are both as dramatically incongruous and creatively provocative as they can be. This is also incredibly playful music. The themes may be intellectual, but the performances are approached almost like stand-up comedy. Tom Zé has always embraced compositions with disparate elements moving not in unison, but together, independently. There is much of that here: staccato guitar riffs and whistles, slowly moving washes of noise, tuneless glissandi caused by blowing on ficus leaves. There is a pervasive tension between lead and backing voices. They jostle. Zé calls these approaches “induced harmony” and likens them to “incipient practices” like he used as a child performing in the Brazilian folk genre of música sertaneja, and like the intuitive sociopolitical life strategies of ordinary people.

The story of the operetta is summarized on the back of the album. It vaguely resembles another strange psychoanalytic epic, El Topo. But don’t approach this thinking that following the libretto is crucial. It isn’t. The music is worthwhile on its own, even if you do not speak Portuguese.