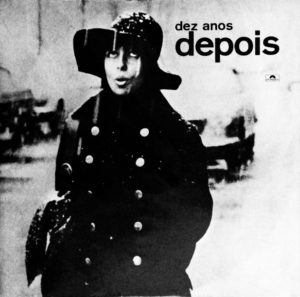

Nara Leão – Dez anos depois Polydor 2.388.004/5 (1971)

The history of bossa nova runs through Nara Leão, to the point that some claim the original bossa nova scene coalesced in her parents’ living room. She became a star in her native Brazil, and was one of the more popular bossa nova singers. But with the military coup, she first turned toward protest music, then left the country in 1969. She lived in Paris, and in August of 1969 announced in an interview that she had retired from professional singing. Her retirement proved short-lived. Soon enough she was back to recording and in 1971 released the double LP Dez anos depois, which featured new recordings of older bossa nova songs. The first LP was minimalist, and recorded in Paris. The second LP, only slightly less minimalist, featured some backing arrangements (by Roberto Menescal mostly, plus Luis Eça and Rogério Duprat for two tracks each), and was recorded in Rio.

Dez anos depois (translation: “ten years later”) is sort of a sister album to Françoise Hardy‘s La question (1971). Both have an intimate, melancholy feel, and expatriate Brazilian guitarist Tuca (Valeniza Zagni da Silva) appears on both. It might even be said that both put forward musical personas that were unique to the heyday second-wave feminism — not in terms of overt feminist militancy but instead (and somewhat paradoxically) by being unassuming thinking-woman’s music of a kind that simply wasn’t given much of an airing in prior times.

Tuca’s guitar is wonderful. Unlike the pure sublime gracefulness of João Gilberto or the sentimentality of Baden Powell, she leavens the angelic melodies with a hint of punky, plucky impertinence. “Fotographia” illustrates that point in its hypnotic strummed line unsettled by a dissonant, sour note lingering in the chords but never brought to the forefront. Across much of the first LP (seemingly the only disc on which Tuca appears) the melodic statements on guitar often seem rushed, almost, to emphasize the rhythmic aspects. This is both the essence of bossa nova, and a contrarian act of defiance.

Of course, Nara’s vocals are a big part of the album’s appeal. There is an insouciance to her delivery. The “ten years after” of the album title seems to refer to beginning her (then amateur) singing career that many years before. This is an album that looks back to a musical genre that she had left behind. But it looks back from a place and time in which Nara was living in Paris not long after the May 1968 student uprising came and went, and, in her own career, after a period of protest singing and retirement. So, rather than the cynical (anti-)flashiness of bossa nova in its early-/mid-1960s commercial peak, full of brash hope and revolutionary optimism thinly veiled behind leisurely tempos and sunny harmonies, Dez anos depois has a more deeply restrained and somber attitude, aware of the limitations of the first wave of bossa nova but still ready to draw on core elements that had weathered the intervening few years. That is to say that Nara’s renditions of these songs draw on the elements of bossa nova that precisely were not what garnered the music international success in the prior decade. This album makes attempts to find new meanings in the genre’s history. In that respect this album also does what any good “comeback” does: find something that was there before but overshadowed and emphasize it anew.

If much Brazilian music of the 1960s and 70s has maintained a cultish appeal internationally, thanks partly to limited geographic distribution of reissues in the CD era (and even the digital distribution era), Dez anos depois is somewhat doubly a dark horse given the timing of its original release and the superficial appearance as a mere recapitulation of the past. This is really an album that tries to right the wrongs of commercial bossa nova, giving the genre a new life of sorts. Even if the recording fidelity of the Paris sessions is only mediocre, this is an excellent collection of chamber-style bossa nova recordings from a surprisingly fertile period after the international commercial spotlight moved on to other genres, up there with Gilberto’s self-titled João Gilberto (1973) and Elis Regina and Antônio Carlos Jobim‘s Elis & Tom (1974).