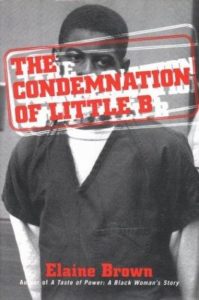

Elaine Brown – The Condemnation of Little B (Beacon Press 2002)

More than 15 years ago, Elaine Brown wrote a wonderful book named The Condemnation of Little B. It is both a sympathetic tale of Michel Lewis, known as “Little B,” who — when he was barely a teenager — was tried as an adult and convicted for a murder he most certainly did not commit, and a larger story of “New Age Racism” that explains why Little B’s individual story is, unfortunately, not all that unique.

The thrust of Brown’s analysis is conveyed by the way she recounts the prosecutor’s closing statement in Little B’s trial, which she says ended “with a dramatic flourish that revealed what the case against Little B was really about, about accommodating a powerful racist political socioeconomic agenda that at once invented and condemned black boys as superpredators.” (p. 336). This is part of the “New Age Racism” she describes, which is but an extension of old-fashioned racism:

“More than a century after the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, more than 130 years since the legal end of slavery, the black communities of the United States effectively formed a third world enclave of subcitizens within the confines of this richest nation in the world. Indeed, among the richest nations in the world, the United States, as the richest, maintained the highest poverty rate, with blacks at the bottom.” (p. 355).

Brown’s scope is sweeping. She manages to balance a sort of fast-paced “true crime” courtroom drama with a broader social science analysis of societal tends, as well as injecting the story of her own involvement investigating the case — while making that merely a framework to tell the story in an engaging way, without being a distraction from the real substance of the book. The book opens with a tale of how Brown became aware of Little B and the dominant media narrative about him, which leads into an explanation of how her research ended up debunking that narrative. She returns to Little B’s trial at the end of the book. Throughout, it is as if she repeatedly asks, “Qui bono? [to whose benefit?],” in analyzing Little B’s situation and the actions of all the players involved.

In the middle part of the book, she covers the politicians who grandstand about being “tough on crime” while being fully aware of the racially discriminatory purpose and effect of the policies they enact behind a wall of public denial and feigned ignorance. She covers the police and prison functionaries who viciously enforce degrading policies, careful not to question their own moral culpability in the process. She discusses how courts have failed to uphold principles of universal justice, for instance, ruling that plea bargains for witnesses are shielded from laws against bribing witnesses that on on their face would make prosecutors dealing them out felons. She discusses prosecutors repaying political supporters by engaging in witch hunts and duplicitous prosecutions — she even tells an anecdote about calling a prosecutor duplicitous to his face. She critiques lickspittle journalists of the so-called “fourth estate” who act as “an extension of the powerful” (p. 37) and who promote narratives that are contrary to fact but bolster the policies of ruling elites — others have called this a “propaganda model” or simply the media socially constructing phenomena. She calls out many who benefited from past affirmative action programs only to now kick the ladder away and deny others the benefits they themselves received. She also discusses how the United States’ “founding fathers” were unrepentant slave owners. In short, she portrays the larger context for how Little B’s story is the natural and intended consequence of the interrelated institutions of government, law enforcement, and society that today make up the politically dominant neoliberal program, itself a product of a top-down reassertion of power. And she names names. She never blinks in calling out by name the particular actors in Little B’s saga, or those on a regional or national level, even historical figures, who have acted to maintain systems of (racial) oppression.

The person who comes in her sights for the most criticism is undoubtedly former President Bill Clinton. There is a wealth of information here about Clinton’s duplicity, not only betraying campaign promises but ushering in the “New Age Racism” that Brown describes as a return to the Plessy v. Ferguson era. Central to this is the Clinton crime bill of 1994, which greatly expanded incarceration rates, predominantly among blacks, introduced severe mandatory sentencing, increased prison and law enforcement spending, and was an ignoble model for similarly severe state laws, combined with Clinton and Al Gore‘s legislative push (again an inspiration to states) to “end welfare as we know it.” For that matter this trend was just a continuing part of what Thomas Ferguson and Joel Rogers called a “Right Turn” in American politics. It is summed up well by the French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu‘s metaphor of “the left hand and the right hand of the state” — with the “left hand” social welfare programs starved of funds and the “right hand” (really, more of a right fist) coercive police and military institutions expanded — a metaphor explored in depth in by Loïc Wacquant‘s Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity, and echoing the “Pyrrhic Defeat” theory of Jeffrey Reiman‘s The Rich Get Richer and the Poor Get Prison, Katherine Beckett‘s Making Crime Pay: Law and Order in Contemporary American Politics, etc.

Brown’s research is astute and reliable. As one example, she even mentions government involvement in promoting drug trafficking in a way that acknowledges the still under-publicized and under-taught history of such activities. She also peers into the so-called “prison-industrial complex” to explain how private for-profit prisons need a supply of prisoners, and how manufacturing companies exploit forced convict labor. She peppers statistics throughout the book to support her arguments, without ever becoming bogged down in them. This is how readers know that during the 1990s, there was a 465.5% increase in the number of blacks imprisoned for drugs! (p. 352). And, at that, mostly for victimless nonviolent drug charges.

While much of her general historical analysis relies on Howard Zinn‘s A People’s History of the United States, a central part of her discussion of the “New Age Racism” of the people directly and indirectly involved in Little B’s case leans on Malcolm X‘s parable about the “field negro” and the “house negro”. (See pp. 209-212). Brown adopts the parallel terminology “New Age House Negros” — the contemporary version of Harriet Beecher Stowe‘s “Uncle Tom” character. Norman Kelley coined the derisive term The Head Negro in Charge Syndrome to describe the same phenomenon. This is very much the same concept that political economist Ruy Mauro Marini noted (the same year Malcolm X was assassinated) in relation to a “sub-imperialism” that involved peripheral economies (like the Brazilian junta) collaborating actively with the imperialist expansion of core economies (like the United States), assuming in that expansion the position of a key nation. It is also something Thomas Sankara, President of Burkina Faso, mentioned in his speech at the United Nations on October 4, 1984. For these “New Age House Negros” — Brown names people like Condoleezza Rice, Colin Powell, Clarence Thomas, William Julius Wilson, Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and others in this ignoble role — they are accepting personal benefits in exchange for betraying the larger cause of racial justice on a society-wide basis. It is worth quoting Brown at length here:

“More than merely advocating and sanctioning government policies that contributed to and maintained the wretched state of ghettoized and millions of other poor blacks, there had now come to be a new crop of Negros who, positioned to actually influence the outcome of government activity, were actively undermining the cause of improving the lot of blacks in America. Although their positions had been purchased with black blood in more than one hundred years of struggle, these new Negroes had become collaborators in a scheme that was imprisoning and further impoverishing more and more blacks. Given the moribund state of independent efforts by blacks for freedom, government policies and programs still represented the sole resort of blacks for redress and remedy for past harm, the sole relief and hope for the millions of Little Bs.” (p. 220).

These aren’t just blanket accusations. Brown goes into sufficient depth to identify precisely the positions publicly advocated, the benefits obtained, as well as contrasting examples for context. The people she criticizes generally deny these things, naturally, but Brown’s evidence in each case is more than adequate to convincingly show that these individuals got ahead by participating — as privileged collaborators and exceptions — to social systems of (racial) oppression. And she does that without leaning merely on a “Beautiful Soul” contradiction or the inadequate description of “tokenism”. Her position ends up close to that of Adolph Reed, Jr.‘s essay, “What Are the Drums Saying, Booker?: The Curious Role of the Black Public intellectual.”

A useful critique she offers in passing is of rapper Sean “P-Diddy” (formerly “Puff Daddy”) Combs, and the way his music’s message revolves around “a presumed conflict between the ‘player’ — a ghetto black who has gotten rich — and the resentment of the ‘player-hater’ — the black still stuck in the ghetto.” (p. 240). As a contrast, the TV show Good Times had a season two episode in 1975 called “The Debutante Ball” in which the protagonist Evans family, living in a public housing project, is confronted by the Robinson family, led by a father who became rich, left the ghetto, and wishes to sever all ties and connections to it — and hence does not want his daughter to attend a debutante ball with J.J. Evans, who is from the ghetto. Unlike Puff Daddy/P. Diddy, who sides with the “player”, the Good Times episode has sympathies in the other direction, accusing the rich man (“player”) of forgetting where he came from and suggesting that he is being anti-social and betraying necessary black solidarity. This regression is precisely the point Brown makes so well about “New Age Racism.”

When it comes to the discussion of Little B’s trial, Brown is critical of mistakes that his own lawyer made. Actually, she felt that the senior defense attorney was ineffective and Little B would have been better served by his less experienced but more competent co-defense counsel. In some instances, Brown has the benefit of hindsight. Yet there were still some rather glaring errors and oversights made. Those were compounded by a disinterested judge droning on in a monotone voice — something all too typical in criminal cases. But Brown spends ample time on the prosecutor, who used “emotionalism to cover the barrenness of facts” in the state’s case. (p. 327). In other words, she calls her out for utilizing a psychological persuasion trick that lowers public opinion of lawyers in general: like a magician using distraction to perform a sleight of hand illusion, the prosecutor makes an emotionally manipulative case that distracts from the cold impersonal evidence that leads to a different conclusion. Partly for this reason, some other countries use professional jurors, who can become more familiar with both courtroom procedure and tenth rate lawyer tricks, to perhaps see beyond them. For those interested, Brown does point a finger at the mostly likely murderer, a neighborhood drug dealer known as “Big E”, who avoided a life sentence on other charges as part of a deal with prosecutors to testify against Little B (the guilty party providing false testimony against another to avoid consequences is hardly unique to Little B).

While Brown’s book is about as thorough and well grounded as could be hoped, there are a few minor points where it might be improved. Brown frequently reproduces quotes using “[sic]” to highlight supposed errors. In at least a few cases there are no errors to be found, and Brown comes across as trying to shame the quoted speakers/writers in an exceptionally petty way. Cornell West gets dissed here, which may have been fair at the time of publication, but since Brown’s book was published West has changed his public positions in ways that would seemingly satisfy Brown. She also comes close to taking a very reductionist stance on racism, nearly divorcing it from other factors like economics, though she always pulls back from falling into that trap — resoundingly so with an MLK quote that closes the book. Still, much of her analysis of political ideology comes up a bit short in general, left mostly to implication, and might have been bolstered by citing to some other authors who have already developed similar lines of thinking. Adolph Reed, Jr. and Walter Benn Michaels come to mind. It also would have been interesting, if a digression, to have read Brown’s views on the argument that race is a social construct not supported by scientific genetics. Anyway, back on point, in the middle part of the book Brown criticizes “Enlightenment” era thinkers in a somewhat slipshod way. She lists many of the big names, and then criticizes most of them. But, for instance, she never gets around to debunking Jean-Jacques Rousseau on her list, which is curious because most of the framework of her book rests on concepts that run through Rousseau one way or another. It isn’t so much that her political/philosophical analysis is wrong as much as it is vague and undeveloped. Domenico Losurdo‘s Liberalism: A Counter-History was published after Brown’s book, which is too bad because it fills in the holes in Brown’s analysis in a perfectly complementary way. Losurdo argued that Liberalism is and always has been premised on the exclusion of some from enjoyment of its loudly self-professed support of freedoms and civil rights. He details at length how Liberalism has always advocated freedom while seeing no contradiction in supporting slavery at the same time — this being an essential aspect of Liberalism and not a deviation from it. Rather, Liberalism always places the maintenance of some form of social hierarchy, however softened or limited, above rights and freedoms. That is why the freedom that Liberalism promotes most strongly is ultimately only that of the unimpeded movement of economic capital. Brown is advocating for the universal applicability of personal freedom, seemingly free from the limits of hierarchy. This underscores something that is never explicitly stated in Brown’s book: she is really criticizing neoliberalism (the dominant strain of Liberalism at the time) from the left through the lens of one particular person’s story and the context behind it.

In this light, Brown’s book presents Little B’s case as a situation not terribly unlike the so-called “Dreyfus Affair” in Third Republic France a hundred years previous (1894-1906), in which an article by Émile Zola run under the iconic headline, “J’accuse!” publicized how the Jewish military captain Alfred Dreyfus was framed by military commanders. That case illustrates a political divide manifested through law enforcement and judicial proceedings. The basic split is between, on the one hand, those who believe that every person is equally entitled to a fair trial and that the innocent should never be punished for crimes they did not commit, and, on the other hand, those who believe in maintaining social institutions and traditions even at the cost of throwing a few innocent people in prison once and a while. The latter tend to evoke Plato‘s idea of a “noble lie” used by elites to sustain a society of their own design, and Kant‘s position that such lies must never be questioned or exposed or else the legal foundation of society will collapse. In this way, the people who throw innocents in prison often sincerely believe that they are doing good, even if they lie, plant evidence, deny access to an attorney, etc., because they are preserving a system that is necessary in their eyes — denying or concealing the essentially political choice involved in selecting a particular system in the first instance that puts some in power over others. Elaine Brown is of course on the former side, decrying the imprisonment and punishment of any innocent person, and, by extension, seeing corresponding change to existing social systems to equalize power relations as desperately needed and long overdue. Another reviewer put it well by writing, “She is witheringly good at exposing the myths that allow power groups, both black and white, to exploit and crush the weak with a comparatively untroubled conscience — all more or less veiled versions of racism, ranging from Jefferson‘s theories on why blacks can’t write poetry to today’s trumpeted ‘new phenomenon’ of young, black male ‘Superpredators’ sprouting in our midst.” Taking Losurdo’s analysis as a reference, this amounts to saying that the centrist neoliberals are, at a very fundamental level, actually more aligned with the conservative/reactionary right than they admit.

Brown does inject herself into the narrative, particularly in the very beginning and very end of the book. It is clear she rejects the so-called journalistic “ethics” of “non-involvement”, which can be questioned on moral grounds as being far too convenient for journalists. But her perspective adds to the story, and orients readers to the author’s perspective.

The Condemnation of Little B is a landmark. Unlike trashy, novelistic “true crime” books like Truman Capote‘s In Cold Blood, which epitomize an emotionalism that sidesteps the deeper moral questions about social constructs and institutions, Brown dissects and critiques those overlooked questions with surgical precision. It is remarkably comprehensive, always defends the moral high ground, and is relentless in questioning the legitimacy of social power structures. Hats off to Brown.

Michael Lewis, “Little B”, remains in prison: http://freelittleb.com/