Link to an article by John Molyneux:

Tag: Art

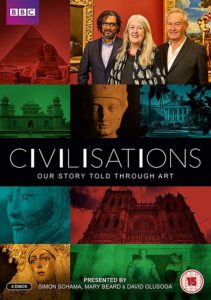

Civilisations

Civilisations [Civilizations] (2018)

BBC Two, PBS

Director: Tim Niel (possibly others)

Main Cast: Simon Schama, Mary Beard, David Olusoga, Liev Schreiber (USA version only)

The BBC produced an art history mini-series entitled Civilisations that reprised a series called Civilisation: A Personal View by Kenneth Clarke from decades earlier. The series title was spelled Civilizations for its modified version aired on PBS in the USA, in which different narration is used and possibly other changes were made. This review focuses on the version aired in the USA.

The early episodes discussing ancient civilizations written by Mary Beard are the best. They offer nuanced discussions of ancient art that has survived to the present, along with hypotheses about how the societies that produced that art were structured. The later, recent-era episodes written by Simon Schama and David Olusoga are troubling. Those later episodes engage in a politically reactionary “university discourse” (Jacques Lacan’s term) that sets up a highly reductionist (and biased) binary, which can fairly be called liberal blackmail: modern industrial capitalism vs. new age paganism. Scrupulously avoided in the series is any positive (or even neutral) depiction of art from communist countries or communist artists, or anarchist ones, which would allow viewers to see an alternative to both the art of industrial capitalism and the art of various indigenous cultures and remnant monarchies. If this absence of communist-leaning art seems accidental, it isn’t. There is one episode (written by Schama) in which a Chinese artist is profiled. Who was the Chinese artist? One condemned by the Chinese government and praised by the (anticommunist) West. It is a framing that overtly revels in highly partisan cold war politics. And when modernism is discussed, the focus is on innovations in the techniques of painters and in the selection of subjects for paintings (analyzed through a lens of liberal identity politics), ignoring, for instance, one of the founding works of modernism: Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” (1913) painting (a similar work from another, more recent artist without any connection to the former Soviet Union is instead featured in one episode, and in the final episode Piet Mondrian is discussed as the founder of modernism, a view contrary to that of numerous other art historians). The goal here is clear, and it is anti-communist propaganda in furtherance of political liberalism that benefits the bourgeoisie and reactionaries who want to “try to roll back the wheel of history.” (Because “the abstract and conceptual art of Malevich’s Black Square (1915) and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917), . . . tried to challenge the entirety of ‘bourgeois’ culture.”) As Hans Modrow has said, “Thomas Mann’s point of view is quite right: anticommunism is the disaster that creates this suffocating atmosphere which removes people’s ability to reason independently.”

My spouse was waiting for the show to profile the likes of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. But I knew the show would omit avowed communist artists like them. Kahlo and Rivera were in fact not featured in the series, nor were any artists remotely like them.

Viewers may gain much from watching the Mary Beard episodes but skipping the Schama and Olusoga ones and substituting, say, Sister Wendy’s Story of Painting (1996). Yes, a show hosted by a nun is less dogmatic and less biased than those by Schama and Olusoga! Another good supplement would perhaps be Ways of Seeing. Also, the original series by Kenneth Clarke is worth seeing, for the most part. Despite being exclusively focused on European art history, and despite Clarke’s off-putting neo-feudal advocacy and recurring anti-communist diatribes, he at least openly called himself in the series a “stick-in-the-mud” advocating outtdated political ideas, which is something that Schama and Olusoga are shamefully unwilling to do in this later series.

Daniel Lopez – The Conversion of Georg Lukács

Link to an article by Daniel Lopez:

John Steppling – The Dying Light

Link to an article by John Steppling:

Bonus link: “The Wisdom of Serpents” (see also “Sorry, Bernie, We Need Radical Change”)

John Berger – The Primitive and the Professional Quote

“The distinction between profession and craft is at first difficult to make, yet it is of great importance. The craftsman survives so long as the standards for judging his work are shared by different classes. The professional appears when it is necessary for the craftsman to leave his class and ’emigrate’ to the ruling class, whose standards of judgement [sic] are different.”

John Berger, “The Primitive and the Professional,” New Society 1976 (reprinted in About Looking).

Ross Wolfe – About Two Squares

Link to an article by Ross Wolfe:

“About Two Squares: El Lissitzky’s 1922 Suprematist Picture Book for Kids”

John Berger – Art and Property Now

Link to essays by John Berger:

from Landscapes

“Defending Picasso’s Late Work”

Bonus links: Ways of Seeing and Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste

Frances Stonor Saunders – Modern Art Was CIA “Weapon”

Link to an article by Frances Stonor Saunders:

Bonus Links: “How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War” and Who Paid the Piper?: the CIA and the Cultural Cold War and The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters and Archives of Authority: Empire, Culture, and the Cold War and The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America and Satchmo Blows up the World: Jazz Ambassadors Play the Cold War and Dance for Export: Cultural Diplomacy and the Cold War and Cold War Modernists: Art, Literature, and American Cultural Diplomacy and Music in America’s Cold War Diplomacy and Jazz Diplomacy: Promoting America in the Cold War Era and Fall-Out Shelters for the Human Spirit: American Art and the Cold War and “Cold War Propagandist: Nicolas Nabokov, JFK, and the Shostakovich Wars” (much of this commentary is insipid, but some useful historical background is provided) and Finks: How the C.I.A. Tricked the World’s Best Writers and “The CIA Book Publishing Operations” and “Theaters of War: Hollywood in Bed with the Pentagon and the CIA” and Pulp Empire: The Secret History of Comic Book Imperialism and “Dangerous Melodies: Classical Music and US Foreign Policy in the 20th Century” and “From Fight the Power to Work for It: Chuck D, Public Enemy and How the CIA Neutralized Rap”

Some of the books above applaud the anti-communist propaganda that the CIA, State Department, and other U.S. institutions were pushing/funding, while others are more critical.

What is sort of most bizarre about all this is that the Soviets took the bait! That is, many people in the Soviet Union did believe they were falling behind the U.S. and western nations and their abstract art (etc.), as described in Moshe Lewin‘s The Soviet Century.