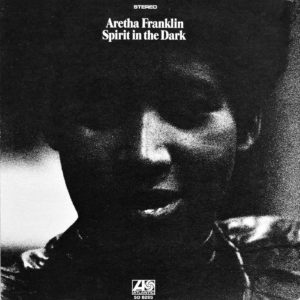

Aretha Franklin – Spirit in the Dark Atlantic SD 8265 (1970)

Admittedly, Aretha has never been among my most favorite soul singers. Don’t get me wrong, she is talented and all that. But I think I have finally pinpointed why she never made the top of my favorites list. Really, she was the epitome of liberal compromise in the late 1960s. She represented an ultimately quite fragile meeting of southern and northern elements. Her early career saw her trying to be a jazz singer of sorts, and she was never more than mediocre in that genre. That embodied her pretensions to “northern” culture, presumptively “sophisticated” (something akin to the impossibility of working-class achievement). When her career really took off, she was melding smooth, urban northern music — epitomized by being on Atlantic Records, headquartered in New York City — with southern soul out of the Otis Redding school, mediated by secularized gospel phrasing. If it is unclear why this translates into liberalism, the fact that she performed at both President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009 and President Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993 is all the confirmation required. Aretha invokes precisely the sort of “good on paper” liberal aspirations of Obama and Clinton, as a calculated invocation of movements and sub-genre styles already in existence to lay claim to some kind of triangulated coalition. For more circumstantial evidence, look to the way Malcolm X broke away from Aretha’s conservative-liberal father (Rev C.L. Franklin) in the mid-1960s precisely over the issue of compromise/collaboration — Malcolm labeled him a “clown”. I called this sort of liberal compromise “fragile” for good reason. Look at Aretha’s albums during her prime years on Atlantic and they are quite uneven. Some are clearly trying too hard to make obscure connections. The semi-flops (This Girl’s In Love With You) reveal how dependent she was on arrangements. Either Aretha had no sense when it came to putting together records, succeeding largely by dumb luck, or, more likely, she had little say in making albums or (most likely) was too easily convinced to engage in calculated appeals to “cross-over” demographics (“hey, do a version of this song that [insert social demographic here] is sure to like!”).

Spirit in the Dark from 1970 reflected changing times. Black militancy was peaking, but there were simultaneous efforts to accommodate establishment interests in exchange for favored status granted to a few token minority representatives. Which way would Aretha go? Eventually, it would be the latter. But on Spirit in the Dark she tried to stake out a middle ground. While her very best albums (I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, Lady Soul) have a deep sound, with prominent bass, organ, and horn sections anchored by saxophones, here the instruments behind her are much more of mid-range pitches. There is a lot of guitar, sometimes with a slight psychedelic edge. The bass is brighter than usual. Sporadic use of organ is buried in the mix, and tends toward higher-pitched stabs. The backing vocals are very orderly, sort-of “proper”, but still with a bit of homespun charm (read: imprecise coordination/synchronization). Gospel techniques are readily deployed, with a very, very light touch. Most importantly, though, Aretha really tries to belt things out when she sings, reaching rather than staying in a familiar comfort zone. “One Way Ticket” is a great example of that. I usually object to calling Aretha a powerful singer, because she drew a lot from gospel where powerful singers are called “housewreckers”. Put Aretha next to gospel icon Mahalia Jackson (perhaps the closest comparison in tone) and no one would point to Aretha as the more powerful singer. But purely on her own terms, Aretha does sing powerfully here.

Opinion is somewhat divided on this album. Fans of her late-1960s records sometimes see this as falling off in quality, if still a very good record. Others name this as one of her finest. To me, this is the last gasp of her relevance and up there with her best. This is one of the very last (chronologically speaking) southern soul album of note. In just a few short years, with a few notable exceptions like Al Green that prove the rule, almost everything would be “retro” or “neo” southern soul, lacking the kind of authenticity still present here — something cemented by the collapse of Stax Records in the near future. Granted, that authentic sound is hedged against what were clearly changing times, but that is partly why the authenticity remains. (Contrast Sly & The Family Stone‘s Heard Ya Missed Me, Well I’m Back, which might be a good example of a fake and inauthentic invocation of the past, ignoring changing circumstance). With Young, Gifted and Black Aretha would throw her lot in with what became known as “identity politics” — a kind of anti-politics based around fear of making offense — then Hey Now Hey (The Other Side of the Sky) would push her firmly into the gutter of commercial pandering from which she would scarcely escape. But here, Aretha makes an effort to change in order to stay the same. In other words, she adapts to the times in order to try to preserve a little something of the spark that made her very best stuff from the 60s great.