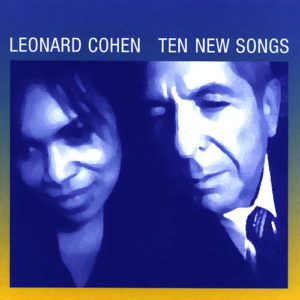

Leonard Cohen – Ten New Songs Columbia CK 85953 (2001)

“I fought against the bottle / but I had to do it drunk”

— “That Don’t Make It Junk”

Leonard Cohen, the beautiful loser, has endured as one of the most important lyricists in rock ‘n’ roll history. He has long been a patron of tortured souls. Yet, Cohen is adrift himself. He doesn’t speak from a sturdy pulpit but rather from intermittent places of shelter. Ten New Songs from 2001 was Cohen’s first studio recording since 1992. Acceptance overrides bravura in this glimpse of Leonard Cohen; but as always, his songs present an intelligent view of a complex existence.

The past decades have seen Cohen embark on a spiritual journey that prior to this album included about six years at a Zen retreat (where he took the name Jikan, “the Silent One”). It seems his journey provided at least some resolution. Ten New Songs returns to exploration of the tension of relationships where Cohen still seeks a love he knows he will never find. He has no answers to dispense, but speaks for lack of a better alternative. His voice barely hanging on (it is almost gratuitous to call him a “singer”), he now doles out oddly reassuring commentary from the shadows. In somber tones, Ten New Songs pulls together all the facets of his genius.

The first and last tracks are bright moments and instantly Cohen classics. On “In My Secret Life,” he grapples with a realization that his only actions lie in dreams. Cohen’s quest for truth yields to a hope for any understanding (as on “That Don’t Make It Junk”). His misery collects inside. He tries to make sense of the infinite textures of love and peace. Cohen’s spirituality is still alive in the simple prayers of “The Land of Plenty.” His words do provide, even if only for a moment, unthinkable possibility.

Sharon Robinson, who first worked with Cohen on his 1979 tour, performs the accompaniments almost entirely herself and co-wrote all the songs. She makes an opportune ally in these battles with pain and longing by tempering the fine line between Cohen’s soul and his gravelly monotone. The album cover illustrates, with both heads cocked to their right, the alignment of their thinking. “Alexandra Leaving” find the two in their finest form, singing a classic Cohen tale of fleeting love. Hopefully, Cohen could get by without a collaborator, which may show his continuing desire to utilize Robinson’s many contributions. Perhaps an older — and even wiser — Cohen seeks a compromise.

Leonard Cohen, with Sharon Robinson, has modestly made another album of solemnly dark beauty. His wretched existence continues to expand a legacy of brilliant works. Ten New Songs is a great collection of songs by any standard.