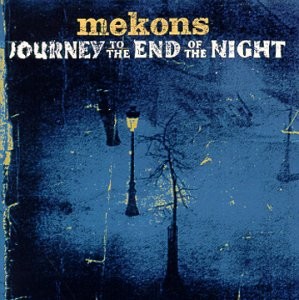

Mekons – Journey to the End of the Night Quarterstick QS60CD (2000)

When I was listening less than a week after Lou Reed died, I contemplated how Journey to the End of the Night (like much of Reed’s later work) represents middle-aged rock. Mekons bandmembers were in their 40s when they recorded this. It is tempered and softened like you might expect a rock album by middle aged persons to be. But it also has noisier guitar (“Cast No Shadows”) and harder meaning in the lyrics than the sort of “adult contemporary” or “dad rock” pabulum that is passed off as what mainstream rock audiences of comparable ages should listen to. But this is music with more substance than that, even when it draws some cues — and it certainly does — from those more insipid genres. Take one of the album’s best songs, “TINA”. It’s the acronym Margaret Thatcher’s brutal regime used to declare: “there is no alternative” to her political program (still in place as of this writing). By that she meant that her cronies in finance, who cast her in the role of “useful idiot”, were given free reign to run roughshod over the UK’s welfare state, selling off public assets for a fraction of their worth and terminating social programs, all to make the rich richer on the backs of the poor and working classes. But this song talks about how “it looks like an accident / caused by the government” but the singer can still say that “I can still dream of things / that have never been / but someday will be.” It’s an attempt to convey how there is indeed an alternative, with a human face, and it’s inevitable. This is the sort of stuff adults should care about, and here it is in a rock song with a light reggae beat. Rather than confining rock to the endless loop and infinite permutations of personal relationships — key amongst the famous compromises in “formal freedoms” granted after the 1968 uprisings–this is making the music about the political. Upping the ante, perhaps, is “Last Night on Earth,” which, if you can believe it, is about the origins of printed money. A few years after this album was released, anthropologist David Graeber published Debt: The First 5,000 Years, which explains how money in human society arose to replace moral debts (not to replace a barter system, as is mindlessly repeated by most orthodox economists). It tells the same story as this song. So this begins, “life is a debt / that must someday be paid.” That is the story of money. Note also that the liner insert for this CD features photos of the signs outside an exploitative check cashing business.

Hey, but all this talk of politics and economics doesn’t really hit you at all at first. The music sounds refined, acceptable. That’s what makes it special. The Mekons certainly have better albums. But with Journey to the End of the Night (sharing its title with Céline‘s best novel, «Voyage au bout de la nuit») they demonstrate a faculty with the most difficult of prospects, that of making rock and roll that is both mature and yet still rock and roll. It’s softened more than most, and unlike Lou Reed they take a few more shades off the driving guitar sound, leaving hardly a guitar solo to be found. Still, it’s all within the realm of rock. As I’ve said before, the concept of middle-aged rock is categorically rejected by many who feel rock is a young person’s game. I think it’s a difficult proposition, a narrow terrain prone to failure, but I think rock should be open-ended enough to allow it, and I think the concept can succeed. Journey to the End of the Night is such a minor success, not without its own flaws.