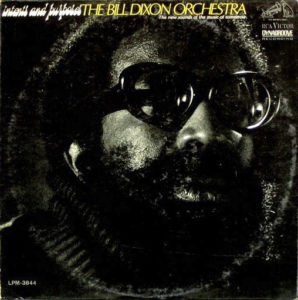

The Bill Dixon Orchestra – Intents and Purposes RCA Victor LSP-3844 (1967)

The 1960s represented a crucial period for jazz music, with its commercial appeal dropping precipitously, a host of radical new innovations developing, and recording technology reaching an important plateau of sorts. It was an era producing many acclaimed albums, with the album format in general coming into its own during the decade. But even among the many great jazz albums of the era, Intents and Purposes stands out. Bill Dixon was one of the great jazz artists of the 20th century, though for a variety of reasons his name is not particularly well known and his relatively small catalog of recordings has not consistently remained in print. That was somewhat the fate of Intents and Purposes.

Recorded with a large group orchestra, the music is able to realize a wide range of textures and produce rather large swings in dynamics. The pieces tend to, strangely enough, include many highly conventional elements of jazz and classical music. There are clear melodic statements, tightly choreographed harmonies, and even syncopated rhythms. But what makes the album so unique is that those conventional elements are a rather small part of the music as a whole. Dixon places an unusually large emphasis on timbre/texture, space, and compositional movement. There are frequently almost independent statements, such as a passage with a simultaneous trumpet improvisation, string harmonies, a pizzicato bassline, and skittering percussion, each of which might have stood on its own. The way Dixon puts these elements together largely eliminates distinctions between foreground and background. Filmmaker Robert Bresson famously said that while most people considered film the combination of theater and photography, he saw it as the combination of painting and music. With Dixon, he seems to make music that combines philosophy and (wordless) poetry.

It has been noted that Dixon drew substantial influence from the work of Ornette Coleman, whose unique style of composition and performance utilized motive structures (as described by Gunther Schuller in the liner notes to Ornette!). Dixon offers his own take on Coleman’s motivic development. It is fair — and perhaps appropriate — to call Intents and Purposes “harmolodic” music, after Coleman’s portmanteau term for his own artistic theory. Though Coleman tended to always emphasize elements of juxtaposition, while Dixon emphasizes synthesis a bit more. That is evident in how he merges foreground and background, eliminating soloist/accompaniment distinctions. There are also some resemblances here to “third stream” music, such as the collaborative album Jazz Abstractions. Of course, The Jazz Composer’s Orchestra grew out of Dixon’s earlier, less documented efforts and is certainly one of the closest counterparts to this music — compare their self-titled album from the following year.

There is a very non-competitive aspect to this music. It asserts itself through a kind of self-actualization, but resists easy comparisons and the sort of jockeying for recognition and prestige that characterizes most other music. That sort of an outlook describes most of Dixon’s career, in which he spent comparatively more time as an educator, recording infrequently and often merely privately.

More than half a century later, this album still sounds unique and impressive. That is to say it hasn’t aged a day. But that shouldn’t surprise, because while this certainly is a part of the social fabric of its time, it was always a work of unique self-expression that showed no deference to commercial trends or fads.