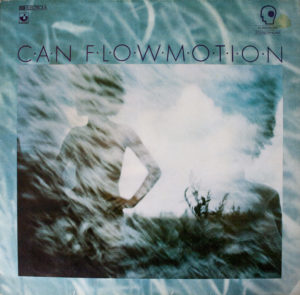

CAN – Flowmotion Harvest 1C 062-31 837 (1976)

Flowmotion is very nearly a great album. Bassist Holger Czukay described it as “innovative and eclectic” and “one of Can’s underrated albums.” He is right on both counts. Fans have been sleeping on this one.

The album has a strange reputation. The opening “I Want More” was a hit single in the UK, and one of the band’s biggest commercial successes of their entire career. Yet, at the same time, fans and critics have often expressed skepticism at that song and the album as a whole.

Undoubtedly, this album sounds markedly different from what the band had previously released. There were influences of reggae and disco. As one reviewer noted, the album has a “casual, Caribbean feel”, characterizing it as “a worthy and sincere engagement with then-current trends (which, come to think of it, is exactly what Can was doing in ’68. It’s just that ’76 was no ’68. Should Can be blamed for changing with the times, or is Western society itself the culprit?)”. The back of the album jacket featured two hexagrams from the I Ching: Hexagram 29, 坎 (kǎn), “gorge” or “the abyss” (in the oceanographic sense), which has inner and outer trigrams that both represent water; and Hexagram 59, 渙 (huàn), “dispersing” or “dissolution”, which has an inner trigram for water and an outer trigram for wind.

The ambivalence to this album — if not outright dislike of it — might be best understood in the context of general trends and the generalized backlash at disco at the time. As has been well-documented, the “disco sucks” movement was largely driven by homophobic and racist sentiments (even if the individualism it represented could be critiqued on rational grounds). Disco-bashing has also become a somewhat of a quasi-elitist stance — disco becoming associated with the working class and the less educated. For that matter, there were many albums going for a “tropical”/”Caribbean” feel around this time, and most were pretty bad. Flowmotion was probably just lumped in with other music that was chasing fads. That was probably the kiss of death for its critical reception, especially for a band characterized (sometimes unfairly) as being sui generis and as making music without precedent.

“I Want More” is a light funk-disco dance number, bizarre in having no lead vocalist, only background vocals. Mostly the singing is a kind of group chant, indistinct and diffuse. Against an infectious and repetitive guitar riff, there are single note keyboard interjections from Irmin Schmidt while drummer Jaki Liebezeit seems to (subtly) play two layers of rhythm at once, one slow and the other in double time.

“Cascade Waltz” is a whimsical number that crosses a reggae beat and slurred, tropical guitar lines with a formal European waltz (and foreshadows the band’s 1978 single “Can-Can”). Michael Karoli‘s deadpan vocals add yet another dimension to the song, one seemingly at odds with both the prim formalism and sunny playfulness floating around.

“Laugh Till You Cry, Live Till You Die (O.R.N.)” is kind of the heart of the album. Karoli is overdubbed on electric violin, guitar and bağlama (a kind of Turkish lute). This song comes the closest to straight-up reggae. The balance between genuine experimentation and accessible pop catchiness is spot on. Jazz records that do this are often described as being “inside” and “outside” at the same time. If Karoli is the star of that song, he powers the closing title as well — a more than ten-minute purely instrumental excursion with ambient washes of keyboard, menacing swells of bass, and swirling psychedelic guitar solos. “Flowmotion” is sort of the late-1970s counterpart to the band’s epic “Mother Sky” (from Soundtracks).

“Bablyonian Pearl” is kind of a goofy novelty song. It seems like a meeting of “Full Moon on the Highway” (from Landed) and “Come Sta, La Luna” (from Soon Over Balauma) over a loopy, slightly reggae-tinged beat. “…And More” was the hit single’s B-side. It is kind of a throwaway here, and is also the shortest song. It isn’t bad, though, and might work as incidental film music.

“Smoke (E.F.S. No. 59)” may have been the band “getting back into the sixties again“. But that sinister, gloomy track is totally at odds with the rest of the album. It represents a sequencing problem — kind of like the “We Will Fall” problem (in reference to the song from The Stooges‘ debut album). The song itself is perfectly fine, except that it totally disrupts the album and doesn’t belong alongside tunes that are within reach of Jimmy Buffett.

What does all this add up to? That is sort of the main question this album presents. There are great songs here. Yet the album as a whole struggles in places, due to sequencing more than anything else. Replacing “Smoke” with something more in line with the rest of the songs would have been an improvement — perhaps like “Sunshine Day and Night” from the generally tepid follow-up Saw Delight. There is also no denying that CAN was still genuinely experimenting, and those experiments pretty much all succeed. That they could experiment while also making overtures to accessible pop music is a real achievement. Usually such efforts have a high “degree of difficulty”. In hindsight, listeners who can get past biases against either pop music or experimental music (as the case may be) might find much to like here.