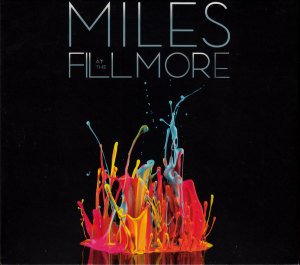

Miles Davis – Miles at the Fillmore: The Bootleg Series Vol. 3 Legacy 88765433812 (2014)

Although Miles Davis released many highly popular albums in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the density of the creative energy of his bands during that period resulted in more recordings than albums. His record label, too, didn’t quite know what to do with it all, though they did lend support — largely responsible for the commercial successes Davis did find.

This archival collection of live recordings comes primarily from June 1970 shows at Bill Graham‘s Fillmore East “rock palace” ballroom in New York City, with three “bonus tracks” recorded at the Fillmore West in San Francisco in April of the same year. Material from the Fillmore East shows had previously been released in edited, medley form as At Fillmore, an album once well liked that certain fans have increasingly criticized for its editing of the source material.

While most music, even to this day, has to pick one style and stick with it, Miles’ fusion bands found ways to present multitudes of styles, sometimes all at once and sometimes in serial progression. At the Fillmore East shows, he had two keyboardists, Keith Jarrett and Chick Corea. We hear the speedy, busy runs of notes from Corea, sounding almost like electric guitar virtuosos in the Hendrix mold. But at the same time we get large block and washes of sound, with bent, clipped and embellished edges from Jarrett almost like Sun Ra‘s afro-futurist experimentations.

This is a sleeker, more contemplative version of Miles’ fusion music, fluid and open, with lots of space and athletic energy. The performers are separately identifiable in a way not unlike Miles’ bands back in the hard bop era. Sure, they bleed over and surpass that paradigm, but it still represents a common reference point for the performers. In the coming years, Miles’ music would grow more menacing and angrier even, certainly heavier and denser. As time went on, the musicians worked more as a kind of monolithic unit, more actively coordinated — in the studio this was merely the impression given and not the reality of the recording process, which was quite the opposite in terms of literally isolating and separately recording individual performances. But the moment in time captured on Miles at the Fillmore is one in which these bandmembers, all, are sort of the vanguard thinkers, sharing ideas, building off each others’ contributions, mapping out the field of the possible.

Bassist Dave Holland plays a key role in the sound of the band. He is more like another soloist than a part of rhythm section. Holland can (and does) play catchy lines on his electric bass, but he doesn’t always provide a syncopated rhythm in sync with drummer Jack DeJohnette (key examples: “Directions,” “Sanctuary”). Holland is sometimes fairly far down in the mix, and his contributions can blend with the horns and the keyboards. In that shadowy place of blurred lines, he shifts the momentum of the music, urging the other players one way or another. Miles often gets credit for doing that. But Holland did it too, often more in the sense of trying to herd cats at a full sprint.

There are now many recordings available of Miles’ period of transformation and growth as a live performer from 1969-1971. Many of these documents are stunning in their own right. Still, Miles at the Fillmore might be the very best of them. The audio fidelity is undoubtedly superior to the others. the band, too, sounds as alive and engaged as anywhere else. Saxophonist Steve Grossman has definitely settled into the group, and makes more substantive, meaningful contributions than on recordings from earlier in the year (Black Beauty). His playing is punchy, noisy and even a little greasy sounding. None of the other saxophonists Miles played with in the 70s had a sound like that. Most played in a more sustained way to blend into the sonic fabric.