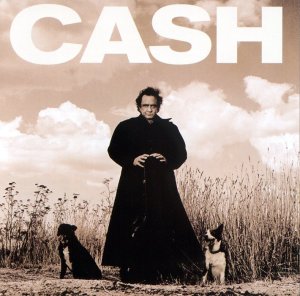

Johnny Cash – American Recordings American 491797 2 (1994)

Johnny Cash made one of the biggest comebacks in memory with American Recordings (perhaps only Louis Armstrong‘s surprise 1964 hit “Hello, Dolly!” comes close). Cash had struggled for the preceding two decades to maintain an interest in recording as well as to find a producer that could do justice to his older voice. It wasn’t that Cash’s many previous albums were all bad, but they were uneven and often misguided. They usually tried to take him and fit him into current trends, however awkwardly (think Leonard Cohen‘s unfortunate meeting with producer Phil Spector on Death of a Ladies’ Man). That was a mistake because it tended to devalue what made Cash so great — that rich baritone voice and his disarming earnestness — by insisting that he could only succeed by transforming himself into something else. Unlikely enough, though, by the late 1980s Cash was quietly changing all that. He made a few albums that, while still rather mediocre, had a stately feel that was quite natural for his new coarser and more gravelly voice, which subtly (or unsubtly – “Beans for Breakfast”) had more vibrato than years before. But he was still dragging along a backing band that should have been put out to pasture long ago. And the production values on so many of his albums had still lurched between various fads, from countrypolitan to urban cowboy, that haven’t aged well.

Rick Rubin, who rose to fame in the world of hip-hop and later extended his reach to rock and metal, sought out Cash and made him the key signing for his newly-formulated record label American Recordings (formerly Def American). What Rubin did wasn’t all that surprising. The popular television specials “MTV Unplugged” had been presenting a variety of rock/pop musicians in low-key acoustic settings with great success. And other established artists like John Cale (Fragments of a Rainy Season) and Bob Dylan (Good as I Been to You) had found renewed success (at least critically) with solo acoustic recordings in recent years. Also, Willie Nelson had recently released the collection of stripped down recordings of old tunes (The IRS Tapes: Who’ll Buy My Memories?) to help pay off well-publicized tax debts. Rubin applied that popular trend to Cash, and it was a perfect fit. All the dross that cluttered Cash’s albums for so long was immediately stripped away. Rather than trying to sound like what was popular at the time, he could just sound timeless. It’s only his voice and an acoustic guitar. Everything comes through on record very clear and natural. Cash gets to be Cash without anything to stand in the way. It helps too that Cash gets to re-record songs he’s done before (like the hauntingly grisly “Delia’s Gone”) with a smattering of other cover songs that seem tailor-made for him. By keying into the darker side of Cash’s music, this album also appealed to rock audiences that maybe had heard the name Johnny Cash but never bothered with his music before. While still ignored by much of the country music establishment — which incidentally had not done much of value for decades — this album succeeded in launching Cash into the booming music market of the 1990s, the last time (as of this writing) there was any effort by mainstream media to push music of any substantive quality. Of course, a big reason that Cash was able to find so much commercial success in this comeback was the marketing effort put forward on his behalf for the first time in a long time. It was all black & white photography, bold lettering of the name CASH, and a confident, lived-in and knowing ambiance, with a hint of rural underclass danger. Rubin does deserve credit for looking to Cash when no one else would, and for matching him up with a recording style and marketing package that suited him. Plenty of songs from these sessions that didn’t make it onto the album ended up on the very good box set Unearthed.