Paul Bley Quintet – Complete Live at The Hillcrest Club Gambit 69272 (2007)

Wow. In short, what you have here is pretty sloppy packaging of some great music.

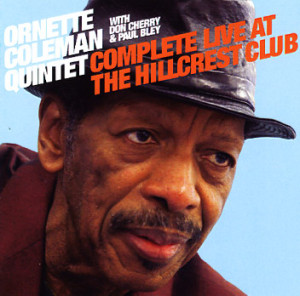

The packaging: Well, to begin with, the cover and liner features a photo of Ornette Coleman that must have been taken close to 50 years after the music was recorded. Then the tracklist is messed up completely. Track number five is labeled “When Will the Blues Leave?” and track seven labeled “Ramblin'”, while track five is clearly “Ramblin'” and track seven is clearly “When Will the Blues Leave?” when you play the music. Then, there is the fact that this is credited as an Ornette Coleman record. Strictly speaking, these recordings were made at gigs led by Paul Bley where Ornette and Don Cherry just sat in. But, Ornette does steal the show, there are tons of Ornette’s compositions here, and Bley was so profoundly influenced by Ornette that maybe it’s only slightly misleading to call the album Ornette’s own.

The music: Awesome. Previously released on Paul Bley/Ornette Coleman/Don Cherry/Charlie Haden/Billy Higgins: The Fabulous Paul Bley Quintet and Coleman Classics, these live recordings show that, musically, Ornette was leaps and bounds ahead of what his problematic first studio album suggested. The landmark contribution Ornette made to jazz was in disengaging improvisation from a verse/chorus format built around repeating harmonic structures, and turning it into something that seems to continuously move forward, as Paul Bley explained in his September 2007 interview in The Wire magazine. It’s a style more linked with serialism in Euro-classical music (think Anton Webern) than the hard bop and cool jazz traditions still in vogue in 1958.

In truth, the sound quality here approaches that of a bootleg. Billy Higgins and especially Charlie Haden sound quite muddy in the mix, and Bley is hardly audible when comping — only becoming distinctly clear when taking solos. Yet the horns come across quite clearly. Don Cherry is in a surprising form, playing with a delicacy on “How Deep Is the Ocean” rarely associated with him. But Ornette is really front and center here, showing why he is known as one of the greatest stylists and soloists. Well, perhaps Ornette’s talents aren’t quite as popularly recognized as they should be. Bley once described the negative reaction to the music at the Hillcrest Club, which catered to a predominantly black, working-class audience. He exaggerates some (audience chatter and even applause is audible on the recordings), stating that when his band with Coleman and Cherry took the bandstand:

“Several things happened almost at once. The audience en masse got up, leaving their drinks on the table and on the bar, and headed for the door. The club literally emptied as soon as the band began playing.

“For the duration of that gig, if you were driving down Washington Boulevard past the Hillcrest Club you could always tell if the band was on the bandstand or not. If the street was full of the audience holding drinks in front of the club, the band was playing. If the audience was in the club, it was intermission.”

Stopping Time: Paul Bley and the Transformation of Jazz (1999), p. 63.

But then, Goethe offers the following in his travelogue Italian Journey, Part One (1816):

“One gets small thanks from people when one tries to improve their moral values, to give them a higher conception of themselves and a sense of the truly noble. But if one flatters the ‘Birds’ with lies, tells them fairy tales, caters to their weaknesses, then one is their man. That is why there is so much bad taste in our age.”

In quite a later age too Johann.