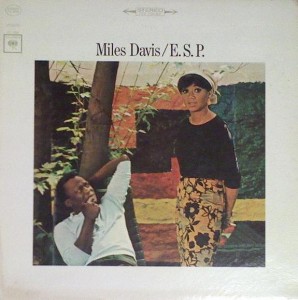

Miles Davis – E.S.P. Columbia CS 9150 (1965)

In 1965, Miles Davis made a slight break from the East Coast hard-bop he pioneered over the past decade. E.S.P. was the first studio album from Miles’ second great quintet: Herbie Hancock (piano), Wayne Shorter (tenor sax), Tony Williams (drums), and Ron Carter (bass). At every turn, the group breaks convention. E.S.P. is not as popular as other Davis albums, but it remains as great as any other recordings by any of Miles’ groups. It’s the intriguing launch point for what Miles did over the coming years.

Miles Davis never had to practice. He had the remarkable ability to immediately remember any music he heard (a phonographic memory?). His band did not feel quite the same way about skipping practice, but they certainly had to deal with it. The rhythm section was left hanging to fashion their own ideas about the music — even more so on their next album Miles Smiles. Miles always said he didn’t know what the fuck the band was doing “back there.” Well what they were doing back there was playing great jazz. Left without structure and guidance, the rhythm section found themselves experimenting with new forms and styles. E.S.P. is a great example of the jazz ideal of making it up as you go. Tony Williams (just nineteen!) showed early indications of fusion with some straight drumming on “Eighty-One” (“straight” means, for example, instead of accenting the 2nd & 4th backbeats in 4/4 time, all the beats are accented the same).

Herbie Hancock started to use “no left hand” as Miles instructed. The space and lighter voicing holds the horn solos. The piano sounds more like another horn. Wayne Shorter gracefully delivers melodic solos, while the trumpet coats the sax in sleek harmony. Miles’ magic mute appears for “Agitation” with attentive snaps in front of Ron Carter’s vamps. Miles then boldly lays down his vibrato-less blasts on “Iris.”

The sound is delicate and always compassionate. Tonality is hardly constant, slowly removing traditional bop structure. The songwriting encompasses contributions from most of the group, though Wayne Shorter would later take over most of the writing.

Miles Davis refused to let music evolve past him. He reaffirms his place as one of the great bandleaders and visionaries by assembling a remarkable band that delivers on every ounce of potential. E.S.P. was elegant 1960s jazz that needed not shy away from the free jazz movement.