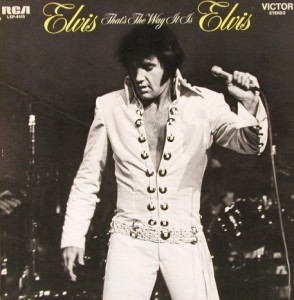

Elvis – That’s the Way It Is RCA Victor LSP-4445 (1970)

Another good one from Elvis’ second golden era. Just look at the album cover! That, my friends, is an Elvis album cover.

When Elvis made his musical comeback with a 1968 TV special, after about a decade wallowing in dreadful Hollywood B-movies, he did something that is the hallmark of every musical comeback. He took a kernel of something that was always present in his music and thrust it to the forefront. Other examples are Leonard Cohen and Johnny Cash. When Cohen came back in the late 1980s, he made a change from his reputation as a purveyor of depressingly dark songs to a kind of jokester delivering deadpan humor left and right, but in hindsight the humor and wit was always there. He was always winning over listeners by creating a sense of mutual belonging, and that frequently meant that he used humorous devices. When Cash came back in the early 1990s, he emphasized his voice almost in isolation and sang mostly songs with dark themes, occasionally with a sardonic approach. He resurrected his voice as his greatest strength. Yet Cash’s voice had always been a major strength. He always used it as a force that could not be contained, by anyone, anywhere. With Elvis, his post-comeback period banked on one characteristic: his charm. There was a documentary film (That’s the Way It Is) made in conjunction with the making of the album, and in both the studio sessions and the live concerts Elvis is utterly charming. In the studio he joked with his band, and effortlessly switched between “bandleader” directing the shape of the song arrangements and “buddy” goofing around with his friends, and in that way building up a rapport with his band that gets him the desired recording. On stage, he was always enrapturing his audience, whether leaning down at the edge of the stage to give out kisses to audience members, or joking about his pants being too tight as he bends down closer to the audience or does karate moves. Of course, he was always a charmer, but when he arrived on the national stage in the 1950s he relied more on a cool, rebellious swagger and brashness than pure, unadulterated, charismatic charm. But even during his ’68 comeback special, he laid on the charm when conducting more intimate sessions with his old supporting musicians, running through some of his old, classic rockabilly songs. The charm built connections to the audience. This provided context for the rest of his music that would not otherwise be there. The audience can listen with different ears.

During this Vegas show period, Elvis developed a band and a sound that fit his charming personality — of course later on this would be a liability as he seemed to struggle to turn it off and lacked meaningful personal relationships as a result. Following somewhat the template of pure pop (showtune) singers like Judy Garland, he did big, orchestrated pop and soul songs that gave him opportunities for soaring vocal treatments. Songs like “I Just Can’t Help Believin’,”You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me,” “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” are nothing short of amazing. It’s the smooth, sultry power of Elvis’ vocals that gives the performances a sense of overwhelming intensity. And there is no need to resort to flashy gimmicks (like Liberace). This music just feels big and commanding, as if it simply has to. Elvis doesn’t have to pull the music along. It as as if he is tapping into something bigger than even him. The weakness of this album is that a few of the studio tracks — “Twenty Days and Twenty Nights” and “Mary in the Morning” — kill the energy maintained by the rest of the album.

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu said (in Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste):

“Charm and charisma in fact designate the power, which certain people have, to impose their own self-image as the objective and collective image of their body and being . . . . The charismatic leader manages to be for the group what he is for himself, instead of being for himself, like those dominated in the symbolic struggle, what he is for others.”

For Elvis, this holds, it seems. His earthy and muscular emotional range embodied a kind of work ethic. It was a style that valued the hard work and labor that goes into his music. An audience that valued a life of work could relate to such an attitude. But Elvis, too, was nimble and varied in his use of these attributes. And he suggested a virile benefit to this sort of an attitude. But none of this is forced on the audience by the music or Elvis’ performance. It is assumed by the totality of the show.

Elvis’ approach was unlike that of other Vegas-style entertainers. Axel Stordahl was the conductor who worked with Frank Sinatra in the 1940s. It is instructive to contrast the approach of Elvis and his orchestral conductor Joe Guercio. Stordahl deployed syrupy and treacly strings that established a rather static foundation upon which Sinatra crooned. It conveys a sense that the singer is in his place. The music will not go anywhere. It will remain where it belongs. And in that space, the singer, and he alone, has the ability to deploy his considerable talents to dazzle. It is actually a fairly simple twist on a rather old performance trick. Sidney Bechet, the jazz saxophonist, used basically the same trick in an earlier era. A “star” soloist working with a large orchestra will have the orchestra “sandbag” their performance. That is, they play simple stuff, that lumbers or is overtly bland, or maybe even feigns a kind of sourness. Any or all of this provides a foil for the star soloist to work against, allowing even small and otherwise unimpressive embellishments to seem bigger and flashier than they really are. It wows audiences by suggesting that the soloist is better than them, because not even the backing musicians can do what the soloist does. This is partly the secret of Sinatra’s music with Stordahl. In Bechet’s case there was a twist. There at least in context there was a statement that said even a black man (legally a second-class citizen) was better than some others, though problematically the use of orchestra sandbagging undermined that claim by presenting it as (only) a lie — Louis Armstrong would have to come along to prove it to the doubters while working in front of great musicians for the point to be indisputable.

Elvis had a sweaty, visceral energy to his performance that made the forward drive and power of the entire ensemble palpable. He worked with a conventional guitar-based rock band, complete with drums and electric bass. This provides syncopation that propels the music forward. The orchestra extends and fills out the sound of the rock band. The Guercio orchestra didn’t sound static at all. They use swelling dynamics to accentuate dramatic surges, and the wind instruments extend beyond conventional limits for proper tone to have a pulsing drive that magnifies the energy level. It’s a kind of modernism that calls attention to the medium of orchestration itself. The distinction may be subtle, but the Guercio orchestra adds more than punctuation to the rock band or padding to the tonality of the rock band’s instrumentation (though they do some of that too). They provide a kind of raw mass to the overall sound, that has the feeling of movement along with the rock band and Elvis’s vocal. An analogy would be to movies, in which the good guy or bad guy, usually one possessing magical or superhuman powers, floats into a scene accompanied by fog or smoke. The fog/smoke billows along with the character, filling up the space on screen, conveying a sense of power larger than the actor’s physical build. This is what Elvis’ great Vegas stage show delivered in its prime. It was the musical equivalent of expanding a sense of space in film. But rather than the kind of laser light shows that became a side-show fad for some rock acts, this was a musical force that envelopes the audience. This is the key difference between Elvis and the other sorts of entertainers that preceded him on big stages.

Elvis’ show was about making and maintaining an emotional connection to the audience. The audience was positioned at his level, not as an aside, but in both his music and in his on stage antics (kissing audience members, etc.). Go back to Judy Garland’s style. On her famous Judy at Carnegie Hall live album she tells a funny story about a hairdresser in Paris. While this story does charm the audience, it simultaneously reaffirms her elitist stance vis-a-vis the audience. Going to Paris (for work or otherwise) is not the stuff of the ordinary person on the street. Elvis sings songs on That’s the Way It Is that are overwhelmingly about personal relationships. This is something that anyone walking in the door to a Presley concert, no matter how humble, has the potential to relate to. When Elvis emerged in the 1950s as the symbol of youthful rebellion, it was partly an earnestly apolitical stance that wagered that social elites would not recognize how his swagger and songs about earthly romance could build a bridge across Jim Crow racial lines by way of an audience of youth. Elvis’ “comeback” likewise used his charm through the medium of romance songs to advance revolutionary democratization through music. What made his comeback so remarkable was how he had managed to reconfigure the sound and instrumentation of his music to use the same element of charm to achieve a different objective. Elvis undoubtedly deserves the title of “king” bestowed upon him, because he did these things with a kind of aristocratic benevolence. These aren’t new ideas. But Elvis actually pushed them forward to a wider swath of the population and therefore more effectively than maybe any other.

Addendum: There is an expanded edition of the album That’s the Way It Is: Special Edition (2000) that is worth it for the fan. The third disc has outtakes that run a bit thin in places, but the collection includes two entire concert performances with stellar performances that build on the success of the original live/studio album.