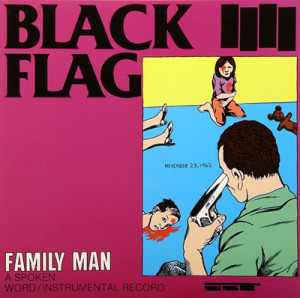

Black Flag – Family Man SST 026 (1984)

You might say that Black Flag represented the very best qualities of a rock band from the country that gave birth to rock and roll. They did new things and they pushed boundaries. They came up in the late punk scene, one in which there was no “entry code”. Anyone could self-identify as a “punk” — just like James Franco‘s character starts calling himself a “punker” in an episode of the TV show Freaks and Geeks (incidentally, Franco is heard listening to Black Flag in that episode). But even without an entry code, there ended up being a lot of conformist behavior in the punk scene. Many punks practically wore uniforms! Black Flag vocalist Henry Rollins commented in the documentary Punk: Attitude that lots of punks ended up being a lot more close-minded than they promised. Rollins can safely say that because Black Flag was most definitely not made up of those kinds of punks. Although in their first four years, Black Flag seemed like a band fairly close to the norm, with just a better guitarist than most — Greg Ginn — and less fashion sense. But as time went on it became clear to anyone paying attention that Black Flag was actually really different. They had long hair to piss off the close-minded punks in the audience. And what is more punk than that!

After a draining legal battle, the band emerged from hiatus in 1984 with what seems like a truckload of albums. The third (or second?) of them was Family Man. It raised the stakes considerably for how far the band was willing to go. Punk bands, before or since, were NOT releasing albums of roughly half spoken word pieces and half instrumentals. Granted, the origins of punk lay in college-educated poets like Patti Smith, with very clear connections to literary and performance art circles. Even Lydia Lunch came to fore in a scene of like-minded artists. But when Rollins started doing “spoken word” (not that the term was even well-associated with it at the time), he did not come from any formal background in literature. He took a very DIY (do-it-yourself), self-taught approach. Side one of Family Man is devoted entirely to Rollins doing spoken pieces. His words are, well, a bit juvenile and fueled by a disturbing amount of aggression and rage. But, he is very earnest about what he is doing. It also takes a considerable amount of guts to try to break spoken word performances to fresh audiences on the West Coast and Midwest with little or no reference points. Punks would have found more refined performance at a William S. Burroughs reading, but that’s not really the point. The real point is that Rollins was doing what he thought mattered even when it wasn’t what was expected — or accepted. His earliest attempt here might be a bit rough-hewn, but he did get better going forward.

Side two of the album opens with “Armageddon Man,” the one true full-band track. Even though that might lend the impression that it’s the “classic” Black Flag sound, it’s hardly that. It’s another extended jam, running over nine minutes. From there, the rest are instrumentals. Guitarist Greg Ginn has plenty of space to stretch out and he makes the most of the opportunity. It’s worth noting that side two is probably bassist Kira Roessler‘s finest moment with the band on record. Drummer Bill Stevenson sometimes struggled to mesh with Ginn, but he does okay here, in spite of a few patches where it takes him a moment to lock into a good groove. The influences on side two run the gamut. The jammy, long-song format takes a cue from Ginn’s adored Grateful Dead. But telling is the closer “The Pups Are Doggin’ It,” with Kira playing a bass line cribbed from “Right Off” on Miles Davis‘s A Tribute to Jack Johnson. The jazz influences in Ginn’s playing work best when Stevenson hits a hard beat along the lines of what the great jazz drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson would do. The results on the second side of the record are much more replayable than the first side. For that matter, the instrumentals simply rock harder and come together better than on the following year’s all instrumental EP The Process of Weeding Out.

The best thing about this album is its capacity to surprise by taking chances and breaking the mold for what a hardcore punk band was supposed to be like. The relentless drive to try to evolve and rethink the very foundations of the band’s sound take this album beyond just the literal contents of the recording. An album like this provokes a dialog. The outcome of that dialog can be anything…and the ending isn’t written yet.