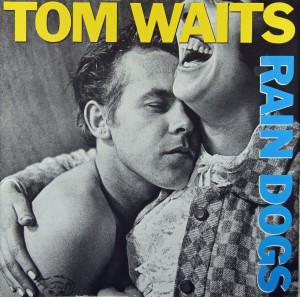

Tom Waits – Rain Dogs Island ILPS 9803 (1985)

Easily Tom Waits’ greatest achievement. It’s a ramshackle wreck of a thing, and no two songs are great for quite the same reasons. This one will stay with you for a lifetime.

Waits met his wife Kathleen Brennan while working on the film One From the Heart (1982). He relocated to New York City from Los Angeles. This album succeeds in part by jettisoning the last vestiges of his LA sound and fully embracing the freaks, the losers, the rabble — what Barney Hoskyns called a focus on “the urban dispossessed,” inspired by Waits’ recent contribution of music to the documentary Streetwise (1984) about homeless kids in Seattle.

Brennan introduced Waits to the work of composer Harry Partch, known for inventing his own instruments and referencing the lifestyle and language of hobos. Wait uses all kinds of junkyard percussion and sounds made without musical instruments as such, with a percussion-heavy emphasis on idiosyncratic rhythms. Partch looms large, and is frequently mentioned as an influence. This is apparent straight from the opener “Singapore” and then doubly so on the next track “Clap Hands.”

Another influence, or at least close comparison, is Lotte Lenya singt Kurt Weill (1955). A gem of a post-WWII look back at the Weimar-era theater songs of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. These were songs from a time of vibrancy, desperation, and possibility, of contradiction and grand change. The songs reflect those circumstances. And Leyna’s 1955 recordings capture the shambolic yet determined and cutting theatrical sensibility that made this music so iconic and emblematic of those times. Here, on songs like “Tango Till They’re Sore” and “Anywhere I Lay My Head,” the piano and horns tap some of the same slightly seedy and bawdy cabaret energy. Marc Ribot‘s flamboyant guitar continues that effect across much of the rest of the album. Waits, who also developed an acting career, always had a flair for theatricality. Rain Dogs turns those impulses toward something shorn of campiness, more gritty, knowing, and subversive.

But this was also the mid-1980s, the era of big pop tunes. And this album has those too. Kathleen Brennan features large here, co-writing “Hang Down You Head” (released as a single) and exerting influence in that direction. There are quite a number of melodic pop tunes here, including the ballad “Time” and “Downtown Train,” the latter being covered extensively. These more pure conventional pop expressions manage to sit comfortably among the more experimental offerings.

And there is more. “Blind Love,” with guitar from both Keith Richards and Robert Quine, is an achingly sad/sweet country-twinged song replete with a fiddle. And there are plenty of tunes like “Big Black Mariah” and “Union Square” that lean on bluesy rock with Waits’ voice barreling forward at its gruffest, not far from Captain Beefheart. These elements of American weave throughout the album.

Not yet has been said yet about Waits’ own performances. His voice is gravelly here. Yet it still draws, subtly, from his early career trying to make a name for himself as a California soft rock singer trading on sentimental emoting, and his ability to cover a wide range of material and deftly push a song into new areas owes to his time singing barroom jazz, and his ability to deliver, with clever and precise phrasing, a memorable mood or sentiment, like on “Walking Spanish” or “9th & Hennepin,” is a more subdued and, at times, unique and personal form of the kind of beatnik monologues he traded in more crudely in the 70s. So, yes, Waits’ vocals help make this album what it is. But, to his credit, this album comes off as a collective effort built on more than just his own presence. Of course, what that makes that possible is the songwriting.

One thing that still impresses about this album decades later is how consistently good the songs are. There are some great songs here. They are full of menace and beauty, characters drifting on the fringes of society, like from a Genet novel, and the eclectic bohemianism of hanging out with the legendary denizens of the storied Chelsea Hotel of the day. And yet these songs are understated, without ever feeling forced or contorted. Perhaps just as important as there being great songs, there is not a bum track to be found.

This remains an essential statement from the 80s, one of those classics that is woven through with signs of the times yet also pointing back to deeper history and standing firmly in its own category.