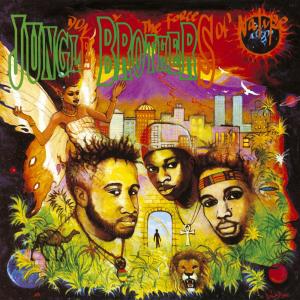

Jungle Brothers – Done By the Forces of Nature Warner Bros. 9 26072-1 (1989)

By the late 1980s, hip-hop was evolving. It wasn’t just about sneakers, nursery rhymes, eating boogers and dancing anymore. But while plenty of artists of the newer generation went for documenting the grimmest aspects of life on the streets or being part of the underclass, a group of artists calling themselves the Native Tongues tried something different. The Native Tongues groups focused more on the positive aspects of what they would want things to be like. Part of that was about respect for the historical contributions of Africans to world civilization.

Unlike most multi-MC groups, the Jungle Brothers didn’t have one MC who overshadowed the others. Everybody shares duties on the mic, and there is never a letdown when another MC takes over from the last. In fact, that is one of the group’s real charms. Part of the reason Done By the Forces of Nature works is that the MCs tend to all use the same vocal rhythm, rather than their own idiosyncratic ones. It is a very staccato, percussive delivery, free of any of the more melodic kind of rapping that emerged a decade or so later. This rhythmic emphasis is a shared approach. So when one MC passes the mic to the next, there is a kind of stylistic commonality that tells the audience that these guys are trying to get at some big, heavy stuff, not trying to cut each other, or anybody else. This is a style that perfectly fits the thematic sentiments of the songs.

The lyrics hint at a new view of masculinity, at least within hip-hop. There is caution and skepticism. This isn’t all bravura (though there is plenty of that). In way, their sexist posturing kind of gives way to brief admissions that all that is just desperate attempts at something they can’t really grasp, leaving open the possibility to maybe taking a new and different look at the world. It would be too much to call these guys feminists, but the ways their songs veer off course from the usual testaments to alpha male status open the door to other things. Most often those other things are testaments to afro-consciousness. But the crazy thing is that if the album had nothing but testaments to afro-consciousness, the people who probably need to hear those the most might not listen, and even those that do maybe would have only focused on everything else.

A clear influence on the Jungle Brothers was James Brown. A really funky beat is absolutely constant. It is a big part of what makes Done By the Forces of Nature so damn infectious from start to finish. Their debut record used a “house music” producer from Chicago, and that gave it a tight, tense, nimble sound. That goes out the window here. A little bit of that is retained, perhaps, keeping this music dance friendly. But the beats meld with the lyrics a lot more here. Take the opener, “Beyond This World,” there is a lot more wordless shouts of “yeah” or “uh” for rhythmic effect. These guys seem much more comfortable, less beholden to the structure of the beats. They make this music their own. These seem like raps over music these guys had lived with. That suits their artistic outlook, giving the album a friendly, down-home brightness that rewards the optimism of the lyrics. It helps that this album was recorded in the “golden age” of hip-hop, before the crackdown on sampling that began in 1991 with a lawsuit against Biz Markie that made choice samples unaffordable to many acts.

Hip-hop was still a semi-unproven commercial prospect back in the late 1980s. It was a kind of specialty genre, with its adherents who probably were insiders to hip-hop culture. Done By the Forces of Nature comes at a key transition, when the forms of early hip-hop were fully refined, but when the scope and direction for the next generation was only being sketched out. The positive, open-minded approach that The Jungle Brothers and other Native Tongues acts put forward didn’t quite catch on like the ghetto tourism aspects of “gangsta” rap. Still, this album hasn’t aged much in two and a half decades. It still has good beats, true to the funkiness of James Brown, though the beats are part and parcel of the overarching sense that these guys were making the kind of music that they like. By extension, they suggest that maybe they could also do what they like when it came to the subjects they rapped about. This is the really subversive edge. The journalistic chronicles of gangsta rap held everything in stasis. They told things as they were. The Jungle Brothers suggested what things might become. Their visions might be a little inept an inarticulate in places. Stumbling in an interesting direction proved a bigger achievement than just being the black news (journalism) network. This was black philosophy: asking better questions.