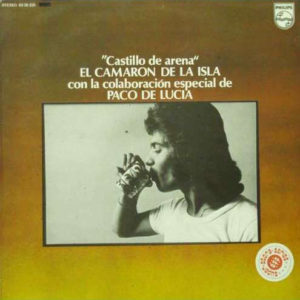

Camarón de la Isla – El Camarón de la Isla con la colaboración especial de Paco de Lucía [AKA Al verte las flres lloran] Philips 5865 026 (1969)

This, the first of many collaborations between El Camarón de la Isla and Paco de Lucía, documents an already fruitful partnership. de Lucía’s guitar is showy. It begs for attention always. Camarón sings in a way that cannot but help commanding attention. Together, those somewhat disparate approaches go together sublimely.

The duo’s take on flamenco music was as groundbreaking a thing as possible under the Franco dictatorship. The Wire magazine, in a feature entitled “100 Records That Set The World On Fire (While No One Was Listening)” (issue 175), said,

““

Flamenco had long been a vital genre. For instance, Niño Ricardo & La Niña de los Peines‘ “Alegrias” is a classic from just before the Great Depression — mentioned in Michael Denning‘s Noise Uprising for its radical connotations (though “alegrías” is a palos or cantes [style], not really a distinctive song title as such). The genre’s golden age ran up to about 1910-20, at which point the “opera flamenca” period began — brought on by preferential tax laws that gave “opera” performances in theaters a lower tax rate than other types of shows. This theatrical style is disliked by some and considered very commercial. Intellectuals tried to return the genre to its golden age roots from the early 20s, but the fascist Franco dictatorship changed all that.

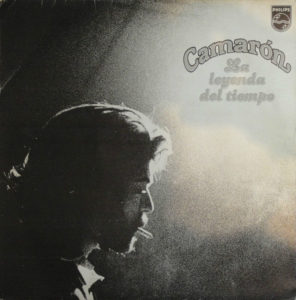

Across the album there is a push-and-pull quality, as emphasis shifts subtle between de la Isla’s singing and de Lucía’s guitar playing. Camarón regularly calls out, “Paco!” This gets a bit tiresome, but it underscores the loose, “jam session” quality of the music — something entirely within the flamenco tradition. The duo’s later work, like their fourth self-titled collaboration and Castillo de arena, is even better, in that it integrated the two performer’s abilities into something more unified and greater than the mere sum of its parts. Still, this first meeting is great on its own terms, and, relatively speaking, perhaps one of the most “traditional”-sounding recordings they made together.