Bob Dylan – Nashville Skyline Columbia KCS 9825 (1969)

It is almost a cliché for pop musicians of a certain vintage not normally associated with country music to release a “country” album. The timing is always when their sales are declining and they are on the long downward slope that almost inevitably afflicts their careers as they leave behind their best years as artists. One sobering truth about the pop music business is that the vast majority of acts have only about five to ten years or so of genuine relevance — if they are lucky to have any relevance at all. Sure, there are exceptions, but taking a large enough step backwards the trend is unmistakable. Yet the allure of doing a “country” album is great enough that it is one of those thing that seems inevitable for long-running acts. The first major artist to really do it was Ray Charles with Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music. The Byrds did it with Sweetheart of the Rodeo too. Even decades later, Elvis Costello did it with Almost Blue, Frank Black did it with Honeycomb, etc. Nashville Skyline was Dylan’s foray into full-fledged country music — he had recorded in Nashville before, but he wasn’t pursuing country music then. The reasons Dylan or anyone else would make a record like this are many-fold. There is usually some crass motive to find cross-over success (reach new demographics and potential new sales!). Sometimes it’s just a self-indulgence that past success has enabled (always loved country music but didn’t have the credentials or label support to make it happen before, here is a chance for a vanity project!). Or it could even be slumming (oooh, making a country album would be something different and exotic!). Other times, it’s just desperation (writer’s block and creative dead-ends…hmm, well, why not a country album?). It’s become something a little more shocking for a non-country artist to make country music in the Unites States, given the social context of modern times. Popular country music, from the countrypolitan era onward, has really severed many ties from its origins in folk music. It’s often a campy self-parody that talks down to its listeners. Add to that the fact that urban middle-class liberals tend to harbor great hostility toward “rednecks” (the rural poor) and even blue-collar types (the urban working class) and it is the “rednecks” and some of the urban working class that are the core audience of modern country music.

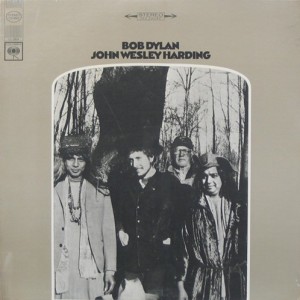

So where do Bob Dylan and his Nashville Skyline fit into all this? For many, this was the album that marked the beginning of the end for Dylan. His early years showed him to be a talented but not iconoclastic folk singer. He stayed within the bounds of that tradition. But then he went electric, shocking and appalling many narrow-minded folkies, and in doing so his songwriting adopted the currency of the beat generation. It was this mid-Sixties period that made Bob Dylan into a cultural icon. But by the end of the decade, and after his motorcycle crash, he was largely done with his beat-poet songwriting. John Wesley Harding presented a slightly different type of songwriting, built more around mythology and simpler, less literary forms. But traces of his earlier styles remained. This, his next album, would be a kind of break, looking into completely new areas for a new style of songwriting.* Dylan looked to country music.

This is an effective album, even if it’s not littered with classic songs. The re-make of “Girl From the North Country” sung with Johnny Cash and “Lay Lady Lay” are the standouts (in spite of Dylan and Cash singing different lyrics at one point in their duet). But the rest is still quite good. This is no Highway 61 Revisited or Blonde on Blonde, but what is? Dylan certainly had no hostility to the working class, and even proved to have a very conservative affinity to it that confused many who labelled him a countercultural revolutionary. The key to this album is that Dylan wasn’t just slumming. He had a genuine appreciation for country music. It may not be his forte exactly, but he manages to demonstrate some versatility. The bad news in all this is that this was just the first instance of Dylan flapping in the wind for the next many years trying out new things — without really sticking with any — and generally just losing touch with his strengths as a songwriter. But what happened later should not tarnish this album, which is quite good despite falling short of being a major classic. And while this feels a tad escapist, like Dylan trying to cheer himself up with a dose of music he had long appreciated from a distance, well, he makes a convincing go of it.

*My hypothesis is that celebrity-status Dylan didn’t read as much poetry anymore and lost touch with that element.