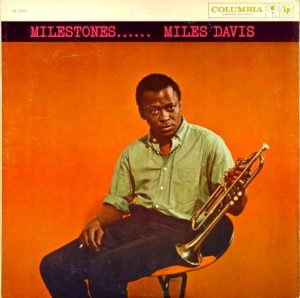

Miles Davis – Milestones…… Columbia CL 1193 (1958)

This is an album I never quite understood, at least until recently. Future Davis sideman Tony Williams loved it; I think he said it was a favorite. Others love it too. But why? For the most part, it’s fairly straightforward hard bop. I guess, in retrospect, the late 1950s weren’t exactly a fertile time for jazz music (other than for the likes of Sun Ra, Cecil Taylor and Ornette Coleman, that is, none of whom achieved any meaningful commercial success). It was generally a low point. Sure, there were some good albums that appeared at that time, but most players were still milking either hard bop or cool styles for all they were worth. The free players who hit big in the sixties either hadn’t fully developed their styles yet, or, more importantly, hadn’t found many recording or performance opportunities yet. Coltrane is here. Yet Coltrane was a good but unremarkable player in Davis’ first great quintet. He is starting to show signs of what he achieved on early albums like Giant Steps, but it was a few years after Milestones that Coltrane really became Coltrane.

What occurred to me recently was that this album represents and complacency and bourgeois aspirations of Miles and his associates. While the rollicking “Two Bass Hit” features a fun and playful riff, most of the material here relies on up-tempo rhythms to mask simplistic and thin ideas. Above all this music presents itself as the pinnacle of something — rather than, as history would later prove it to be, an anachronistic holdover from the be-bop era, sustained only by the suppression of the likes of Ornette Coleman. Put another way, this music presents a linear view of history as a straight march of progress in a particular direction, and obscures how it really is music that participates in a system of institutional/tribal power hierarchies. When Miles landed at Columbia Records, he was merely promoted within a fixed universe of possibilities. To put this criticism in a more substantive context, this is music still clinging to the model of Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker, in which a black man like Miles was trying to prove himself to be talented, within an established institutional framework (similar to the “Talented Tenth” theory), whereas in the future, after the legal end of the Jim Crow era in America, there would be a great recognition that individual accomplishment within the existing system wasn’t enough — the whole system needed to be changed. Of course, eventually Miles got bored with this, and his boredom led to much better things that did challenge the whole system.