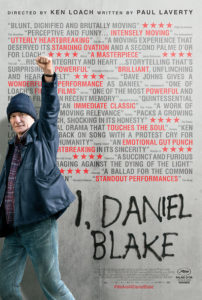

I, Daniel Blake (2016)

Canal+

Director: Ken Loach

Main Cast: Dave Johns, Hayley Squires

One of the best “straight narrative” films I’ve seen in a while — reminiscent in some ways of Mathieu Kassovitz‘s La Haine [Hate] (1995). Basically, the premise of the film comes from Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward‘s theory about social welfare programs being about politically “regulating the poor” rather than solving the problems that create poverty. (It is a modern twist on something that people have written about for a long time). In that respect, the film is meant to convey how the politicians who intentionally — though never explicitly, that is, they never openly admit as much — seek to implement policies that are ultimately cruel to the poor and trap them in extreme poverty have “blood on their hands”. At the extreme end of that spectrum, historically, would be the imperialist British policies in India during the late Victorian era, in which British support for native Indians was at levels less than what the Nazis gave to concentration camp prisoners during WWII (!). While the film’s narrative is pared back from all the complexities of the real world, notably racial animosities used to prevent the kinds of solidarity repeatedly shown in the film, there is nothing far-fetched in the story. The concision is understandable for a film meant to be accessible.

The most blunt premise of the film is unabashedly political: “Does the masses’ struggle for emancipation pose a threat to civilization as such, since civilization can thrive only in a hierarchical social order? Or is it that the ruling class is a parasite threatening to drag society into self-destruction, so that the only alternative to socialism is barbarism?” Slavoj Žižek, Afterword to Revolution at the Gates: Selected Writings of Lenin From 1917 (p. 210). This film argues the latter. And the way it does so is to magnificently depict the so-called “banality of evil”, the way the Kafkaesque bureaucracy mostly turns a blind eye to the callousness of its action in exchange for a (semi) privileged position above those who bear the burdens. It also bears mentioning that I, Daniel Blake makes very modest demands. For instance, the film goes to great lengths to depict the protagonist as someone who has skills (he is a carpenter) who simply can’t work because of a health condition (he recently had a major heart attack), as opposed to defending, say, someone who has no skills but still deserves to be treated with dignity. In other words, the film goes out of its way to make clear it is not endorsing the notion of “to each according to her needs, from each according to her abilities.” It might well have.

A few words for non-British viewers are in order. The plot involves the protagonist seeking social welfare benefits after his doctor says his recent heart attack means that he cannot safely work. In England, there is a national health service (i.e., socialized medicine), meaning that the (unseen) doctor who gives that diagnosis is a government doctor. The welfare officials who deny him benefits constitute a vying faction of the government. What isn’t made explicit in the film is that the Tory (conservative) government of David Cameron had gone to great lengths around the time of the film to purposefully undermine social welfare benefits, for ideological reasons. Those sorts of cruel efforts continued in various arenas under the Theresa May government.