Link to an article by Ty Moore & Patrick Ayers:

Month: October 2016

Critterjams – Scott Adams and Donald Trump

Link to an article on Critterjams:

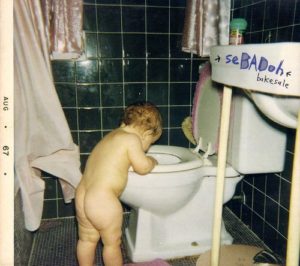

Sebadoh – Bakesale

Sebadoh – Bakesale Sub Pop sp260b (1994)

Here’s a real classic of the grunge/alternative rock period. There is a clear affinity for rough, almost garage rock-ish fuzz, but overall there is much purpose and effort put into establishing a clear and consistent perspective in the recordings. The songwriting retains the emotionally bare confessional tone of much of Sebadoh’s work, while also having rhythmic drive, strong riffs, and a stylistic connection to current genre trends. Balancing — and indeed synthesizing — those sorts of seemingly contradictory impulses is what carries the album. Refreshingly, though, Bakesale avoids the self-pitying mopeyness (and vague graininess) that was the bane of much lo-fi music. Joey Ramone once gave an interview in which he said quite directly that rock ‘n roll was music for outsiders. Bakesale honors that tradition while at the same time serves to rally the freaks (gabba gabba!). Looking back, this album really highlights the best of what the entire grunge/alternative/indie rock scene had to offer.

Michael Hudson – Review of Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice

Link to a review by Michael Hudson of James K Galbraith‘s book Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe (2016):

“Review of James Galbraith, Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice (2016)”

Select quote:

“At first glance the repeated ‘failure’ of austerity prescriptions to ‘help economies recover’ seems to be insanity – defined as doing the same thing again and again, hoping that the result may be different. But what if the financial planners are not insane? What if they simply seek professional success by rationalizing politics favored by the vested interests that employ them, headed by the IMF, central bankers and the policy think tanks and business schools they sponsor? The effects of pro-creditor policies have become so constant over so many decades that it now must be seen as deliberate, not a mistake that can be fixed by pointing out a more realistic body of economics (which already was available in the 1920s).”

This is reminiscent of a quote frequently attributed to Donald Berwick (among others): “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” In the economic context, this notion is also explored further in Economists and the Powerful (2012).

Robert Kuttner – Hidden Injuries of Class, Race, and Culture

Link to an omnibus book review by Robert Kuttner:

“Hidden Injuries of Class, Race, and Culture”

Bonus links: “What Drives Trump Supporters?: Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild on Anger & Mourning of the Right” and “I Spent 5 Years With Some of Trump’s Biggest Fans. Here’s What They Won’t Tell You.” and “Rural Voting from Group Identity Resentment of Other Groups Not Ideology” and “Janesville: Microcosm of the Heartland Rustbelt” (but see “On the Differences of Comedy in the Time of Alt Right Transgression” — essentially rejecting the core premise of Hochschild’s affective sociology as an infantalization)

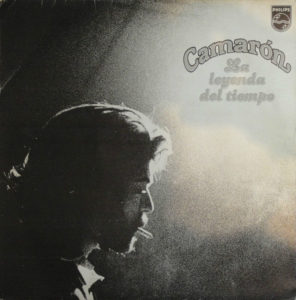

Camarón – La leyenda del tiempo

Camarón – La leyenda del tiempo Philips 63 28 255 (1979)

Camarón de la Isla is credited with being one of the key figures in revitalizing and spreading flamenco music in the latter part of the 20th Century. His voice is more or less perfectly suited to his music: raspy, agile, defiant, emotionally-laden. La leyenda del tiempo (translation: “The Legend of Time”) is considered one of the key documents of so-called “nuevo flamenco.” Traditional flamenco is a folk music that uses guitar (acoustic), vocals, and simple percussion from handclaps and snapping fingers, and is a dance music. It originated in the Andalucía region of southern Spain. The “nuevo” version incorporated many other sounds and instruments: electric guitar, bass, drum kits. In other words, it modernized the music by incorporating aspects of other musical styles, most notably rock. The most modernized tracks here are easy to spot, with synthesizer, electric bass, drums and such — even sitar on the closing “Nana del caballo grande.” And yet, they blend effortlessly with the traditional style of flamenco. The guitar playing (mostly by Tomatito) is just as fiery and detailed, the vocals just as impassioned. It simply has nothing to fear about embracing the modernity all around it. Recorded just a few years after the death of Generalissimo Franco, during the period of a return to a monarchy and some democratizing reforms in Spain, the timing of this music bridging the old and new is no coincidence — the lyrics of fully half the songs are drawn from Federico García Lorca, a member of the “Generation of ’27” who experimented to new poetic forms and was also a martyr of the anti-Franco Spanish socialists whose works had been banned in Spain for a time (until 1953). And yet, the album was a flop upon release, and it actually was reported to have angered longtime, traditionalist fans. As James Kirkup put it in an obituary:

“Flamenco purists deplored his adventurous crossover fusion of flamenco and rock, but they were reluctantly compelled to admit that he was a musical genius who revived the interest of the younger generation in a musical tradition that had been discredited as a symbol of the late dictatorship’s rabid nationalism.”

In spite of controversies he stirred, and the initial lack of success of this album, Camarón remained one of the most famous Spanish performers of his era, and this album has since come to be highly regarded. A comparison to this approach to music on a conceptual level might be Lucio Battisti‘s Anima latina, which has nothing to do with flamenco, but nonetheless, like nuevo flamenco, takes a kind of insular, provincial European music and incorporates international influences (although El Camarón sticks closer to tradition and virtuoso acoustic performance, and features a proud and resilient attitude in place of Battisti’s highly structural existential pondering).

Leonard Cohen – New Skin for the Old Ceremony

Leonard Cohen – New Skin for the Old Ceremony Columbia AL 33167 (1974)

Cohen summons an impressive assortment of styles. It is as if he tries them on, proving how versatile his songwriting can be by demonstrating that all the ones that fit. So take “Lover Lover Lover,” which even concludes with a bit of klezmer clarinet. Of course, then there is “Chelsea Hotel #2.” This is a song you can listen to, start over again, and again, and suddenly an hour has gone by listening to just that one song. It has Cohen’s inimitable sense of intimacy. Cohen later admitted the song is about Janis Joplin. Like a lot of Cohen’s best album-length statements, this one is great not because of one or two key songs, or even the production or eclectic styles. No, what makes the whole album great is Cohen’s brilliant sense of place and social context. He’s for the underdogs, doing what he can for their cause, a kind of consciousness-raising through song, without losing sight of the tenuous position of underdogs and the tactical challenges they face. This is epitomized by “There Is a War.” All said, this is one of Cohen’s better albums.

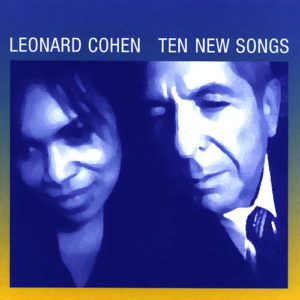

Leonard Cohen – Ten New Songs

Leonard Cohen – Ten New Songs Columbia CK 85953 (2001)

“I fought against the bottle / but I had to do it drunk”

— “That Don’t Make It Junk”

Leonard Cohen, the beautiful loser, has endured as one of the most important lyricists in rock ‘n’ roll history. He has long been a patron of tortured souls. Yet, Cohen is adrift himself. He doesn’t speak from a sturdy pulpit but rather from intermittent places of shelter. Ten New Songs from 2001 was Cohen’s first studio recording since 1992. Acceptance overrides bravura in this glimpse of Leonard Cohen; but as always, his songs present an intelligent view of a complex existence.

The past decades have seen Cohen embark on a spiritual journey that prior to this album included about six years at a Zen retreat (where he took the name Jikan, “the Silent One”). It seems his journey provided at least some resolution. Ten New Songs returns to exploration of the tension of relationships where Cohen still seeks a love he knows he will never find. He has no answers to dispense, but speaks for lack of a better alternative. His voice barely hanging on (it is almost gratuitous to call him a “singer”), he now doles out oddly reassuring commentary from the shadows. In somber tones, Ten New Songs pulls together all the facets of his genius.

The first and last tracks are bright moments and instantly Cohen classics. On “In My Secret Life,” he grapples with a realization that his only actions lie in dreams. Cohen’s quest for truth yields to a hope for any understanding (as on “That Don’t Make It Junk”). His misery collects inside. He tries to make sense of the infinite textures of love and peace. Cohen’s spirituality is still alive in the simple prayers of “The Land of Plenty.” His words do provide, even if only for a moment, unthinkable possibility.

Sharon Robinson, who first worked with Cohen on his 1979 tour, performs the accompaniments almost entirely herself and co-wrote all the songs. She makes an opportune ally in these battles with pain and longing by tempering the fine line between Cohen’s soul and his gravelly monotone. The album cover illustrates, with both heads cocked to their right, the alignment of their thinking. “Alexandra Leaving” find the two in their finest form, singing a classic Cohen tale of fleeting love. Hopefully, Cohen could get by without a collaborator, which may show his continuing desire to utilize Robinson’s many contributions. Perhaps an older — and even wiser — Cohen seeks a compromise.

Leonard Cohen, with Sharon Robinson, has modestly made another album of solemnly dark beauty. His wretched existence continues to expand a legacy of brilliant works. Ten New Songs is a great collection of songs by any standard.

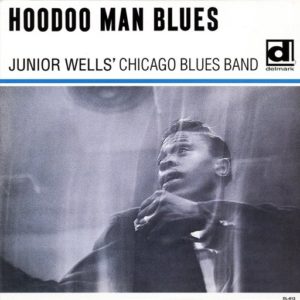

Junior Wells – Hoodoo Man Blues

Junior Wells’ Chicago Blues Band – Hoodoo Man Blues Delmark DL-612 (1965)

In conversations about the best electric Chicago blues albums, Junior Wells’ Hoodoo Man Blues is bound to come up. Sometimes only Magic Sam‘s West Side Soul also contends for that title. The relatively small number of contenders is partly because blues music as a genre was never particularly successful in the full-length album format. During the genre’s numerous peaks, singles were more common. While maybe a couple of songs here are just so-so (“Hound Dog”), most of this is absolutely spot on. This manages to maintain a consistent mood throughout while still changing up the tempo and attack just enough to keep it interesting — like the way the snappy opener “Snatch It Back and Hold It” gives way to the slow, smoldering follow-up “Ships on the Ocean.” Buddy Guy is on guitar, and he gives this a sleek, urban sound that recognizes the role that rock music was playing in supplanting the old prewar style of acoustic blues, particularly in the way he occasionally plays choppy riffs. Wells is in great voice. He is a harmonica player, but his sing-speak vocals come first. The recordings are produced in a smooth and warm way that give this a snap and crispness, while still keeping a chugging bottom end with the bass and drums prominent. It gives so many of the songs a kind of almost minimalist space that is a key to keeping the mood going. That mood is one of sly sophistication. Kind of like the way hip-hop music in the mid/late 1990s developed an emphasis on the “east coast mastermind” persona, Wells goes for some kind of forerunner one (timed just after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the legal end of the Jim Crow era) that emphasizes more of a lothario role, or something that approaches a cunning, “schemer” persona. Whatever it is precisely, he brings across a kind of intimate, feisty independence that is the epitome of charismatic “coolness.” This is one of the best electric blues albums around.

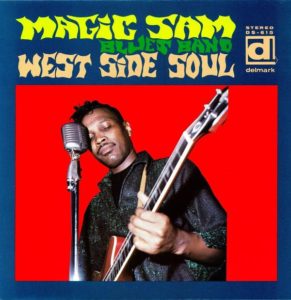

Magic Sam Blues Band – West Side Soul

Magic Sam Blues Band – West Side Soul Delmark DS-615 (1968)

Right off with “That’s All I Need,” Magic Sam establishes that the listener is in for something very special. His soulful voice trembles with vibrato and charms you into his world. The first track is a transcendent blues moment. Not even the rest of the album duplicates those opening lines. Coming in behind the metallic reverb of the guitar, his hope and longing are never fully resolved in song. Magic Sam may have the blues, but he pushes everything back if just for a few minutes.

A legend of electric blues, Magic Sam died tragically young. Before he checked out, he left a legacy that has not been forgotten. He injected a raw and punchy version of the dynamic singing style of a soul (or gospel) singer plus garage-y guitar playing with a faint hint of psychedelia into the electric blues lexicon, while preserving a rhythmic style style reminiscent of acoustic blues of the 1930s and 40s that frequently turns to boogie-woogie. It strikes the perfect balance between delta roots and smooth Chicago styles, with an openness to new developments from genres outside just the blues. The sound jumps from laid-back strumming to cutting solos. Vocals push and prod the band. Guitars pull the beat along at a brisk pace, always responsive to the guiding of Sam’s vocals.

In a unique way, West Side Soul is upbeat and redemptive — electrifying. While covering all the customary blues elements, Magic Sam goes further to lift listeners off the ground. There is always the hanging question of how his stories end, but Magic Sam likes to say there probably is a happy one.

Magic Sam begs listeners to struggle alongside him through his tragic world. The themes are easy to relate to. Heartbreak is not a foreign concept. “I Found A New Love” and “All of Your Love” are not pillars of confidence. Despite his shaky emotions, Magic Sam sets out for something better. West Side Soul is a rare glimpse into a personal transformation. Hesitation weighs against possibility in an eternal conflict.

Songs overflow with energy. “I Don’t Want No Woman” is a frustrated rocker. Magic Sam pleads as much with himself as his woman. The assertion of semi-independence is more a desire to explore for while longer. On Robert Johnson’s “Sweet Home Chicago” the band stretches out in a sly groove. The song now reflects a permanent home rather than a mythical paradise. Mighty Joe Young strides confidently on guitar. Odie Payne is a fury on drums. Stockholm Slim on piano and Earnest Johnson on bass round out this killer band (with Mack Thompson and Odie Payne III featured on three tracks).

West Side Soul is a highly revered blues album. It is also a perfect introduction to electric blues for anyone interested in discovering postwar blues. Not bad for a debut at all.