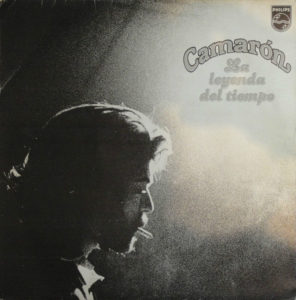

Camarón – La leyenda del tiempo Philips 63 28 255 (1979)

Camarón de la Isla is credited with being one of the key figures in revitalizing and spreading flamenco music in the latter part of the 20th Century. His voice is more or less perfectly suited to his music: raspy, agile, defiant, emotionally-laden. La leyenda del tiempo (translation: “The Legend of Time”) is considered one of the key documents of so-called “nuevo flamenco.” Traditional flamenco is a folk music that uses guitar (acoustic), vocals, and simple percussion from handclaps and snapping fingers, and is a dance music. It originated in the Andalucía region of southern Spain. The “nuevo” version incorporated many other sounds and instruments: electric guitar, bass, drum kits. In other words, it modernized the music by incorporating aspects of other musical styles, most notably rock. The most modernized tracks here are easy to spot, with synthesizer, electric bass, drums and such — even sitar on the closing “Nana del caballo grande.” And yet, they blend effortlessly with the traditional style of flamenco. The guitar playing (mostly by Tomatito) is just as fiery and detailed, the vocals just as impassioned. It simply has nothing to fear about embracing the modernity all around it. Recorded just a few years after the death of Generalissimo Franco, during the period of a return to a monarchy and some democratizing reforms in Spain, the timing of this music bridging the old and new is no coincidence — the lyrics of fully half the songs are drawn from Federico García Lorca, a member of the “Generation of ’27” who experimented to new poetic forms and was also a martyr of the anti-Franco Spanish socialists whose works had been banned in Spain for a time (until 1953). And yet, the album was a flop upon release, and it actually was reported to have angered longtime, traditionalist fans. As James Kirkup put it in an obituary:

“Flamenco purists deplored his adventurous crossover fusion of flamenco and rock, but they were reluctantly compelled to admit that he was a musical genius who revived the interest of the younger generation in a musical tradition that had been discredited as a symbol of the late dictatorship’s rabid nationalism.”

In spite of controversies he stirred, and the initial lack of success of this album, Camarón remained one of the most famous Spanish performers of his era, and this album has since come to be highly regarded. A comparison to this approach to music on a conceptual level might be Lucio Battisti‘s Anima latina, which has nothing to do with flamenco, but nonetheless, like nuevo flamenco, takes a kind of insular, provincial European music and incorporates international influences (although El Camarón sticks closer to tradition and virtuoso acoustic performance, and features a proud and resilient attitude in place of Battisti’s highly structural existential pondering).