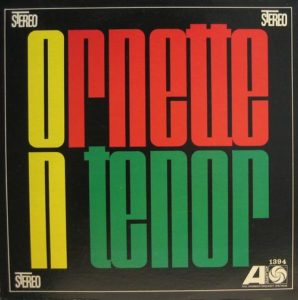

Ornette Coleman – Ornette on Tenor Atlantic 394 (1962)

Often considered the least of Ornette Coleman’s albums for Atlantic Records, those statements need to be put in some kind of context. Even if it is nominally true that this is the least of the Atlantic albums, it is merely the least of one of the most astounding and groundbreaking sets of recordings of the 20th Century. There is still plenty of amazing music to be found on Ornette on Tenor.

The tenor saxophone was Ornette’s primary instrument when he played in R&B and minstrel bands starting in the 1940s. The alto sax became his primary instrument as he committed himself to a solo career making his own music. Using the tenor again here allows Ornette to add some variety to his music, even as his phrasing and musical approach is no different than on alto — save for being a tad slower given the greater volume of breath needed on the tenor. He calls up a few R&B tricks from his past too, like kind of greasy glissando and honking effects, but there still is no mistaking him for any other performer.

“Eos,” and to some extent “Ecars,” which conclude the album, are lesser cuts (“Eos” was the first song recorded in these sessions). These are the only hindrances in an otherwise fantastic album.

Personnel discussions are always of relevance on Coleman recordings, because his musical vision (“harmolodics” he later termed it) was, in many ways, fragile. It depended on assembling a group of performers with shared visions. When he put together bands with performers who were more timid than he was, or just with different ideas, the results were mixed at best. Bassist Charlie Haden had left Coleman’s group, and his immediate replacement Scott LaFaro was later killed in a car accident a few months after these sessions. Jimmy Garrison came on after LaFaro and is featured on these recordings. He had a rocky relationship with Ornette, and frequently rejected Ornette’s musical ideas (he left to join John Coltrane‘s classic quartet, but returned later to record with Ornette in the late 1960s). Garrison is also a more conventional bassist than either Haden or LaFaro. The personal tension surrounding Garrison is evident in places, giving the music a husky aura that Ornette mostly seems to ignore. But even if Garrison holds back by sticking to static motifs rather than diving in headfirst past the point of no return, drummer Ed Blackwell is in peak form here, making the bass playing less critical. His rhythms are slippery and agile. Just when it seems like he’s playing a simple cymbal ride or a march-like beat, he proves otherwise. He never abandons a sense of meter, but he plays without that ever being a limitation. The horn payers, for their part, play with delightful contradiction, with happy-sounding melodies played with much dissonance and irreverence.

While this might be the album to turn to last among Ornette’s recordings for Atlantic (setting aside the many outtake collections, which are still pretty good), it is still well worth investigation for fans of the rest.