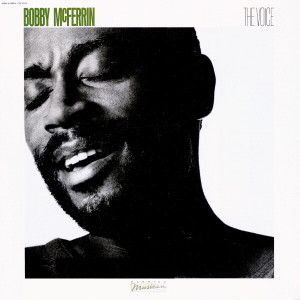

Bobby McFerrin – The Voice Elektra Musician 9 60366-1-E (1984)

Best known for his fluke 1988 mega-hit “Don’t Worry, Be Happy!,” Bobby McFerrin had before that managed to establish himself as a very singular vocalist. He was obviously working from a jazz tradition, of sorts, but he also weaved in a lot of pop sensibilities and pure showmanship.

The Voice was assembled from live recordings made on tour in March of 1984, exclusively featuring unaccompanied vocal performances. In lieu of instrumental accompaniment, McFerrin provides his own assortment of sounds that create the effect or impression of a group performance (without overdubs). He quickly and seamlessly switches between singing words and adding non-syllabic sounds to maintain a syncopated feeling and give the appearance of harmonies that aren’t literally possible from one singer. Key to doing all that was an uncanny ability to make large, sudden, and abrupt leaps in register — not to mention rhythm and cadence — while staying in pitch. And he did all this in a fairly relentless way, using these techniques as the basis for entire songs not just as a brief solo or attention-grabbing interlude (like Sarah Vaughan had done, for example on “They Can’t Take That Away From Me,” by going off-key then back into key). So, on the opener, “Blackbird,” he sings long syncopated, almost scat-like passages in a staccato cadence, then shifts to shifts to shorter, conventionally sung passages (legato), then back again, plus a segment at the end where he simulates a reverb/echo effect. The second track, “The Jump,” uses some of the same techniques, but McFerrin shifts back and forth between the staccato, scat-like, vocal percussion sections, accentuated by slapping his chest rhythmically (both to make additional percussive sounds and to alter his vocalizations) and using overtone singing (throat singing) techniques, and the legato, “conventionally” sung passages almost from word-to-word. By the third song, James Brown‘s “I Feel Good,” he is also prominently shifting vocal registers, from a low growl to a high falsetto. The next song, “I’m My Own Walkman,” a song referencing the still somewhat recent technological invention of a portable audio cassette player. The Walkman cassette player was revolutionary, and, as one source puts it, “It was the privatization and personalization offered by the Walkman that lead to its success.”

But it is worth putting this album in a historical context. Individualism had become a dominant conceptual framework by the mid-1980s. This is to say that there were political overtones to the promotion of individualism and privatization of formerly public goods/values. Discussing the rise and fall of political — and specifically presidential — regimes, Corey Robin has identified the “Reagan Republican regime, which began in 1980” as one that managed to defeat the labor movement (which rose from the New Deal), the Black Freedom movement, and feminism.

An album of solo virtuoso performance (while not unprecedented; see, for example, any number of solo jazz piano albums, or vibraphonist Gary Burton‘s Alone At Last) fit perfectly within such a paradigm, at least in the sense of framing an argument within the parameters of that social and political climate. So McFerrin’s music (and the hit “Don’t Worry, Be Happy!” kind of fits this political program as well), perhaps unintentionally, or at least not consciously, was bound up in the politics of its time. Sonny Sharrock‘s solo Guitar album also deserves mention in the same way.

Feminists have complained about the neoliberal version of female empowerment premised on a few exceptional individuals:

“Because so few women can succeed under current conditions, it is imperative to hold up and valorize the exemplary ones who can. *** But a feminism centered on admirable women also hides the gears that run the social machine. It cannot interrogate the dubious bargains sometimes struck by woman who accrue power in a framework designed by and for wealthy white men. It can only nod approvingly as whatever the ruling class currently requires becomes synonymous with feminism itself.”

It is that same sort of “exceptionalism” that lurks in the background of McFerrin’s album The Voice, the relentless displays of virtuoso singing, which conveniently supports the ruling class narrative that success (or failure) is premised entirely upon individual initiative, and that there are no (or no longer) any structural impediments like racism or sexism or class-base antagonisms worthy of discussion.

If all this seems removed from the music of The Voice, it shouldn’t. There is evidence that this style of music served the ruling class, and that the ruling class recognized as much. When future U.S. President George H.W. Bush (a Republican) used “Don’t Worry, Be Happy!” as his official campaign song for the 1988 election, McFerrin protested (indicating he was a Democrat). Bush, of course, was Reagan’s Vice-President, and a part of the Regan Regime. While there was a time, during the Jim Crow Era, when jazz musicians like Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker could make an (implicit) political statement by demonstrating virtuosity, by the 1980s the sociopolitical backdrop rendered such exercises problematic, in the sense that they no longer supported black liberation, but were congruent with the positions of those opposed to black liberation. Indeed, the largely concert-hall audiences for McFerrin’s performances on this album suggest almost a kind of de-politicized, collaborationist agenda, the sort that led Frantz Fanon to write, “What matters is not so much the color of your skin as the power you serve and the millions you betray.” Black Skin, White Masks. In the coming years McFerrin would sing a version of the theme song to the disgraced comedian Bill Cosby‘s hit TV show, “The Cosby Show,” and Cosby was somewhat notorious for advocating a neoliberal form of multiculturalism that preached personal responsibility as both the necessary and sufficient causal factors for the material circumstances of poor minorities. He also would go on to work for a Chamber Orchestra, the sort of organization that is a haven for the rich and self-styled aristocrats (and wanna-bes).

If all this makes McFerrin’s music seem problematic, it should only do so in a certain context. The music itself, heard in a proverbial vacuum, is wonderful. But its success was due, in part, to its proximity to the dictates of the ruling ideology of the day. Sonny Sharrock’s album Guitar had, on its surface, all the same traits: individual solo performance (albeit with overdubs), virtuoso technique, etc. But Sharrock went for a completely different tone. His album had a dreamy, almost mystically searching quality, with a pervasive sense of hopefulness and longing. McFerrin’s The Voice, in contrast, features songs that mostly trade in hedonistic pursuits, and the occasional retro triumphalism (his use of James Brown’s “I Feel Good” is both a dose of hedonism and an assertion that the civil rights movement is over and was won, not an ongoing struggle or even mostly a loss). Take also Rahzel, the hip-hop vocalist/beatboxer who kind of took McFerrin’s vocal approach a step further (just check out “If Your Mother Only Knew”), but who also made music that was far less compatible with mainstream tastes (and ruling ideology), due to his focus on the characteristics of a more lower-class lifestyle.

So, The Voice deserves a place among the finest jazz albums of its decade. Yet, it should also be consciously associated with the conservative (centrist [neo]liberal) strain of jazz music of the time (ref. Wynton Marsalis). That shouldn’t take away from what it achieves in purely artistic terms, but it should contextualize those achievements, and, more importantly, explain McFerrin’s success as being dependent upon much more than the purely artistic elements of this album or his other work.