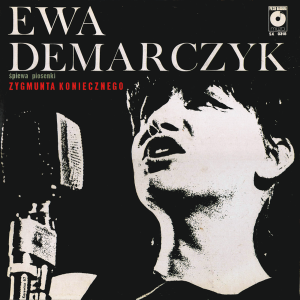

Ewa Demarczyk – Ewa Demarczyk śpiewa piosenki Zygmunta Koniecznego Polskie Nagrania Muza SXL 0318 (1967)

Frequently compared with Édith Piaf, it seems like a better comparison for Ewa Demarczyk’s singing is somewhere between the sing-speak folk/pop style of chanson à texte singers like Jacques Brel (especially his most dour songs like “Amsterdam” and “Ne me quitte pas”) and the scrappy, punky cabaret theater music of Lotte Lenya — this album reminded me of one of my favorites, Lotte Lenya Singt Kurt Weill. The emphasis is on dramatic recitations of poetry, set to dark, almost minimalist orchestrations. Demarczyk was part of the group of performers at the Piwnica pod Baranami (Cellar Under the Rams) theater in Kraków, Poland. She was nicknamed “The dark angel.”

This album was a big success in Poland. Demarczyk would gain further international renown as a recording artist in the 1970s, when she worked with the Soviet state-owned record label Melodiya (remember that at this time Poland was part of the Soviet Eastern Bloc). While her later albums sold better, thanks to better distribution and promotional support from the Soviet government, it was this, her debut full-length album, that seems to garner the most critical praise, even decades later.

It is interesting to place this album in the context of the Brezhnev era as well as in the continuum of periphery/core tensions in cultural production. Many reviews, particularly from Poland, describe this album and Demarczyk’s work more generally as being uniquely Polish. Around the same time, the Brazilian tropicalists were engaged in a similar sort of debate about their work and its cultural significance on an international scale. In Brazil, there was a clear tension between the irreverent kitsch of the tropicalists and the rigid literalism of the nationalists. Many of Demarczyk’s supporters tend to fall prey to nationalist chauvinism, or at least their descriptions belie a desperation in trying to break out of the orbit of Western cultural dominance. Much like fellow Piwnica pod Baranami performer Krzysztof Komeda, whose work drew heavily from that of Miles Davis, Demarczyk’s work had obvious precedents. Unlike the tropicalists, though, it is harder to see how her music presented any sort of radically new formulation, as opposed to being (merely) excellent performances that subtly expanded existing forms within their established paradigms.

As to the Brezhnev angle, it might be said that this is a Stalinist work. Now, immediately, this claim will probably draw some concerns. Isn’t Demarczyk work part of a “dissident” tradition? Well, yes, but that is precisely what makes it Stalinist. After the so-called Khrushchev Thaw, Brezhnev re-introduced a more Stalinist line. There was a resurgence of Stalinist thought. “Wiersze Baczyńskiego” is a good example of an attempt to find confirmation of meaning in life:

“Only take out of these my eyes

the painful glass mirror — image of days

which roll white skulls

through burning meadows of blood.

Only alter this crippled age,

cover the graves with the river’s robe,

wipe from hair the battle dust,

The black dust

of these angry years.”

Here it is useful to ask whether Demarczyk’s music more closely resembles the writings of Andrei Platonov or Mikhail Bulgakov. While she does modulate her voice across a range that must be characterized as singing, her nearly monotone recitations of poetical texts emphasize a “protest” attitude. That is what Bulgakov did, and Stalin called him up once to talk — Stalin was known to do this, and to hang up the phone mid-conversation when asked to validate the other speaker’s concerns. The question is whether artists have internalized the Stalinist ethos and self-police themselves to advance the regime, or whether they look toward something else. Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita has been described as being an expression of Stalinism rather than — as is commonly assumed — a critique of Stalinism. It is kind of a form of hero-worship, a belief in some sort of dynamic actor who can break out of constraints on behalf of others.

Platonov, in contrast, developed a more ambiguous stance toward the Soviet government. He recycled the standard government lines in a kitschy way that ridiculed the perverse aims of the political sloganeering as betrayals of socialist ideals. One reviewer has described his writing as being rich with examples of musical, elegant prose while also embracing the crude, the dirty, the obscene. In his novella Happy Moscow, the protagonist Moscow Chestnova is a parachutist (a glamorous occupation at the time) who suffers an accident while building the Moscow subway, then aligns herself with the most hopeless and destitute of the city. The novella comments on how the socialist revolution leaves intact certain inequalities and vestiges of class, while emphasizing how existential concerns about finding meaning in life proceed in parallel and quite separate from the material concerns of creating socialism in one country. The challenge is how to find meaning in the increasingly unprecedented realities of modernity.

Zygmunt Konieczny provides the orchestral music here, which is always respectful. Eastern Bloc countries had ridiculously easy access to symphonies and classical music performers. It was a type of music largely supported by communist governments. The use here of orchestral accompaniment is entirely respectful and deferential. There is really nothing ironic or cynical about it. The backing music is performed earnestly and literally. The textual recitations, however, often stand in contrast. Because of the use of a lone individual standing against the force and weight of the orchestra, the “dissident” attitude is felt most strongly. At the same time, the use of ornate orchestral accompaniment belies a kind of sophistication. Demarczyk forged her performing career out of a collegiate environment, centered around the oldest medical school in Poland. This is clearly a kind of elitist music. It isn’t about solidarity or the triumph of the workers, or any sort of other kind of socialist realism. This is about individual grandstanding in the name of The People. This is Stalinism! And the censors were pretty smart. This music got past them precisely because it is line with Soviet politics of the time.

In a way, think of this music as the Polish equivalent of the urban folk movement in the United States, and the bourgeois chanson of Western Europe. It is pretty good. It revels in the same sort of quest for individual recognition through showy, ostentatious performance nominally disguised as being for a larger cause.