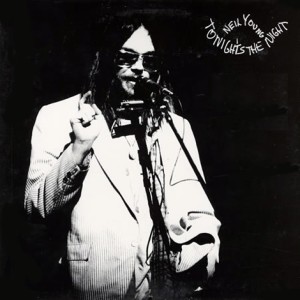

Neil Young – Tonight’s the Night Reprise MS 2221 (1975)

Neil Young was among the most interesting rock artists of the 1970s. Aside from his landmark After the Gold Rush, and the commercially successful Harvest, he made his so-called “ditch trilogy” (or “doom trilogy” or “gloom trilogy”) of albums: Time Fades Away, On the Beach, and Tonight’s the Night. Unlike the other two albums, though, Tonight’s the Night is not melancholic or rancorous but ominously morose. Yet it is also cathartic. It isn’t music for a sunny day or a party with friends. It is for solitary, late night introspection.

Young had fired Crazy Horse guitarist Danny Whitten in late 1972 just before a tour, due to drug abuse limiting Whitten’s performance. Shortly after, Whitten died of an overdose. Then a few months later former Crosby, Stills Nash & Young roadie Bruce Berry died of an overdose too. The standard narrative is that Young’s “ditch trilogy” was his reaction to Whitten and Berry’s deaths, and his feelings of responsibility and complicity. That seems fair enough. Yet Young’s music of this period is lasting because it captures more than just coping with Whitten and Berry’s deaths. This music is also about the death of the countercultural project of the 1960s.

Tonight’s the Night has some resemblances to John Lennon and Harry Nilsson‘s infamous “Lost Weekend” escapades. It has the feel of being caught at daybreak after a full night of partying. The album stumbles about, a bit angry, disenchanted, heartbroken, unsure, drugged-out. It is about coming to terms with the “loss” of Whitten and the 60s project, but also getting out all the feelings that engenders and then getting past it all to get ready for something else. In this way, Young’s reaction to the situation of the early/mid 70s was to not give up on what had happened before, coast into comfortable (and forgettable) soft rock that sort of fit commercial expectations from the sorts of institutions that really crushed the 60s experiment. Promoter Bill Graham lamented how the old rock scene died when acts became more interested in money than music. Young cut against all that.

Young has better individual songs elsewhere, but for pure mood Tonight’s the Night is a a killer. This is a “warts and all” sort of affair. The songs are sloppy, because Young didn’t want his band to be too familiar with the material prior to recording, and that is a drawback for some. Still, the reason this matters is that Young stubbornly stuck with 60s idealism even after those forces had, by late 1973 (when most of the album was recorded), conclusively lost, and the era of the Powell Memorandum had begun. Young didn’t pretend that the 60s project was still alive and well, nor did he capitulate and join the reactionary counter-revolution. He affirmed what was good all along in the 60s project — and the spirit of what Danny Whitten and Bruce Berry’s lives represented — that sought something outside the established, rigid and oppressive rules of the early post-war period, while grimly accepting its limitations and failures. William Davies wrote that

“from the Enlightenment through to the present . . . unhappiness becomes a basis to challenge the status quo. Understanding the strains and pains that work, hierarchy, financial pressures and inequality place upon human well-being is a first step to challenging those things. This emancipatory spirit flips swiftly into a conservative one, once the same body of evidence is used as a basis to judge the behavior and mentality of people, rather than the structure of power.”

Neil Young is one of rock music’s shining examples of somebody who resisted the “flip” to the conservative side of all this. He kept tilting against the establishment. “Roll Another Number (For the Road)” encapsulates that feeling best, with a calm acceptance and determination, soildering on, moving past the escapism of “Mellow My Mind” with a buddy stoner charm, only to have the hopes that “Roll Another Number” implies evaporate with the existential road trip narrative “Albuquerque.”

As reviewer BradL wrote, echoing Dave Marsh in Rolling Stone, “there’s not a touch of self-indulgence on the record because Young is as honest and hard on himself as anyone else. He doesn’t want your pity, nor even your forgiveness[.]” On “Speakin’ Out” he calls himself a fool, on “World on a String” and “Borrowed Tune” he finds no meaning or significance in being at the top of the music business. So let’s appreciate Young’s unhappy, depressing music like Tonight’s the Night for all it stands for: an attempt at something better than the status quo.

There are plenty of bluesy classic rock riffs. The second half has more conventionally catchy classic rock. But, hell, even the archival live performance from 1970 with Whitten (adding vocals) on side one, “Come on Baby Let’s Go Downtown,” manages to be a rousing affirmation of what the entire album sets out to do. Still, in spite of the anthemic charge of many of the melodies, the band is loose, imprecise.

“Tonight’s the night [duh-da–dah—duh___]

Tonight’s the night”

The significance of chanting these vacant lines on the first version of the title song, traded against some briefly tinkling piano and a bass line that rises and then suddenly falls, are a challenge: to figure out what tonight is the night for. It is the struggle for meaning that gives this music its power. If the 60s project failed, and Whitten and Berry died, how can Young, or anybody else, carry on the core ideals of what it and they proposed without failing, without being snuffed out? What makes Tonight’s the Night one of Young’s finest moments, is that it denies any sort of assurance that there is an answer to that question. No one knows — sure as hell not Young. But he rattles the cage of his own mind, and puts that on record for the world to hear, trying to take some kind of step forward on terms that he himself sets.